What is Maxime Bernier and his People’s Party selling?

Is it going to be that government’s too big, Canadian values are besieged, or that elitist politicians are out-of-touch? No option looks promising.

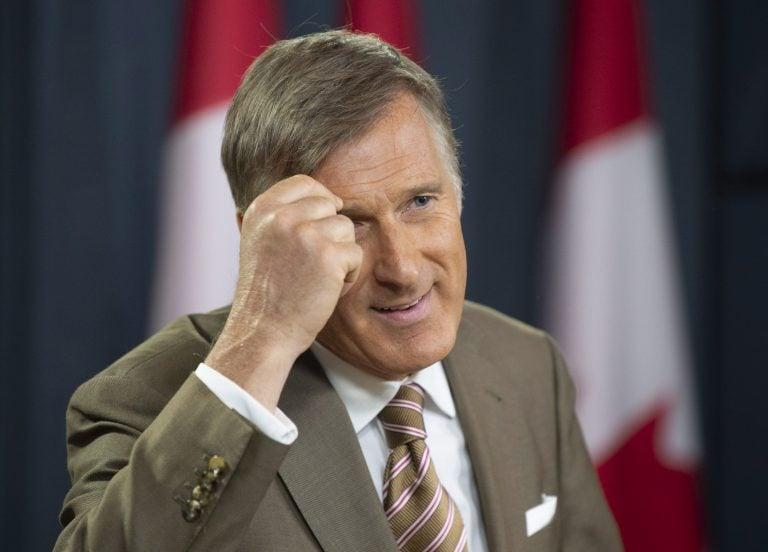

Maxime Bernier speaks about his new political party during a news conference in Ottawa on Friday, Sept. 14, 2018. (THE CANADIAN PRESS/Adrian Wyld)

Share

There’s a lot about Maxime Bernier’s new People’s Party of Canada that’s hard to take seriously, starting with that name. Still, the Quebec MP’s news conference today to launch the thing offered moments of real interest for anyone trying to sort out what’s happening these days on the right side of the political spectrum.

Start by listening to how Bernier, in what should have stood out as the beating heart of his statement at the National Press Theatre, tried to frame his populist purpose. This looks a little wordy, admittedly, and starts out like boilerplate, but it’s worth reading to the end:

“For too long Canadian politics has been hijacked by interest groups, cartels, lobbies, international organizations, corporate or union interests, and the interests of politicians and bureaucrats in Ottawa who are disconnected from ordinary citizens. This is why government never stops growing.”

Plenty of conservative-minded Canadians will hear nothing wrong, and lots right, with Bernier’s summing up of what’s wrong with Ottawa. But here’s the problem, if you think about his conclusion: government that seems to never stop growing hasn’t been a factor for a long time now.

The total federal tax haul stood at 14.5 per cent of Gross Domestic Product in 2001, but had slipped to 12 per cent of GDP last year. Overall federal spending amounted to more than 20 per cent of that broadest measure of the economy from the mid-1970s to the mid-1990s. By last year, though, spending as a per cent of GDP stood at 15.5 per cent.

READ MORE: How should Andrew Scheer talk to Canadians?

So the notion that unending government sprawl is the problem—perpetuated by left-liberals in collusion with pocket-lining special-interests—hasn’t held water for many years. In fact, back in 2003, Stephen Harper, then an opposition leader pondering how to reinvigorate the Canadian right, made the point that his adversaries on the left had learned key lessons during the Margaret Thatcher-Ronald Reagan era of the 1980s. “Socialists and liberals,” Harper said, “began to stand for balanced budgeting, the superiority of markets, welfare reversal, free trade and some privatization.”

And that sustained change in the mindset of the centre-left has made it much harder today for someone like, say, Conservative Leader Andrew Scheer to differentiate his brand. Free trade? Scheer would like nothing better than to be seen as its natural champion on the national stage. But Prime Minister Justin Trudeau made finalizing the trade deal with Europe a top early priority, and presently, as everybody knows, his government is consumed with trying to salvage NAFTA.

But what about the role of government, especially as it relates to families? That used to serve up a nice, crisp partisan and ideological dividing live. As recently as the late stages of the Jean Chrétien-Paul Martin era, for instance, Liberals advocated bigger government daycare programs, while Conservatives called for direct support payments to parents. Indeed, Harper delivered just that after he won power.

But then the Trudeau Liberals ran for election in 2015 on the Canada Child Benefit—an expanded, streamlined program of even bigger federal cheques sent right to parents. Having implemented the CCB soon after forming government, the Liberals now tirelessly tout it as their signature accomplishment. So much for what was once a defining Liberal-Conservative point of contrast.

There are many examples like these. It’s not that there is no remaining room for Conservatives to stake out policy turf that shows voters an attractive alternative to the Liberals on the role and size of government. It’s just that doing so requires far more nuance, and less bracing bluster, than Bernier and other populists generally care to try to deliver.

READ MORE: What Andrew Scheer told Conservatives after Maxime Bernier’s exit

And that leads them to test more treacherous paths. Often this means what’s generally referred to as “identity politics.” Thus, Bernier talks a lot about the problem of migrants crossing the border from the U.S. into Quebec. He frets about sustaining Canadian values. “I’m not saying that people who come today don’t share Canadian values,” he told reporters today. “I want to be sure that people who come in the future, they will always share Canadian values.”

Does that sound oddly tentative, more than a little evasive? His caution is entirely understandable. After all, playing identity cards has proven to be risky. Harper was hurt badly at the polls by the backlash against his talk of banning niqabs from citizenship ceremonies, and setting up barbaric practice tip lines, and what have you, in the 2015 campaign.

So Bernier’s claim that ever bigger government is the problem is outdated. His attempts to tap into anxiety over immigration leave him talking so vaguely that he risks undermining his claim to being a rare political straight-shooter. That leaves him with neither a big case against big government, nor a coherent identity-politics pitch.

What’s left? Well, he is firmly against the supply management system that protects milk, egg and poultry farmers. He’s also for ending federal health transfer payments to provinces that allow Ottawa to insist on universal health care. He’s for a much flatter, simpler tax code. These are the sorts of specific proposals that might make sense for any right-of-centre political leader. But they are decidedly not the readymade stuff of populist slogans. For that, ever-worsening government bloat and some sort of immigration crisis would be handy.

Inconveniently, however, Canadian government, by historic measures and international standards, isn’t bloated. And the story of Canadian immigration, despite the current border issues, is overwhelmingly about newcomers integrating well and contributing mightily. The challenge for Scheer—if he’s picking up on those serious flaws in Bernier’s sales job—is to find a way to be compelling without pretending such fundamental problems exist when they really don’t.

Go back to Bernier’s mission statement. Before he gets to the line about ever-growing government, he talks of “politicians and bureaucrats in Ottawa who are disconnected from ordinary citizens.” Now, this suggests a tack always available to conservatives of a certain sort. Not spurious claims about out-of-control government. Not odious allusions to values and identity. Instead, a politics based simply on being more relatable, more in touch.

If Bernier sees potential there, he’s not alone. Scheer’s main speech at the recent Tory convention in Halifax was mostly about portraying himself as the ordinary-guy alternative to a Prime Minister who grew up rich and famous. It’s not at all clear that Canadian voters are primed just yet to trade glamorous for garden-variety. But packaging the intangibles of their leader’s life story at least doesn’t force Conservatives to lapse into the stale Big Government critiques of yesteryear or, worse, wade into the contemporary sludge of identity politics.

This obviously isn’t where Bernier meant to lead us today. But, looked at this way, the messages he tested in launching the People’s Party can only leave us hoping that next year’s federal election isn’t waged over the size of government or, far worse, the values of Canadians.

Against those dispiriting possibilities, the prospect of an old-fashioned, superficial contest about the contrasting personas of the Tory and Liberal leaders looks positively reassuring.