As teens learn their rights, they’re defending them—and winning

Teen rights used to be, in effect, whatever their parents dictated. But Millennials and Generation Z have pushed back, and the balance of power is shifting

Brett Gorski at McGill University

Share

Ron Felsen had been a teacher since 1998 and a vice-principal for five years when he got the top job at Northern Secondary School in tony north Toronto. The new principal—who already had at least 10 proms under his belt—was hardly inexperienced. A month later, he was presiding over the Halloween dance when he decided to shut it down one hour in. “We’re not talking about one or two kids drunk,” he says. “We’re talking about a cafeteria full of kids falling over on each other.”

To combat the culture of drinking, Felsen asked police to deliver a school-wide presentation on safe partying—to no avail. Six times in three years Felsen had to remove inebriated students from school dances, sending them home or even to the hospital to have their stomachs pumped. Eventually he cancelled all senior dances save the prom, a milestone often marked by much pomp and excess. He was already at his wit’s end when sharply dressed students spilled out of limos and filed into the hall’s front doors for 2013’s end-of-year dance. Once again he had to call the parents of one extremely intoxicated girl who was slurring her words and staggering around. The next year, he held her up as an example to the student council as he pressed his case for a Breathalyzer at the prom-dance door as a last resort.

The council argued against it, but after Felsen discovered at least one school in each of Ontario’s 32 English school boards used them before prom, he pitched the idea to the parent council and they bought it. “They know their kids and they know their kids’ friends,” he says. “They hear stories.” Two days before tickets went on sale for the 2014 dance, Felsen announced that, from now on, entry to the prom would require a ticket—and a breath test.

Student council vice-president Simon Gillies was incredulous. “Is this legal?” he asked president Brett Gorski. Other students were equally enraged; one put up posters depicting Felsen with the Orwellian caption, “Big Brother is watching you.” As heads of the student council, Gorski and Gillies figured it was up to them to fight back.

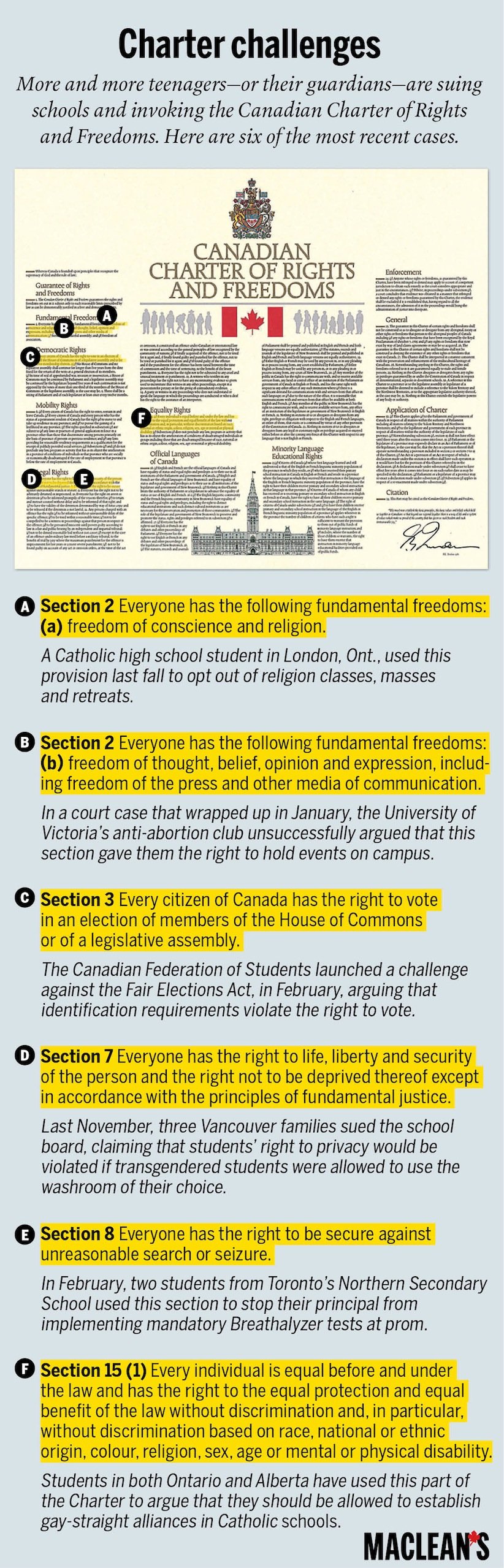

Gillies swiftly started doing his own research. He found Section 8 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms—protection from unreasonable search and seizure—and a Toronto District School Board policy that warned against unreasonable grounds for search and seizure. At the recommendation of his father, a lawyer, Gillies contacted the Canadian Civil Liberties Association, which quickly lent its support to a lawsuit—quashing Gillies’s worries that they might dismiss council as “just a bunch of whiny kids” fighting for the right to party. They connected the students with Jonathan Lisus, a Toronto lawyer willing to work the case for free. “They basically knew what the issues were,” says Lisus, who filed a Charter challenge against the school board. “They just needed help procedurally advancing them.”

Despite meetings and letters, Felsen—who had sought his own legal advice—wouldn’t budge. As the two sides waited for a court date, they made an interim agreement: there would be no Breathalyzers at the 2014 prom. Before the dance, Gorski and Gillies held a meeting for all Grade 12 students. “We worked for this,” Gorski told them. “Let’s do it right.” Three hundred and ninety people attended prom. Not one was reprimanded or removed for underage drinking.

Related: Teen girls take over the world

Since then, a 17-year-old successfully sued her landlord for refusing to rent her a Toronto apartment. Last October, a Catholic high school student in London, Ont., used the Charter’s freedom-of-religion provision to get an exemption from mandatory religion class. The next month, three Vancouver families filed a lawsuit against their school board for allowing transgendered students into the washroom of their choosing, claiming it violated other children’s right to privacy.

Then there was the strip search. In late February, a 15-year-old high school student in Quebec City was caught sending a text message to a friend that said “Do you want pot?”—a running joke in a school that had seen a string of recent locker searches. The principal and vice-principal interrogated the girl, whom they suspected of selling drugs, for an hour and a half before the two female staff members asked her to strip behind a curtain so they could search her clothes for drugs. She did, but they found nothing. Now the family is planning to sue for damages in the Superior Court of Quebec. “Everybody has the right to privacy, and that’s a bit lowered at school because it’s a student and you need to manage them,” says François-David Bernier, the lawyer representing the family. “But they made a big mistake.”

Teenagers used to be second-class citizens whose rights were, in effect, whatever their parents decided they were. And kids, for the most part, accepted that. But, like all teenagers who have challenged authority, Millennials and Generation Z have started pushing back and the balance of power is shifting. “Young people today are much smarter and more aware of their rights than may be fashionable to admit,” says Sukanya Pillay, executive director and general counsel for the civil liberties group that helped with the Breathalyzer case. “They’re not taking things lying down. They’re not just going to accept whatever’s prescribed to them.” Kids these days know their rights, and, for better or worse, they’re defending them. And winning.

The cultural shift started in 1979, the year Pink Floyd released The Wall, the seminal rock opera that featured the hit single Another Brick in the Wall (Part 2). In one section of the song, a chorus of children belts out the line that’s been repeated, with gusto, by millions of kids, millions of times since: “Hey! Teachers! Leave them kids alone!”

With that refrain, the English prog-rockers tapped into the zeitgeist of their day. The United Nations had declared 1979 the International Year of the Child, which “really created an excitement,” says David Morley, president and CEO of Unicef Canada, who remembers watching people march through the streets in Brazil in support. Though it may have had more significance in the developing world, where exploitation, health care and education were a concern, Canada wasn’t immune from its effect. For one, the Children’s Aid Foundation was established to support the most vulnerable children in society: those in the child-welfare system. “That year fundamentally changed the way the world thought about the rights of children,” says Morley.

Read More: Your teenager’s scary brain

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the first part of a new Constitution, was signed into law in 1982. Two years later, the Young Offenders Act established a separate justice system for children between the ages of 12 and 17, recognizing that they did not have the same moral, intellectual or emotional maturity as adults. The 1990 Convention on the Rights of the Child, the UN’s most widely ratified treaty, recognized “that childhood is entitled to special care and assistance.” A decade later, after a Charter challenge to Section 43 of the Criminal Code, which permits spanking, the Supreme Court of Canada set out new boundaries on the use of disciplinary force against children. Today, students learn about the Charter as early as Grade 5 and again in new courses like the mandatory half-credit civics class introduced in Ontario in 2000.

Young people, on the cusp of adulthood and itching to assert their independence, have always had a don’t-come-into-my-room kind of attitude that hearkens back to James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause, says Pillay. But today’s youth have grown up in a wildly different environment than previous generations. “We always hear about how kids don’t understand privacy rights because they’re ceding their privacy with social media and Facebook.” But Pillay sees Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat as a testing ground where kids are introduced to the concept of rights by trial and error—who can see what they post, whom they can block and whom they can delete from their online lives.

Today’s cohort of teens is the first to grow up almost entirely in a digital, post-9/11 world. Because of their technological sophistication, they can witness and participate in conversations about rights, whether the topic is invasive anti-terror legislation or WikiLeaks and government secrecy. “We’re facing mass state surveillance,” Pillay says. “There’s a trickle-down effect. In schools, administrations are taking a more heavy-handed approach to the students. But the students, exercising their democratic rights, are saying, ‘Wait, that’s not right.’ ”

Zakaria Abdulle has witnessed the transformation. Since graduating from high school, the 24-year-old University of Toronto student has worked on a handful of human rights issues with youth, including the Policing Literacy Initiative, which connects police to diverse communities to improve service. “We see it everyday. Young people are like, ‘Hold up. We may be young, but we don’t feel we should be treated a certain way because of our age. We feel like our voices matter.’ ” He hopes the groundswell of awareness closes the gap between young people and often-inaccessible disciplines like law, especially among underprivileged kids and teens who don’t have an equal opportunity to exercise their rights. “Parents that are working two or three jobs,” he points out, “they don’t have time to advocate.”

Parents are still the gatekeepers for their kids’ rights because, until they’re 18 or 19, depending on the province, kids can only launch lawsuits through a litigation guardian. That’s usually an adult, but, in the case of emancipation—where a minor is an adult in the eyes of the law—young people can act on their own. Last March in New Jersey, a teen who moved out of home sued her parents for child support; the 18-year-old asked for $654 a week, plus money for legal fees and tuition. The emancipation was contested, but she eventually abandoned the lawsuit and moved back home, only to receive a $56,000 scholarship from a New England university. Then, in December, another New Jersey student, a 21-year-old who lives with her grandparents, successfully sued her divorced parents for nearly $17,000. In a blog post called “The age of entitlement,” her mother describes her daughter as a hard-drinking, rebellious runaway who managed to spin the law to her advantage. “She doesn’t want a family; she wants money,” her mother wrote. “And the courts have told her that this is completely acceptable.”

Never have young people had so much power, but most don’t grasp the need for great responsibility. Michele Peterson-Badali, an Ontario Institute for Studies in Education psychologist who specializes in children’s rights, says there’s a gap between young people’s awareness of their rights and their understanding of what it entails: the responsibility to respect the rights of others. “They might think they’re savvy and act like they’re savvy, but they’re not,” she says. “Even at 16 . . . few kids will understand that rights are a bounded entitlement. I can’t do whatever I want. I can’t say things that are hateful. I can’t hurt somebody.” And that’s what throws adults into an uproar: if they’re still the same old irresponsible, mischievous and occasionally nefarious kids, why hand them so much power? “There tends to be a gut reaction on the part of adults to feel threatened by the idea—‘these kids, they have too many rights,’ ” says Peterson-Badali. “I think that’s a misconception.” The trick, she says, is to ensure kids properly appreciate what rights really mean.

These days, they’re learning much of what they know from television and YouTube videos. “We’ve interviewed thousands of children, and I haven’t met one who knew their rights,” says Katherine Covell, co-founder of the Cape Breton University Children’s Rights Centre. The centre developed a curriculum that incorporates rights-based case studies and role-play exercises and shopped it around to schools, but Canadian educators weren’t interested. “If you’re going to respect the rights of the child, you have to listen to them and give them opportunities to express their opinions,” Covell says. “A lot of teachers were wary of that.” British schools, meanwhile, embraced the program and saw a drastic transformation over its 10-year implementation: bullying all but disappeared, discipline issues dwindled and children performed better academically. “You can’t just have Rights Week or Rights Day,” Covell explains. “It’s not a quick fix.”

Along with the recent swell in cases involving children’s rights, there have been abuses. Children, exercising their new-found power, can subvert the laws to serve their own malicious, if not criminal, purposes.

It was April 2012 when Ontario teacher Susan Dowell learned this the hard way. When the Grade 4 students walked into their music class at a school north of Toronto to find Dowell was the substitute for their regular teacher, they immediately started horsing around and putting her patience to the test. “I’ve been doing this for 15 years. My intuition told me to nip that in the bud,” says Dowell, 52, who was a real estate agent before she switched careers. She sent four kids to the office. After the bell, Dowell moved on to cafeteria duty—or, as she describes it, “being thrown into a pack of wolves.” As she watched over the screaming, food-flinging masses, a boy walked by and tossed an uneaten banana into the trash. “You don’t throw perfectly good food out,” she told him. “Take it home or eat it or save it for after school.” He took the banana out of the garbage, peeled it, took one bite and threw it back in. By the end of the day, Dowell had decided she wouldn’t substitute teach at the school ever again, but it was too late.

The following week, she was dismissed from another job because students at the previous school complained that she had used excessive force on some and publicly humiliated another. She drove home in a daze. Her union told her to wait on word from the Children’s Aid Society, whom the vice-principal had called to sort out the matter. In the meantime, she wasn’t allowed to step on school property or talk to other teachers. “I had no support,” she says. “No one to talk to.” Eventually, she learned that the boy with the banana had told his parents Dowell made him eat from the garbage. She says the parents complained to the vice-principal, who interviewed the troublemakers sent to the office; they said she’d grabbed one of the girls by the neck. According to Dowell, no one asked for her account.

It was a month before Children’s Aid cleared Dowell’s case, allowing her to return to work. The events had shaken her, though, and tarnished her reputation. Kids and colleagues treated her differently, she says. The accusing child and parent, however, faced no consequences. Dowell’s union told her that this was the “new normal”—she would have to grin and bear it.

She did—for a while. Last year, while on a long-term placement she thought would finally lead to a steady teaching position, Dowell was accused of scratching a student. She was off work for three weeks. Again, the case was dropped. To this day, she doesn’t know who complained.

“Kids just have no idea of the ramifications of what they’re saying or the power they have,” she says. There have always been—and there will always be—bratty kids, but today’s parents are raising increasingly entitled children, she says. In her eyes, it’s become an us-versus-them battle, and young people now have the advantage. “When did that switch happen?” she asks. “I would correlate it entirely with when children began to understand that they had rights.”

In 2012, a B.C. student launched an elaborate accusation of sexual assault against her teacher, lifting scenes from a TV show to describe his actions and creating a fake diary as evidence. Most cases are kept quiet, and false accusations aren’t recorded, so no official statistics exist. But a 2010 Nipissing University study about a shortage of male teachers showed 13 per cent of 223 male Ontario teachers surveyed had been falsely suspected of inappropriate behaviour. School boards, says McGill University associate professor Jon Bradley, who has spent years studying false accusations, don’t have basic policies to deal with an allegation, such as consulting all involved parties and explaining to accusers the implications of a false allegation. “It’s innocent until proven guilty. If a teacher is guilty, they can hang from a lamppost,” says Bradley. “But we need procedures.” Even in an era when kids can and do sue adults, they can do just as much damage without any legal action at all.

Nine months after the 2014 Northern Secondary School prom, Ontario’s Superior Court ruled in favour of Brett Gorski and Simon Gillies, deciding that mandatory Breathalyzer tests violated their constitutional right to freedom from unreasonable search and seizure. The two teens were relieved—and proud. “I hear in my classes, ‘Don’t ever put anything you did in high school on your resumé,’ ” says Gorski, now a business management student at McGill. But you’ll find the case on her CV; taking the school board to court taught her more than any law course could. “It was interesting that two 18-year-olds, fresh out of high school, were able to make an impact,” says Gorski, who intends to continue being an advocate for social justice. “When I talk to Grade 9s, they think it’s exciting that they can stand up for their rights. It’s kind of foreign to take a principal to court.”

Now principal Felsen has a most pressing concern: with the 2015 prom about three months away, how does he prevent the usual bacchanal? “It does tie our hands a bit,” he says of the court’s decision. Parents expect him to put on a prom year after year, but he, like other administrators, is running out of tools to combat underage drinking. Because of the decision, Malvern Collegiate in east Toronto, which has used the Breathalyzer on students for years, will stop using the test, and dozens of other schools will likely follow suit. Felsen wouldn’t be surprised if high schools decide to get out of the prom business altogether, even though he knows that would cause even more of an uproar than the Breathalyzer did, given their social status as a rite of passage.

He does see one upside, though. “I think it’s a great civics lesson,” he says. “We teach kids about rights and responsibilities, so here’s a great lesson about how decisions are made and what you do about decisions you’re not happy with. We have appeal measures and all sorts of different things we as adults do, and certainly kids should know they have that ability as well.” He’s heartened by Gillies and Gorski, who were professional and polite throughout the case. As for future students, “I’m confident that kids will do the right thing,” he says. “If I didn’t have confidence in kids, I wouldn’t be a school principal.”