How to fix our roller-coaster economy

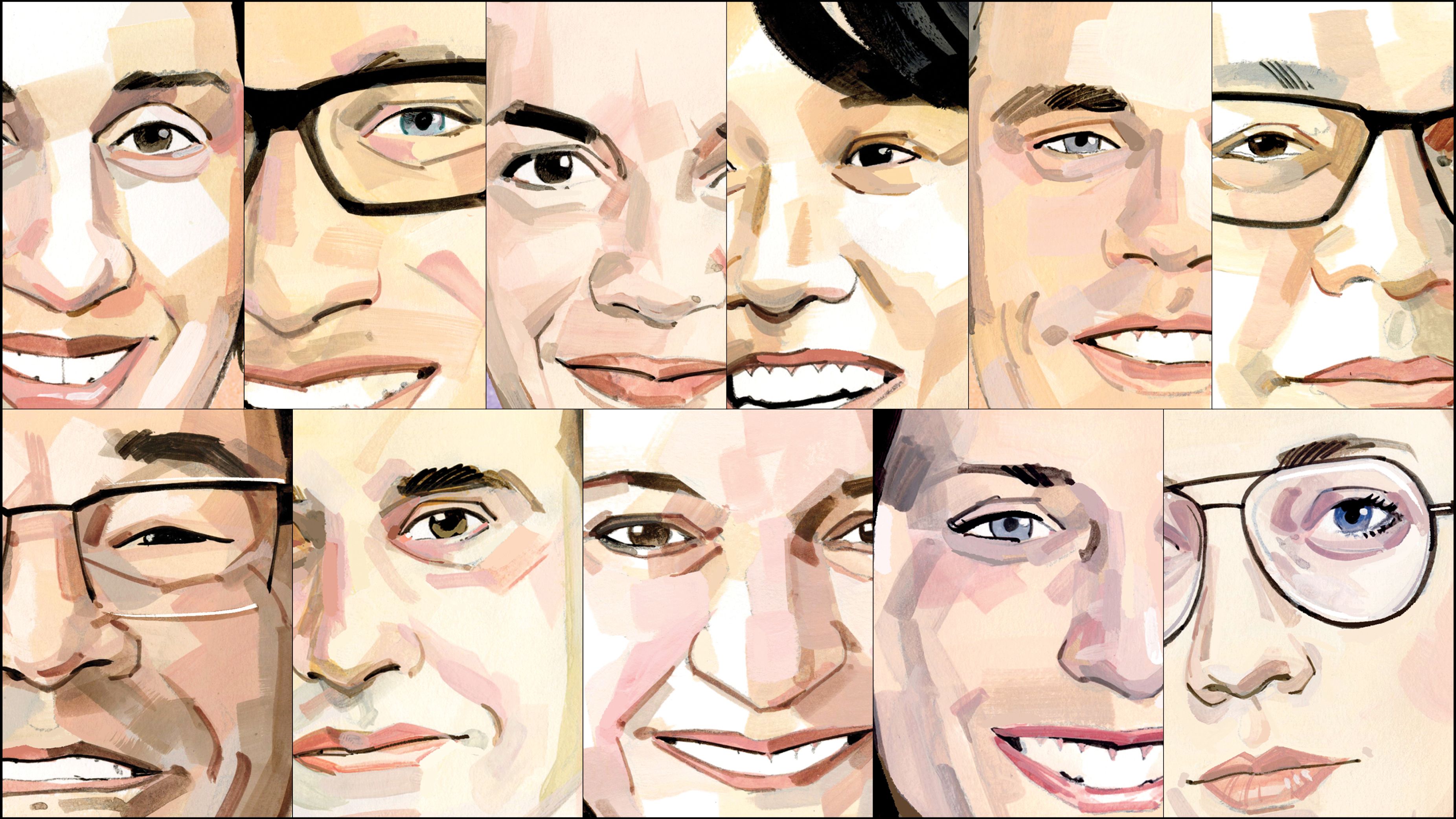

Ballooning inflation, mounting debt, a labour shortage—and have you seen gas prices? Here, the country’s smartest economic minds explain how Canada got so financially wild, and how to make things better.

Share

August 11, 2022

At some point in the last couple of years, the word “unprecedented” had been used so often that it lost all of its potency. First it referred to wave after wave of the coronavirus that upended supply chains and our very way of life. Now, it applies to every cranny of the Canadian economy. In February, financial analysts were left breathless as the country’s annual inflation rate surpassed five per cent for the first time in more than 30 years. Then, spurred by runaway gas prices, along came another jump: in May, Canada’s inflation rate hit 7.7 per cent. In June, 8.1. Again: wow.

This economic turbulence is old news to anyone who has recently tried to buy groceries, get a car, fuel up their car or do virtually anything involving money. Now overheard in Canada: “Since when does an Ubered dinner for two cost $65?”; “Why can’t I find anyone to hire in a country of 31 million?”; and “Where the heck are all the rental cars?”

The central question, though, is how everything got to be so fiscally wacky, seemingly all at once—and how to make it all better. In the following pages, a team of the country’s smartest economic thinkers and industry experts examine some of Canada’s current hot spots and, where possible, offer their two cents on how to transform them.

WHAT’S WITH THESE INTEREST RATES?

BY JEAN-PAUL LAM

Canada isn’t just experiencing high inflation; it’s experiencing persistent and volatile inflation, at levels we haven’t witnessed in almost 40 years. A pandemic plus supply constraints plus excess demand—plus a labour shortage? Economically, it’s a perfect storm. With its rapid-fire interest rate increases, the Bank of Canada is trying to cool things down.

How rent prices got so high

BY MIKE MOFFATT

Senior director of policy and innovation, Smart Prosperity Institute

When the pandemic kicked off, rental-housing prices fell by five to six per cent in most Canadian provinces. But that brief reprieve has ended: as of May, the average monthly rate for all vacant units in Canada hovered around $1,900, marking a 10 per cent increase from just a year ago. To fix Canada’s rental market woes, the government will have to get shovels in the ground. A vacancy tax could help, too.

How climate change is costing us

BY CAROLINE LEE

Senior research associate, Canadian Climate Institute

Governments and corporations have largely cast climate change as an environmental issue. Many individual Canadians think the same way. They’re still not connecting the rising cost of living to climate change, but evidence of this link is everywhere. By 2025, Canadians could lose an average of $700 from their annual household income due to climate change–related factors alone.

Why delivery apps are dying

BY VASS BEDNAR

Executive director, master of public policy in digital society, McMaster University

Consumers—particularly young, busy urbanites—have become increasingly dependent on companies like Uber for transportation, takeout, and delivery of essentials like medicine and clothing directly to their homes and workplaces. This market has always been built on a shaky foundation, but in the wake of the pandemic, on-demand apps are struggling.

How’d we get into so much debt?

BY KARYNE CHARBONNEAU

Executive director and senior economist, CIBC Capital Markets

In recent months, inflation has further tightened Canadians’ margins, raising the price of the everyday essentials. As a consequence, credit-card debt, which was decreasing during the pandemic, is now on the way up again. Between the expensive housing market and the rising cost of living, some people can’t weather the storm.

Why food is so pricey

BY GISÈLE YASMEEN

Senior fellow, School of Public Policy and Global Affairs, University of British Columbia

Canadians are paying nearly 10 per cent more for groceries—rice, pasta, meat and more—than they did in 2021. But when food is consistently treated as a market-driven commodity, you inevitably get the kinds of price volatility that Canadians are seeing at the moment. Access to food should be treated as a right, not a purchasing decision.

What to know about student debt

BY ERIKA SHAKER

Director, national office, Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives

The total amount of student loans owed to the federal government surpassed $22.3 billion in 2020. This figure is alarming, but it doesn’t even include provincial and personal loans, lines of credit and education-related credit-card debt. Loans and grants help, but a better idea would be to cancel existing debts and eliminate tuition fees entirely.

Where did all the rental cars go?

BY CRAIG HIROTA

Vice-president of government relations and member services, Associated Canadian Car Rental Operators

When stay-at-home orders went into effect two years ago, the travel industry came to a standstill. Demand for rental cars went down to virtually zero and operators were forced to sell off huge chunks of their fleets. This so-called “carpocalypse” is the result of the same supply-chain issues that are affecting everybody right now.

Why crypto went kaboom

BY RYAN CLEMENTS

Assistant professor and chair in business law and regulation, University of Calgary

About 14 per cent of Canadians hold some crypto. The crash we saw this year—during which the crypto economy lost US$2 trillion in mere months—is partly because, in the midst of an already rocky economy, people are selling off crypto as the riskiest asset in their portfolio. What the sector needs is more regulation.

Seriously, these gas prices?

BY JAN GORSKI

Program director, oil and gas, Pembina Institute

Canadians were preoccupied with the prices at the pump well before this year’s sticker shock. Our current prices have less to do with domestic policy than with global costs of oil and gas, but policy can still help manage the crisis in the long term—starting with a federal electric-vehicle mandate.

How the labour shortage got so bad

BY ARMINE YALNIZYAN

Economist and Atkinson Fellow on the future of workers

Never in Canada’s history have we seen labour numbers like this. At the start of this year, there were just 1.2 unemployed people for every job opening, and we hit an all-time high of one million vacancies in March. Shifting demographics are the driving forces.