The strange and wonderful world of microbes

The Earth Microbiome Project aims to catalogue all the microbes that live on the planet

Share

Kate Lunau is covering the 2012 annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Vancouver, a gathering of some of the world’s finest brains and celebrities of science. On Feb. 16-20, Lunau will bring you a sneak peak of the latest research and findings, posting to Macleans.ca on anything from healthcare and climate change, to food security, and more. Follow Kate on Twitter:@Katelunau, #AAAS, #AAASmtg.

Kate Lunau is covering the 2012 annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Vancouver, a gathering of some of the world’s finest brains and celebrities of science. On Feb. 16-20, Lunau will bring you a sneak peak of the latest research and findings, posting to Macleans.ca on anything from healthcare and climate change, to food security, and more. Follow Kate on Twitter:@Katelunau, #AAAS, #AAASmtg.

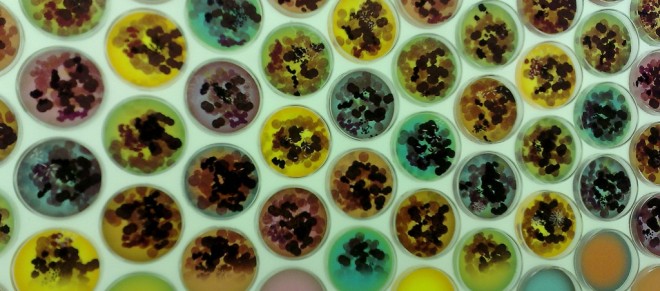

Leonardo da Vinci said that we know more about the stars in the sky than what lives in the soil, scientist Janet Jansson pointed out Friday, and apparently that’s still true. She and a few colleagues gave a briefing in the afternoon about the Earth Microbiome Project, which aims to catalogue all the microbes that live on the planet—what Jansson called “Earth’s dark matter,” because they’re all around us but so little is known about them. It’s an ambitious effort, since there are more microbes in one tiny cup of soil than there are stars in our galaxy, she pointed out while holding up a plastic glass full of dirt.

Their session ended up being one of the liveliest of the day: as she and other researchers spoke about the bacteria they study, an assistant toured the room, collecting swabs of everyone’s cellphone and shoes to test them and see what they could find (I personally had mixed feelings about finding out what sorts of germs populate my iPhone, since I’ve been attached to it all day to tweet about the conference). Bacteria can be found up to 3 km deep in the Earth, and six or seven miles in the air, collaborator Jack Gilbert said: they are literally all around us, and they are most definitely all over my phone.

They’re on us and inside of us, too, outnumbering the human cells in our body ten-to-one: as the moderator said, in what are becoming his characteristic zingers, we’re all basically “walking apartment buildings for microbes.” It sounds disgusting, but they play a crucial role in regulating our health—and if we can find the right ones, scientists say, we could actually manipulate our own microbiomes to better outcomes. One particularly icky example of this is the fecal transplant, which has actually shown some impressive results, even if the jury is still out on whether we should be eating probiotic yogurt.

Of course, bacteria aren’t the only tiny creatures in our environment: down the hall, in a talk on marine biodiversity, University of British Columbia researcher Curtis Suttle said that when you go swimming, you swallow as many viruses as there are people on Earth—and they’re generally perfectly safe. We’re only beginning to learn about these viruses, too, and the promise they hold for developing new drugs, to name just one application.

From the tiniest microbes to big ideas, the day ended with a talk from Mike Lazaridis on the power of basic research. Described as the “instigator of the smart phone revolution,” Lazaridis, who also founded the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics, spoke warmly of his love of physics. He urged the crowd to have faith in the sort of science that seems to have no practical application at all—he pointed out that quantum mechanics once would have qualified—because that’s where the next big ideas will come from. As for the smartphones that made him famous, “devices are just ideas,” he said, “made into a form we can hold in our hands.”