Project Consent gets straight to the point

A new campaign that went viral last week aims to strip away the metaphors from lessons on sexual consent

(Project Consent/Youtube)

Share

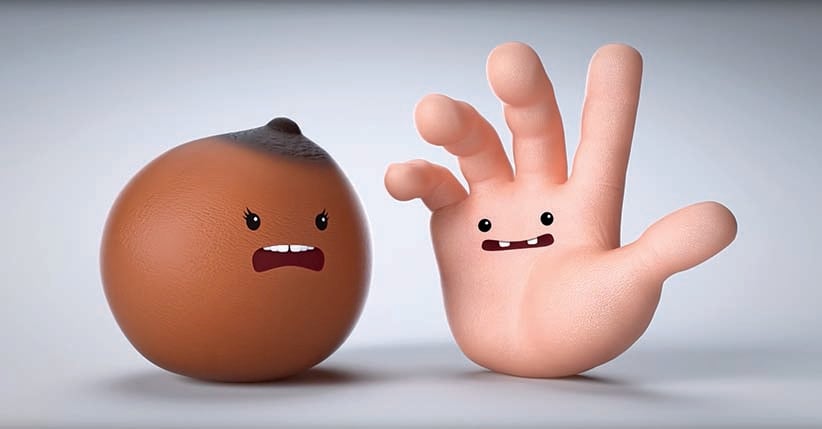

A hand grabs a breast; the breast says “whoa, no,” and the hand backs off. “Consent is simple,” reads the slogan at the end of the video, one of three 20-second animated clips that went viral last week amid the buzz of International Women’s Day. The videos, released by a not-for-profit called Project Consent, uses talking body parts to explain sexual consent bluntly.

“We really wanted to get straight to the point,” says Mackenzie Cakebread, a University of Toronto student and one of three staff members at Project Consent. “You don’t need to glam it up.”

The clips, which garnered more than five million views in their first five days, have only one message: no means no. “There’s one with a vagina and a penis, [one with] a butt and a penis, and a hand and a breast,” explains Cakebread. “One of the body parts will go too far, and the other one will go, ‘No, I’m not into this.’ The other one will go, ‘Okay,’ and sort of walk away.” Terry Drummond, chief creative officer at Juniper Park, a Toronto-based marketing studio, which offered the idea for the videos pro bono, reiterates that the goal is simplicity. “There’s nothing as direct as body parts,” he says.

Project Consent’s approach offers a contrast to the abundance of campaigns that explain sexual consent using metaphors. Most famously, a video released last fall equates sexual consent to accepting a cup of tea, a public service ad based on the idea of British blogger Emmeline May. “Tea Consent” suggests that people must agree to sex in the way they agree to drink a cup of tea, without physical compulsion. They’re allowed to change their minds after consenting to sex, just as they might have second thoughts about a serving of orange pekoe while waiting for a kettle to boil. The video takes the analogy further: “If someone said yes to tea, started drinking it, then passed out before they finished it, don’t keep on pouring it down their throat. Unconscious people don’t want tea.”

From Tea Consent came a wave of offshoots. Internationally, the video was translated into accepting jollof rice in Nigeria and shaved ice in Hawaii. In Ontario, Western University’s sexual education committee released a campaign called “Cycling through Consent.” “Being dressed in bike shorts and a helmet doesn’t automatically mean someone wants to ride a bike,” it offers. “It’s quite presumptuous to think they do . . . you don’t toss them up on a bike and say, ‘Oh come on, it’ll be fun.’ ” Even if they agree, they’re allowed to change their minds by “back-pedalling.” And, of course, “unconscious people can’t ride bikes.”

The creative approaches hope to break the ice on an oft-taboo topic. Two in three Canadians don’t understand that sexual consent must be both positive (silence doesn’t suffice) and ongoing, according to a 2015 survey of 1,500 people by the Canadian Women’s Foundation. One in 10 didn’t understand that consent is required even with a spouse, and one in five mistook “sexting” for consent to physical sex. “I think analogy helps us remove the politics from something more complicated,” Emmeline May says. Marc Nuot, a volunteer at ConsentEd, an Alberta-based not-for-profit, agrees. “We let a lot of stuff fly because it’s difficult to talk about,” he says. “Metaphors are very helpful.”

Tea was not the first or last analogy used. In a 2012 TED talk titled “Sex needs a new metaphor,” American sex educator Al Vernacchio proposes the comparison of eating pizza. “Before you have pizza with somebody, you have a conversation about it and you talk about what people like,” he tells Maclean’s. One of Vernacchio’s high school students suggested the analogy of making an ice cream sundae, which requires people to agree on flavours, toppings, and the vessel of a cone or cup. “I thought that had a lot of cool potential,” says Vernacchio. Other proposed comparisons include getting a tattoo (the artist should stop if the client falls asleep), borrowing a cellphone (permission to make a call doesn’t mean permission to search through personal messages), and watching Pulp Fiction (people may change their minds midway through the movie). In response to the tea video of 2015, Banksy, the graffiti artist, tweeted out a cartoon that offered three other analogies for consent: eating breakfast, in which eggs should be optional; playing poker (nobody should be forced to gamble); and weightlifting (wearing a muscle shirt doesn’t imply a desire to lug around someone else’s dumbbells).

The team at Project Consent agrees metaphors can be good conversation-starters, but argues that the true meaning of consent can get lost in such analogies. “It’s not about that,” says Cakebread. “It’s about your genitals, and how you have a right to choose what you do with them.” She commends Western University’s effort to talk about consent, but, “Why would you use biking as a metaphor?” she wonders. “It’s a very different kind of activity.” Likewise, she saw comments online asking, “What does pouring tea on someone’s lap have to do with someone grabbing me in a club?” She says, “Most people want someone to just say it directly. It’s not going to be a tea situation.”

Although school curricula often include direct discussions of sexual consent, the lessons are not as memorable as the Pixar-meets-penises style of Project Consent’s videos. For example, Ontario’s sexual education curriculum, implemented in February 2015, requires that Grade 8 students explain that “consent is communicated, not assumed. You can ask your partner simple questions to be sure that they want to continue: ‘Do you want to do this?’ or ‘Do you want to stop?’ A ‘no’ at any stage does not need further explanation.”

Of course, anyone who watches three snappy clips of talking body parts will need further explanation to grasp the full, legal meaning of consent as defined by two subsections of the Criminal Code. The age of consent varies with the age gap between the people involved, and it also takes into account mistaken age, and factors such as the parties being married, or if one party occupies a position of authority or trust. “Nobody understands that from watching a cup-of-tea video,” says Dan Chivers, an Edmonton lawyer specializing in sexual assault cases.

Then there are the emotional nuances of consent. Betty Martin, a sexuality coach for couples in Seattle, says truly consensual sex entails not just permission but rather equal desire, and she warns, “many people resist saying what they want to do because they think it spoils the mood.” And Marc Nuot of ConsentEd says people should stop focusing on the definition of consent and rather address the need to honour decisions. “It has always been not so much a failure to understand consent but a failure to respect it,” he says.

While Project Consent hopes to expand its campaign to explore the complexities in a direct way, metaphors that try to do the same can end up making the issue doubly confusing. One bewildering offshoot of the Tea Consent video, called “Tea, it’s a bad idea!” attempts to highlight the difficulty of proving consent. It warns that the police department’s “tea special investigation unit” can charge people with “forcible tea,” and the video exaggerates the need for pre-consent by suggesting tea-makers should get their tea-drinkers to sign forms. Alternatively, upon request, “three UN peacekeepers and a videographer will be sent to observe.”

In defence of metaphors, May and Vernacchio argue that analogies make sex easier to talk about, and clearer to understand. May admits no single analogy can perfectly explain consent; “some people will try to use those flaws to discredit the entire analogy,” she says. Vernacchio, who also teaches English, says, “We think in metaphor. Metaphor is really helpful in helping people hold onto complex ideas.” Before deciding on pizza as the metaphor, Vernacchio considered a staircase or ladder. “I honestly don’t know when I hit on pizza,” he says, “but I knew when I hit on it, I thought, ‘This is it; this is the one.’ ”

For Project Consent, the animated body parts campaign is “the one.” The organization has quardrupled its Twitter following, and the videos have swept through the United States. “It was a really a home pride sort of moment,” says Cakebread. Juniper Park’s regular clients include CIBC (it designed the mascot, Percy the Penguin), along with Kraft and the Source, and Drummond is confident that these companies won’t mind being associated with a studio that publicizes naked body parts. “I can’t imagine anybody objecting to a campaign that promotes a better world,” he says. “We’re in Canada. We’re not a backward country. I have good faith in people that they’ll understand it the way it’s intended.”

Project Consent did run into one problem: Instagram deleted its account because of the graphics. “It’s not anticipating that a cause is going to come along and use nudity in a powerful way,” says Drummond. Cakebread is working to restore the account, explaining that the campaign offers an alternative to the murky conversations that came before, which she can’t help but describe by using a metaphor herself. As she says, “it was all sort of beating around the bush.”