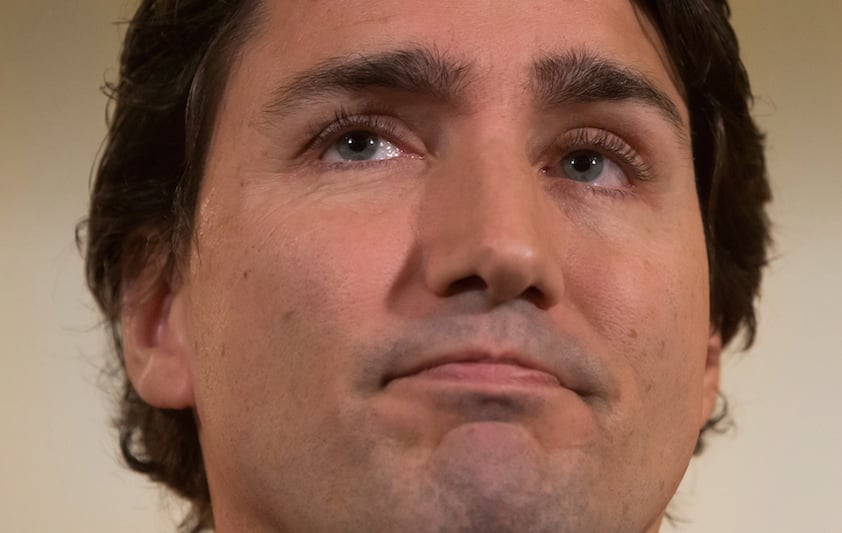

Does Justin Trudeau want to be the Data Prime Minister?

The Liberal leader quizzes the Governor of Maryland

Share

Maryland Gov. Martin O’Malley, the former mayor of Baltimore and a man who might be the next president of the United States, was in Ottawa yesterday to address an audience at the Chateau Laurier. After his prepared remarks, the governor was joined on stage by Liberal Leader Justin Trudeau for one of those friendly chats that are de rigueur at these sorts of things.

O’Malley had twice used the phrase “data-driven” during his short speech, and the use of data to drive and direct government policy is a trademark of his time as governor and mayor. Trudeau’s first question for O’Malley was about that.

Here’s the full exchange that ensued. (At a couple small points, my recorder failed to pick up the sound well enough to transcribe.)

Trudeau: When we first met, a year ago, at the Center for American Progress conference in Washington, D.C., we both geeked out a little bit on data. And I’d love to hear a little bit more about CitiStat and StateStat. We have a real need, and one of the centres of the platform that I’ve been pulling together to govern this country better, possibly, in the future, is very much on evidence-based policy, on science, on data. We have a government that, unfortunately, has cut the long-form census, which gives us information about how government services are . . . communities, has gone after scientists and evidence-based policy in general. How important is data and what are the tools that you developed and can they be scaled up to a nationwide vision, not just city or state?

O’Malley: Great question. I was very fortunate when I was elected mayor of Baltimore, and that I had been watching our city struggle with what had become the biggest violent-crime problem of any city in America, and that I saw in New York City what they were doing with performance-measured policing and this new way of leadership called CompStat: timely, accurate information shared by all . . . affecting tactics and strategies and the relentless follow-up that allows you to determine whether what you’re doing is working or not working—in this case, to reduce violent crime.

And so we took that approach and we made that our enterprise-wide approach to all of city government. And we weren’t doing it to be clever or to win awards, though we did win the innovations in government award from the Kennedy School at Harvard. And let me tell you what the crux of the innovation was. Usually, governments, until that time, even municipal governments, to the extent they measured anything, they measured only inputs. And they measured them annually, in something called a budget. And Mark Morial, the former mayor of New Orleans, once said to me, “Kid, if you ever want to hide something, make sure you put it in the city charter or the city budget, because nobody ever reads either one.”

So our big innovation was that we started measuring outputs and we started measuring those outputs, not once a year, but every day. And then, every two weeks, we would gather around . . . the common platform that is GIS technology that allows all those formerly separate silos of endeavour to land on the same map. And, instead of playing scramble, we started running plays.

And, man, it’s amazing, when you create a compelling scoreboard that everyone in your organization can see, when you itemize the leading actions that we’re pursuing together to move to the big goal—in this case, violent crime reduction—and the leader, the modern leader, insists upon a cadence of accountability, where people get together regularly, it’s amazing how much progress smart people can figure out, not in a prescriptive way, not in an orders-from-on-high way, but in a collaborative, questioning way.

And so that’s what we did across all city government. It wasn’t an accident, in the United States, that the top three cities with the biggest reductions in violent crime over the last 15 years have been Los Angeles, New York and Baltimore, because all three cities embrace this. And, as I’ve travelled around the country over this last year, I’ve found that, in stark contrast to people’s opinions about our Congress and how it functions, or does not, people are feeling a lot better about how their cities are run.

O’Malley had brought some slides with him and proceeded here to go over a series of charts, graphs and maps. “An essential part of this is also setting strategic goals: the modern leader being willing to make him or herself vulnerable for achieving those goals by telling the public: This is what we want to achieve, by a date,” he said. “The difference between a dream and a goal is a deadline. We’ve set up a number of dashboards so citizens can see whether we’re on track or not.”

So is Trudeau interested in following O’Malley’s lead? Here is the official word to me from Trudeau’s office:

Governor O’Malley’s insights into the importance of data-driven and evidence-based policy in governance have huge implications here in Canada. Mr. Trudeau believes in many of the same principles of setting targets and measuring progress in order to get the best public policy results.

There’s something here, I think, in the current challenge for progressives who want to win the public’s support for a more activist government, but, more generally, this speaks to the principles of open data and the burgeoning desire to see the work of government better analyzed (including the Moneyball for Government initiative).

“Evidence-based policy” seems both an obvious idea and an easy talking point for the Harper government’s critics and rivals, but the execution of such an agenda is complicated by several factors. There is the matter of adapting an approach that has been used at the city and state level to the federal level, the federal government being less responsible for direct service delivery. There is the question of political will: a prime minister and government having to be willing to deal with what the data show. There is, as David Eaves has written, the potential for the politicization of data.

And it’s not so easy as imagining that data will provide definitive answers that bring policy debates to tidy conclusions. There will be debates over different measures and data that are dismissed. But we might at least hope that there is some basis for the debates that are had. We could, at the very least, imagine that the government would estimate how jobs might be created by a $550-million job-creation initiative.

All of this would probably start with restoring some kind of long-form census.

The degree to which Trudeau is tipping his hand, or what this will amount to in a Liberal platform, remains to be seen. But, as politics and policy, this is potentially intriguing stuff.