Jennifer Howard’s plan to raise up a struggling federal NDP in Election 2019

The campaign manager’s task: find a way for Jagmeet Singh and the New Democrats, stuck for years in a distant third in the polls, to vault from underdogs to overachievers

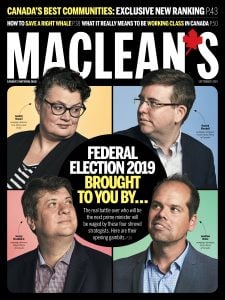

Jennifer Howard (Photograph by Jessica Deeks)

Share

Jennifer Howard’s third day as NDP Leader Jagmeet Singh’s chief of staff fell on Dec. 6, the national day of remembrance and action on violence against women. The timing was notable. Twenty-nine years earlier, the École Polytechnique massacre was what first spurred Howard to jump into politics.

Back then, she was a student at Brandon University, finding her way in Manitoba’s second city. Now, after making a name for herself as an adviser to former premier Gary Doer and eventually a senior cabinet minister in Manitoba, Howard is the NDP’s federal campaign director. Her task: find a way for Singh and the New Democrats, stuck for years in a distant third in the polls, to vault from underdogs to overachievers.

The relatively inexperienced team around its fledgling leader needs all the help it can get.

Howard’s new life in federal politics began with the exit of Willy Blomme, a former Jack Layton speech writer and Broadbent Institute director who’d helped the left-leaning Valérie Plante win Montreal’s mayoralty and then joined Singh’s team as chief of staff in January 2018. Ten months later, Blomme was out for “personal reasons,” and Singh’s office had a glaring hole at the top of its org chart.

As an interim measure, Singh hired party stalwart Michael Balagus, a former chief of staff to two Manitoba premiers and a veteran of NDP campaigns stretching back to the ’80s, as his right hand. In mid-November, Singh announced Howard as Blomme’s permanent replacement, playing up her experience as a cabinet minister and an executive director of the Women’s Health Clinic in Winnipeg. She started Dec. 4. In May, Singh appointed Howard the party’s campaign director, with Balagus, whose day job is Ontario NDP leader Andrea Horwath’s chief of staff, as special adviser.

LIBERALS: Meet Jeremy Broadhurst, the Liberal campaign manager

CONSERVATIVES: Meet Hamish Marshall, Conservative campaign manager

GREENS: Meet Jonathan Dickie, Green Party campaign manager

When Howard walked into work on that first day as chief of staff, the party was mired in sagging morale. Singh had been party leader for more than a year but hadn’t yet won a seat in the House of Commons. The NDP had stalled below 15 per cent in popular support. And the party’s fundraising machine was sputtering: Conservatives had raised $7.4 million in the last quarter of 2018 and Liberals had raked in $6.4 million. New Democrats managed just shy of $2 million, slightly ahead of a resurgent Green party which raised a record $1.5 million. There were quiet murmurs that Singh wasn’t up to the job.

“We were nine months out from an election, and we frankly needed somebody who could take the position from a standing start and get the job done. There was no time for a learning curve,” says Kathleen Monk, a principal at Earnscliffe Strategy Group who worked for Layton and watches the party closely. “Job one was ensuring that Jagmeet got elected.”

When Prime Minister Justin Trudeau called a by-election in Burnaby South and Singh threw his hat into the ring, the contest was a must-win. “If he didn’t win, there was already talk, from the fall through to the winter, about dire consequences,” says Monk, hinting at rumblings that Singh would get the boot. “Major columnists in the press gallery were writing stories betting against him.”

Singh won handily, beating Liberal challenger Richard Lee by 12 points, and was in Parliament. Job one, done. Howard tells Maclean’s she also wanted to instill a sense of routine amidst the chaos of Ottawa’s political bubble. “Very quickly you can feel like you’re just chasing things all day long,” she says. “I wanted to make sure we had some strong systems in place so that we were able to deal with those issues as they came up.”

Howard’s former colleagues in Manitoba describe a friend and mentor who earned a reputation as a calm, level-headed thinker through three terms in government and who managed to survive some bare-knuckle brawls without many enemies.

Howard’s first campaign was a stinker. She ran for the NDP in the 1997 federal election, carrying the banner in her hometown of Brandon. She won 13 per cent of the vote, finishing a distant fourth. Not that it was unexpected. “Nobody led me astray. That was going to be the likely outcome,” she tells Maclean’s. “But it was what convinced me I wanted to make electoral politics part of my life.”

Ten years later, after a move to Winnipeg and stints working as a women’s health advocate and an adviser to Doer on health care issues, Howard ran again. This time, she won with 46 per cent of the vote, and the prize was a seat in Manitoba’s legislature.

By 2009, then-premier Greg Selinger appointed Howard, who endorsed his leadership bid earlier that year, to cabinet as minister of labour and immigration. She was promoted to House leader in 2012, when she also served as minister of family services and labour. The next year, she scored the ultimate promotion—to finance minister. A year after that, she quit cabinet with four colleagues after they lost faith in Selinger’s leadership—but failed to convince the premier to step down. Erin Selby, the minister of health who was another member of the “Gang of Five,” says Howard commanded respect at cabinet. Whenever an issue was hashed out around the table, she says, “you were waiting to see where Jennifer stood.” When conversations grew heated, Howard stepped in. “Jennifer has often told me her role is to be the calm when the storm is swirling,” says Selby. “She can speak logically when emotions are running high and is always very good at lowering the temperature emotionally in the room.”

Andrew Swan, the House leader when he joined Howard and Selby in stepping down, says Howard “played a particularly important role in the effort” to privately persuade Selinger he should resign. Swan describes a fiercely loyal party foot soldier. “The overriding factor was her loyalty to the party,” he says. “The duty to your party is above and beyond the duty to any one particular person.”

In 2016, just months before the campaign that ultimately dumped Selinger’s NDP from power, Howard was nominated and ready to run for re-election. But she stunned political observers by abruptly abandoning those ambitions. Instead she packed up with her wife, Tara Peel, and their two kids and moved to the nation’s capital, closer to Peel’s family and far from the political fights inside the provincial party.

In Ottawa, Howard took up a gig as executive director of the Public Service Alliance of Canada, the biggest union of federal workers, as thousands of its members were mired in payroll hell, either underpaid, overpaid or not paid at all, thanks to the infamous Phoenix debacle. Two years later, the federal party came calling.

Since May, Howard and Balagus have focused on the fall campaign. They worked closely together over most of the Doer and Selinger years. Monk says their partnership bodes well. “What gives me hope about this campaign is the fact that Balagus and Howard have worked together over a number of years, know each other’s style, can support and challenge one another,” she says.

Swan partly attributes the NDP’s winning streak in Manitoba to strict message discipline: picking a couple of issues and sticking to them. He credits Howard’s strategic mind for some of that success. “Jennifer has always been really gifted at crafting, but also delivering, those messages,” he says.

Singh’s inexperience on a national campaign is coupled with a second frustration: many Canadian voters don’t really know what he stands for. But the party is convinced he’s likeable. “We know that people don’t know much about him,” says Monk. “When they have the opportunity to meet him, talk to him or see him, they like him.” To make up ground, he’ll need to focus on affordability issues: “jobs and job creation, pharmacare and health care, policy ideas that are the core of New Democratic strength,” says Monk, who adds that Singh’s likeability draws a sharp contrast to Andrew Scheer and Trudeau.

By July, eight months into Howard’s run as chief of staff, the party remained solidly in third place (and even fourth in the occasional poll). Its second-quarter fundraising was still dismal: $1,433,476 from 14,936 donors, a fraction of the Tories’ $8.5 million haul from more than 50,000 Canadians—and behind even the Greens, who raised about $4,000 more than the New Democrats.* Eleven NDP incumbents, one-quarter of the party’s caucus, aren’t running for re-election. And Singh remains untested on a gruelling campaign.

“Being an underdog is not new for the NDP,” says Howard. After all, the provincial party surprised its critics almost every time Doer or Selinger won re-election. Monk, a veteran of the NDP’s orange wave in 2011, repeats the edict that campaigns matter. “I know and have seen too many times how dramatically things can change in a campaign,” she says. “I have a lot of faith in this team being ready to execute in September.”

Howard expected to finish fourth in 1997, running as a no-hope candidate in her hometown. Now, even as the NDP struggles to make up ground against its well-funded rivals, the party still believes it can overachieve—and hopes that Howard’s calm prairie pragmatism is the ticket to an upset.

Update: This story has been updated to reflect fundraising totals from the second quarter of 2019.

This article appears in print in the September 2019 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “The reinforcer.” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.