My uncle was affable, charming and well-read. But the losses at Normandy tormented him.

‘For years, he kept records of platoon members he knew had survived the war. When the new phone book came out, he would check to see if they were still alive. But he never contacted them.’

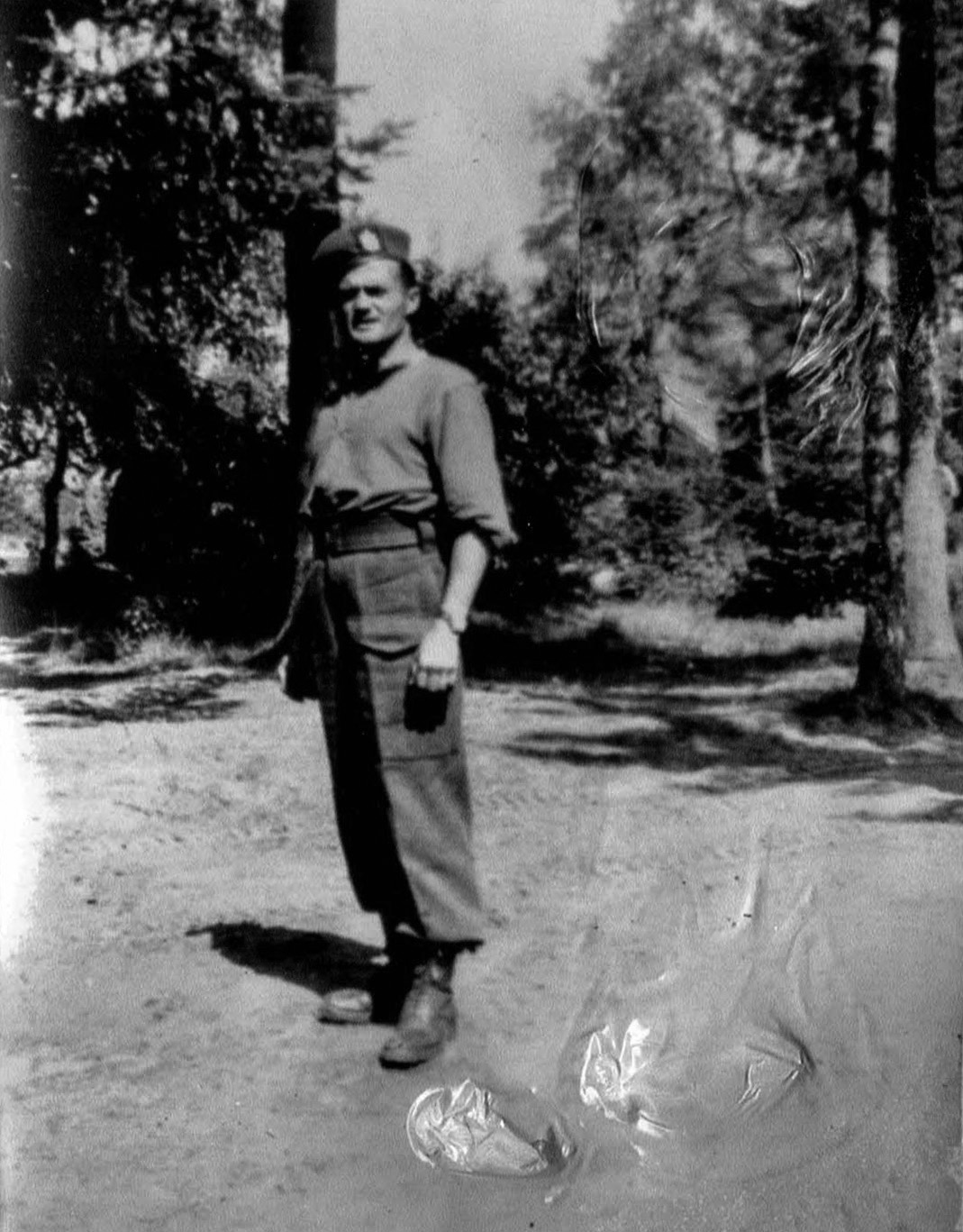

Pat Bennell, first from the left, in Amersfoort, Netherlands (Courtesy of Irene Martin)

Share

My uncle was a World War II veteran who lived into his 90s. He was involved in the Normandy invasion during D-Day, and in the liberation of Holland. When the war was over, he moved to Toronto. While he always presented a smiling, affable personality, he was never really close to anybody except his two brothers, one of whom was my father. Pat was reclusive and had no friends or emotional attachments. We now recognize that he was probably experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder, but neither my brother nor I knew that term when we were growing up. In those days there was very little knowledge of or treatment for this illness. To us, he was just our Uncle Pat, and we loved him.

RELATED: When Canada finally started to remember World War II

He was intelligent, well-read, and charming. After World War II, he lived in a succession of Toronto rooming houses. Lodgings consisted of a bedroom on the second or third floor of an old house, a hot-plate for cooking, and a bathroom down the hall. He was the ideal tenant—clean, quiet, paid his rent on time and didn’t want pets. He went to work every day in an upholstery shop. He came to our family’s place, also in Toronto, for Christmas, Easter and an occasional Sunday dinner. He never brought a romantic partner. He never phoned. When I married and moved to the U.S., I wrote him the occasional letter, usually about big events, such as the arrival of our daughters. His only correspondence was an annual Christmas card, always sent in response to mine. After he died, I found every note and card I had ever sent him, carefully wrapped up in a bundle and saved for decades. How I wish I had sent more!

When he first developed Alzheimer’s disease, my brother became his legal guardian. Eventually, when Pat was no longer able to care for himself, he went into a nursing home. He was in his eighties at the time. I visited Toronto and went with my brother to see him. Uncle Pat was smiling, cheerful and charming until my brother asked him about D-Day. A look of horror came over his face. “That was a bad time,” he said, and then was silent. We never asked again. But when we were clearing out his room at the last boarding house, we found notes that he had made about the war. They helped us piece together his experience and its profound effect on his identity.

He was born Patrick Bennell on May 30, 1912, in Henley, England, and came to Canada in 1921, moving with his mother and brothers to Winnipeg. He enlisted in the army on July 22, 1941, in Toronto. He was a rifleman and signalman in the Queen’s Own Rifles. He shipped to England in 1941 on the SS Pasteur, returning to Canada in 1945 on the Monarch of Bermuda. He received an honourable discharge on Feb. 13, 1946.

On June 6, 1944, 7 a.m., the Queen’s Own Rifles landed at Bernières-sur-mer as the right assault battalion of the 3rd Canadian Division, and suffered heavy losses. Pat occasionally spoke of his experience in Normandy when we were growing up. He described how he and several of his platoon members took refuge in a stone building that was hit by armour-piercing shells. We have the impression he was the only one who survived, though I cannot verify this notion. Being a radio-signalman, he was a marked man, as destroying the communications ability of the enemy was a priority for the opposing forces. I remember him saying that “church steeples didn’t last long in Normandy,” as they were useful for both sides for surveillance purposes and were destroyed for that reason. At one time, he confided to my brother that he had killed people during the war, and it was clear that that memory horrified him.

RELATED: Real postcards from the First World War that survived a century

The losses at Normandy tormented him. He believed that an accurate account of what happened there had not been told, and that the death toll had been minimized. Notes he scrawled in the margins of various books about D-Day questioned the accuracy of the casualty lists. After he died, my brother and I found two letters in his belongings. Apparently he long planned to write to the editors of various newspapers to set the record straight, and actually drafted two letters, but never managed to send them.

He also listed the place names of all the towns and villages he went through in Europe, places that the Canadian Army slogged through, foot by foot. When we were children, Uncle Pat spoke on a number of occasions about wintering in Holland, where trenches filled with water almost as fast as one dug them. “The coldest winter of my life,” he said, a remarkable observation from a man who had sold newspapers as a child on the corner of Portage and Main in Winnipeg, well known as the coldest corner in Canada.

For years, my uncle kept records of platoon members he knew had survived the war and were still alive. Each year, when the new Toronto phone book came out, he would check to see if they were still there. But he never contacted the other survivors. When I first visited him in the nursing home, I asked him if there was anything I could bring him. He thought briefly and then, smiling, requested a phone book. I believe he wanted the security of knowing there were people still alive who had not died at Normandy. People whom he could contact, but never would. All those deaths somehow froze his heart and destroyed his capacity to trust and form other relationships.

I used to think of Alzheimer’s disease as an unmitigated evil, but when my uncle developed it, I was not so sure. Alzheimer’s put him in a wheelchair. He forgot how to eat. He didn’t know me or my brother anymore. He stopped using the phone book to track his comrades. He could no longer carry on a conversation. But he at last forgot the Normandy invasion. Those of us who loved him can only be thankful. He died on Jan. 25, 2004.

Irene Martin lives in Skamokawa, Washington, and is a writer specializing in local and regional history.