Getting through the pandemic one Archie comic at a time

Jillian Horton: Every night at bedtime my son and I read Archie. Amid the brutal COVID disruptions, I feel viscerally what he is drawn to: the containment of it all.

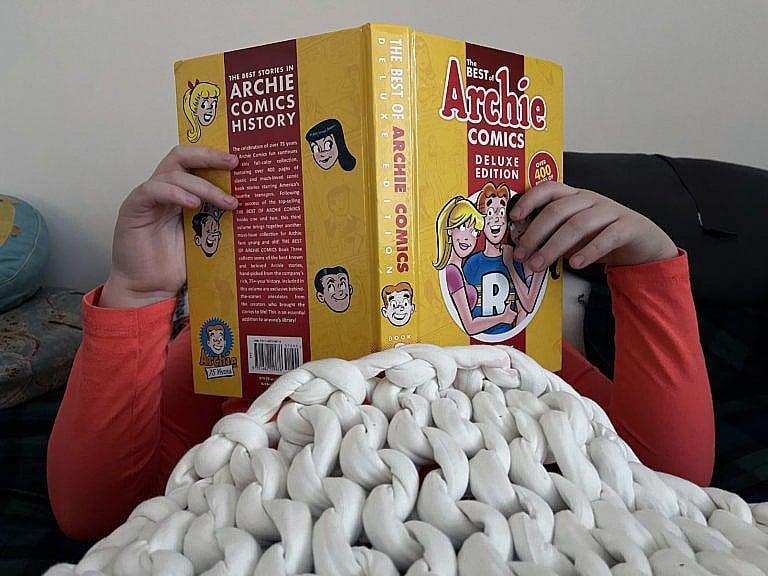

(Courtesy of Jillian Horton)

Share

With this week’s announcement of school deferrals and the dreaded flip back to online learning, our children’s education is brutally disrupted once more. My three sons have all struggled with the impact of closures and our general failure to make schools safe. But my youngest son has coped with that stress by spending hours every day at a school he doesn’t actually attend. It’s called Riverdale High. And you might even know the famous red-headed kid he hangs out with.

When classes first shuttered in 2020, I’d prod him. “Archie is fine, but want to read something else?” I offered the classics of my youth: the beautifully illustrated Adventures of Babar. Tom’s Midnight Garden. The Passage to Narnia. He’d always respond with the same, pleasant “No, thanks,” and turn his attention back to Jughead and Arch.

Now I happen to think that comics are classics too. As a kid, they were a staple in my family, but for a very specific reason. My sister loved comics. Twelve years my senior, she was left profoundly disabled by a brain tumor when she was six years old, and my parents were desperate to fill her life with whatever small things gave her pleasure. Every few weeks, we went to a tiny news-and-smoke shop, where the smell of fresh paper mingled with tobacco. With my sister trailing me in her wheelchair, we’d make a beeline for the perfectly-stacked pile of Archie’s Digests at the very back. We’d peruse the options, debating the merits of Betty and Me vs. Jughead’s Jokes, until we agreed on the final selections. Then, we went home to lose ourselves totally in Archie’s world.

My favourite thing about that world was probably the most obvious: no one in Riverdale had real problems, like a sister in a wheelchair whose life had been destroyed by a brain tumor. And no one in Riverdale seemed worried about their parents’ mental health or even mortality in general—subjects that weighed on me constantly in a family where we did not take those things for granted.

I know there are problems with Archie and the gang. Arch is a lothario. He, Betty and Veronica are heavily triangulated. Jughead has an eating disorder. Reggie would score highly on a sociopathy scale. Moose is the kind of guy who grows up to have several restraining orders against him.

And yet, I feel viscerally what my son is drawn to: the containment of it all. There are no pandemics, no persisting existential threats. Nobody ever holds a grudge that goes beyond a storyline. There are only so many permutations of what can go wrong in Archie’s universe.

I have a stable income and lots of privilege, and so my son has been shielded from COVID’s worst indirect impacts on kids. The things he’s lost are still sad and painful—time with cherished grandparents, two years of playtime with friends, holiday gatherings, and the little moments that loom large in the highlight reel of our childhood. But I don’t believe his losses will hold him back in life, and I can’t say the same thing for millions of kids around the world. We have failed those children, and the scope of what they have suffered will take us years to grasp. I’m inclined to think that whatever healthy coping strategies they have used to get through it should not be tampered with.

So now, my son and I have a ritual: Every night at bedtime, we read Archie. We take turns voicing the characters and we usually end up laughing so hard that one of us wakes up the dog. I briefly forget about the smoldering crises at our hospitals, the tailspin precipitated by Omicron, my deep misgivings about whether governments are doing enough to keep our kids safe. For a few minutes, all of that goes on pause. Archie has become a nightly respite for me, too.

Someday, maybe Archie and Reggie will have a showdown about whether masks are required to set foot in Pop’s. Maybe Dilton will find himself patiently explaining to Moose for the hundredth time that vaccines don’t contain fetal cells and he hasn’t been magnetized. Maybe Betty will tell Ronnie she has to cancel her huge Saturday night party, that she’s being selfish by only thinking about herself when Riverdale’s test positivity exceeds 30 per cent.

But for now, Riverdale is free of the endless problems that have infiltrated every aspect of our daily lives. That’s why I’m letting my kid stay in that world whenever he wants, until I know there is something better for him to come back to.