The short, complex life of a writer of short, complex stories

The precursor to both Stephen King and mommy bloggers alike, the late Shirley Jackson—you may know her story ‘The Lottery’—haunts us still

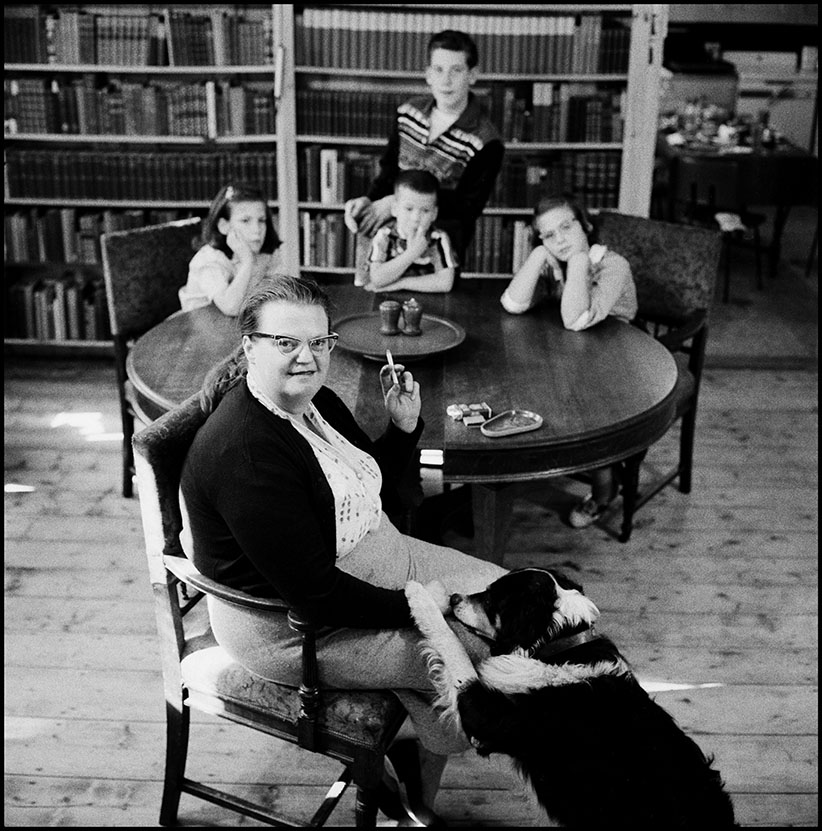

USA. 1956. American author Shirley JACKSON. (Erich Hartmann/Magnum)

Share

Fifty years after her death, Shirley Jackson’s reputation has cemented itself around her marvellous propensity for the macabre. It’s possible you studied “The Lottery,” her 1948 New Yorker short story about a most peculiar small-town rite, in high school—or know it by reputation; it sparked an outcry among the magazine’s readers. You may have been terrified by her novel The Haunting of Hill House (turned into a good movie in the 1960s and a terrible one in the 1990s) or disquieted by the one after that, We Have Always Lived in the Castle. Or you may have noticed that writers like Jonathan Lethem, Kelly Link, and Stephen King consistently champion Jackson’s work; their particular blends of realism and horror owe much to her unique distilling of genres.

As masterful as Jackson was with tales of everyday horror, there was a lot more to her work. A story such as “After You, My Dear Alphonse,” which expertly skewered suburban racism and class condescension through conversations between a mother and her child’s friend, may be even more relevant in today’s turbulent times as it was when it was first published seven decades ago. In the era of mommy bloggers, her memoirs of bringing up four children, Life Among the Savages and Raising Demons, re-released this year, are no less so.

As a new collection, Let Me Tell You, demonstrates, while Jackson published a lot during her lifetime (cut short by illness at 48 in 1965), she left an equal amount, if not more, unpublished—as her children discovered while sorting through her archives at the Library of Congress in Washington. “Hundreds and hundreds of short stories,” says Laurence Hyman, the eldest of Jackson’s children, who, with his younger sister Sarah Hyman DeWitt, put together the 1977 collection Just an Ordinary Day, but realized “there were many others that were worthy of publication.”

“Growing up in that household, we didn’t recognize, but certainly [do] now, how unusual and creative and very textured a domestic life we had,” says Hyman. Jackson’s children nearly named the collection “Garlic in Fiction” after a fascinating essay by Jackson on how her stories relied on a telling detail. It’s a favourite piece of Ruth Franklin’s, who wrote the introduction to Let Me Tell You and is finishing a biography on Jackson. “It’s the perfect housewife-writer image,” says Franklin. “It pinpoints one of the things Jackson does so well: the absolutely perfectly uncanny, telling detail. It’s that disconcerting jolt to the story, even if you’re not fully aware of it.”

The strength of the collection is the breadth of Jackson’s talent, which moves from literary criticism—she was “mortally afraid of offending Dr. Seuss” and praised the “unfashionable novelist” Samuel Richardson—to fiction and a wealth of humorous stories of domestic life. Jackson, in an early diary entry unearthed by Franklin, referred to “this compound of creatures I call Me,” which seems an apt description.

Interestingly, the title story of Let Me Tell You is unfinished. Hyman explained there were “lots of stories that we loved, but because they weren’t finished, sadly, we decided weren’t ready or publishable. We certainly didn’t want to try to finish them ourselves.” But he and DeWitt include the opening of an unfinished story on witch-burning as the frontispiece. “She wrote a page of that, always intending to finish. We felt the first paragraph says worlds—all you need to know about the story.”

Let Me Tell You includes a cross-section of Jackson’s line drawings, 800 of which were discovered in her archives. “We had no idea they had been kept,” Hyman says. “I remember many from my childhood. My mother would hang them up on the fridge and the study door. They are wonderful, a full range, from artistic sketches to Thurber-esque cartoons,” referring to the New Yorker humorist, a friend of Jackson’s.

“I loathe autobiographical material, because if it’s dull, no one should have to read it anyway, and if it’s interesting, I should be using it for a story,” Jackson wrote. She stuck to this credo with spellbinding ease. Franklin hopes the new collection will bring more readers to Jackson. The greater hope is that readers see why Jackson is more important than ever before.