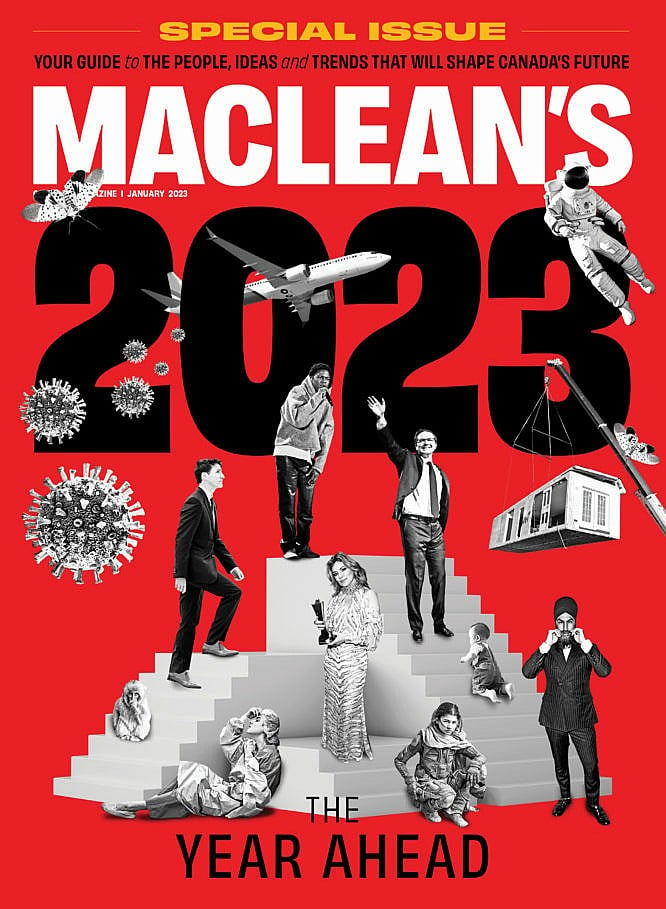

The Year Ahead: Food in 2023

“It seems patrons do not want a side of exhaust with their brunch”

Vertical farming is a solution to many problems we face in 2023: it helps fight food insecurity and farmland shortage, and it’s energy- and water-efficient. (Illustration by Selman Hosgör)

Share

This story is part of our annual “Year Ahead” collection. Read the rest of our predictions for 2023 here.

The lockdowns may be largely behind us, but our pandemic eating habits continue. In 2023, Canadians will keep dining al fresco and ordering on apps. We’ll look for healthier and more sustainable options—and pay a lot more for everything. Here’s a look at the year ahead in the world of food:

1. Street patios will spark a fight for public space

Curbside dining—one of the few things that made pandemic life tolerable—is here to stay. Toronto has made its popular CaféTO program permanent and, after Vancouver’s Temporary Expedited Patio Program ended and restaurant owners voiced their frustration with the clunky replacement process, the city relaxed requirements and cut red tape. And yet the future of extended patio season is about more than heaters and twinkly lights. With public space at a premium, it will require a balancing act between competing needs and user groups. More than 90 per cent of respondents to a City of Toronto survey endorsed the continuation of the CaféTO program, but there were also many complaints: about noise, lack of accessibility, and congestion on sidewalks and streets. Some Reddit threads were filled with gripes about too many cars crawling by on the adjacent street lanes. It seems patrons do not want a side of exhaust with their brunch.

2. Food prices will still be a conversation starter

Last year, grocery prices increased at the fastest rate in 40 years, and nearly a quarter of Canadians bought less food because they just couldn’t afford it. Something had to give, and in the end it was… Galen? Last October, the president of Loblaws announced a temporary price freeze on 1,500 private-label products, following in the footsteps of European grocers—a PR stunt, perhaps, but a welcome one for cash-strapped shoppers. Food prices will level out this year, but they’re not going down. The Daily Bread Food Bank anticipates 225,000 monthly clients by March, up nearly fourfold from pre-pandemic levels.

3. Vegan chips and Oreos will take over the junk food aisle

The global vegan snack market is set to reach US$80 billion by 2030, which means—noble goal alert—the search for better junk food is on. Vegans and flexitarians will find supermarket shelves stacked with purpose-made treats like PeaTos vegan cheese curls. (It also turns out some products were vegan all along, like some Ritz Crackers and most Oreo cookies.) There’s more vegan fast food on the menu too, with the popular Ontario plant-based burger chain Odd Burger trading on the TSX and ready to add another 40 locations to its roster of 92.

4. We’ll crave fake seafood

There’s rice flake shrimp, pea- and seaweed-extract shrimp, vegetable root starch shrimp, mushroom-extract shrimp… If Forrest Gump got a 2023 remake, Bubba’s pitch might sound something like that. Riding a wave of investment, food producers are creating more sustainable seafood alternatives that address both overfishing and climate concerns, appealing to consumers who love sushi and the ocean in equal measure. The Good Food Institute, a U.S. think tank, has tracked 120 new companies specializing in imitation or lab-cultivated products like caviar made from seaweed, 3D-printed plant-based seafood and shrimp created from algae. Part of Protein Industries Canada, Toronto’s New School Foods is making waves with its whole-cut salmon filet facsimile—coming soon to a seafood spread near you.

5. We’ll seek new solutions for vanishing farmland

In vertical farming setups, crops are stacked storeys high in indoor, climate-controlled environments. Each individual plant is monitored (giving a whole new meaning to data farming), and harvests are efficient and predictable. The whole enterprise could help fight food insecurity and climate change. Advocates for traditional farming are quick to point out just how energy intensive vertical agriculture can be: some of these plant factories use as much as 100 times more energy than a regular farm. The rebuttal: many use at least some renewable energy—not to mention a lot less water and a lot less land. Canada’s first net-zero vertical farm, meanwhile, is in the works in Toronto. According to the 2021 census, Ontario is losing 319 acres of land—the rough equivalent of an average-sized farm—per day to urban sprawl. Vertical farms like Toronto’s Elevate, Sky Greens in St. Albert, Alberta, and Ottawa’s Growcer could be part of the agritech solution, providing fresh, flavourful food and reducing our reliance on high-footprint imports.

6. Women hunters will put meat on the table

More women are taking up arms these days—a product of rising food costs and a collective desire to source food ethically. In 2021, British Columbia issued licences to 12,000 women hunters, twice as many as there were 20 years ago, and the number in Alberta rose by 20 per cent between 2016 and 2020. Organizations like the Alberta Hunter Education Instructors Association offer fully equipped mentored hunts that lower the sport’s barrier to entry, and women-only hunting groups and educational programs are popping up from Nova Scotia to British Columbia.

7. Restaurants will have a stake in food delivery

Despite a rebound of in-person dining, most Canadian consumers are still ordering as much takeout as they did during pandemic lockdowns. Third-party platforms like Uber Eats and DoorDash are swallowing larger slices of the food-delivery pie every year, and restaurants are looking for ways to protect themselves. British Columbia has introduced legislation aimed at capping fees charged by the apps. Megacorps like McDonald’s are bringing the competition inside the tent, partnering with Uber Eats and DoorDash for an improved delivery experience (and, presumably, a reduced commission rate). And smaller shops are keen to reduce their reliance on third parties through integrated ordering technology and in-house delivery.

8. We’ll harvest dinner in our own backyards

Thanks to rising interest in both locavorism and food sovereignty—that is, the right to access healthy, culturally appropriate, sustainably produced food—city-dwellers are growing their own crops. Across the country, urban agriculture is flourishing: Edmonton’s Urban Farm doubled in size in 2022. Toronto’s Fresh City Farms signed a new lease on a 4.5-hectare plot that it plans to share with other organizations, including a farming collective geared toward single, racialized mothers. And the city of Mississauga just launched its first urban agriculture strategy, with nine community gardens and one teaching garden designed to grow the urban agriculture scene and make it more inclusive.

9. More bottle shops will go booze-free

Last year, the authors of the cheerily named Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries and Risk Factors Study concluded that there is no safe amount of alcohol for adults under 40. That might work out just fine: Gen Zers drink 20 per cent less than millennials did at the same age, opting instead for reduced- or zero-alcohol alternatives. Driven by surging sober-curious demand, the market is exploding—global sales are expected to hit $90 billion by 2030. Canadian small-batch startups include Acid League, which makes wine-like blends of fruits, teas and spices designed to pair with foods, and Ritual, known for its smooth and smoky Tequila Alternative. Non-alcoholic spirits are available at supermarkets and liquor stores, while dedicated boozeless bottle shops are popping up in Ottawa, Montreal and Toronto.

10. Tipping will become a thing of the past

With food services continuing to bear the brunt of the labour shortage, restaurants are hoping to attract talent by doing away with tipping. Over the last year, a slew of spots, including Toronto’s Richmond Station and Marben, Ottawa’s Aiana, Montreal’s Larrys and Vancouver’s Folke, eliminated gratuities, and more restaurateurs are following their lead. Many places now offer staff higher starting wages, comprehensive health benefits and paid time off. That’s worth a lot to employees in an industry plagued by burnout, addiction and other mental health issues.

This story is part of our annual “Year Ahead” collection. Read the rest of our predictions for 2023 here.

This article appears in print in the January 2023 issue of Maclean’s magazine. Buy the issue for $9.99 or better yet, subscribe to the monthly print magazine for just $39.99.