Let’s watch Stephen Harper dance around the Nadon controversy

And Thomas Mulcair pulls at loose threads

Share

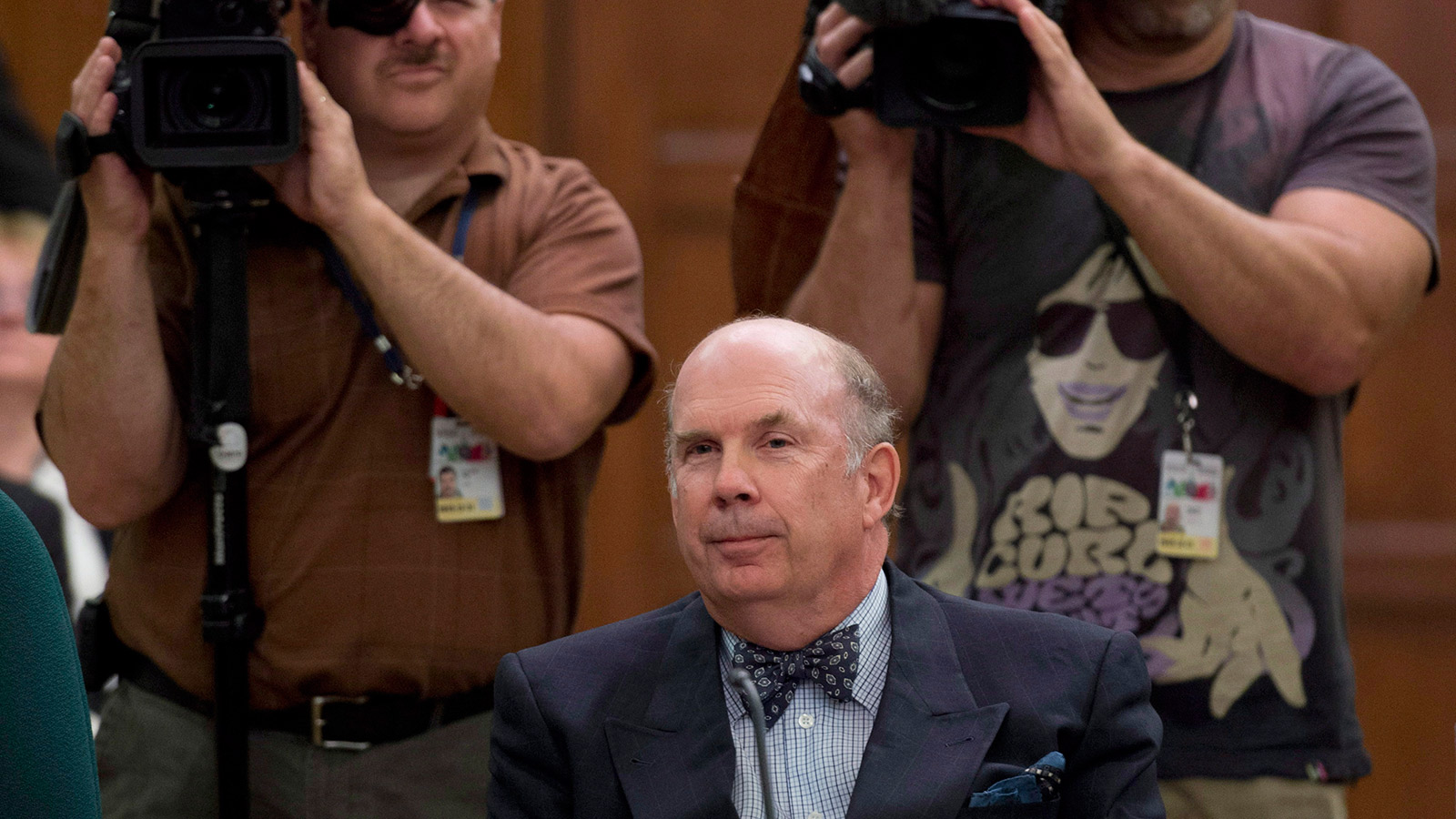

Let us mix our metaphors and say that while Thomas Mulcair pulled at the loose threads of the Marc Nadon appointment yesterday, Stephen Harper danced around the mess.

The NDP leader returned on Tuesday to his thesis of the day before—that somehow the government’s line has changed here—and to this the Prime Minister posited that the NDP’s line on Mr. Nadon had changed.

Mr. Speaker, the only changed story is from the NDP and the opposition, which had no objection to the appointment of Federal Court justices, and in fact no objection to Justice Nadon.

The trouble with this statement is that we don’t—can’t?—know whether the NDP raised any objection to Mr. Nadon or the idea of a Federal Court judge being appointed to fill of Quebec’s seats on the Supreme Court. All proceedings of the MP selection panel were confidential. We don’t even know how the members of the panel voted in determining the short list that was put forward to the government.

On that note, Mr. Mulcair quibbled.

Mr. Speaker, as my colleague has already had occasion to say, no one will ever be able to claim that she agreed with the appointment of Justice Nadon.

In subsequent answers, Mr. Harper would qualify his first statement with reference to NDP critic Francoise Boivin’s public comments on Mr. Nadon.

Mr. Speaker, once again, to correct the record, what the critic of the NDP said on Justice Nadon is that he was a great judge and a brilliant legal mind…

Mr. Speaker, I have to repeat again what the NDP actually said about Justice Nadon: a great judge and a brilliant legal mind. I guess one could interpret that as opposition but I tend to interpret that as support.

That’s fair. As I wrote on Monday, if the NDP had any objection here, it might’ve been better off expressing that objection as soon as Mr. Nadon’s nomination was announced.

But Mr. Mulcair had other questions.

“Why did the Prime Minister not simply seek the opinion of the Supreme Court before appointing Justice Nadon?” the NDP leader asked. The Prime Minister deferred to the wisdom of the experts he consulted who believed that Mr. Nadon was eligible.

“If the Prime Minister knew that this appointment would be challenged,” Mr. Mulcair wondered, “why did he not try to change the appointment rules before appointing Judge Nadon?” The Prime Minister deferred to his experts.

Since Beverly McLachlin’s flagging of the issue became known, it has variously been the government’s position that it believed the issue of Mr. Nadon’s eligibility “might” or “could” or “may” have or was even “likely” to come before the Supreme Court. The Justice Minister had publicly flagged a potential issue with the Supreme Court Act last August. And yet, the government went ahead and nominated Mr. Nadon in September anyway. And it was then not until two weeks after the appointment was challenged by a Toronto lawyer in October—that after Mr. Nadon was sworn in as a Supreme Court justice—did the government act to refer the matter to the Supreme Court and attempt to amend the Supreme Court Act: simultaneously asking the Court whether its amendment was constitutional and telling Parliament that the amendment was constitutional.

If the Prime Minister wanted to appoint Marc Nadon, the government might’ve sought to gauge the possibility of a constitutional amendment to ensure Mr. Nadon was eligible (after releasing a response to an order paper question on Monday that suggested this was still a possibility now, the government seems to have decided it’s not a possibility). Or it might’ve sought out the Supreme Court’s guidance before putting forward a nominee.

Instead, the Prime Minister apparently decided to take his chances.

So how educated a guess was that?

So far as we know, the government had one legal opinion (from former Supreme Court justice Ian Binnie) and two individuals (former Supreme Court justice Louise Charron and constitutional scholar Peter Hogg) who concurred with that opinion. Other than that, the government won’t say. Liberal MP Irwin Cotler has asked specifically whether a Quebec jurist was consulted or whether the Justice Department offered an opinion, but on both counts, the government is claiming solicitor-client privilege.

Mr. Harper went so far yesterday as to claim that “all legal experts had long understood … that Federal Court judges were eligible.” And the Prime Minister used the phrase “long-standing” five times yesterday in defending the government’s nomination of Mr. Nadon.

I referred it to a range of legal experts, all of whom agreed that as had been long-standing practice, Federal Court judges were eligible for appointment to the Supreme Court…

We decided to proceed with an appointment to the Supreme Court according to long-standing criteria…

They all agreed that the long-standing view that Federal Court judges were eligible should not be challenged…

That is why we proceeded according to long-standing practice, and that was the appropriate course of action…

The Liberal Party, according to a long-standing practice, did not object to the naming of Federal Court judges to the Supreme Court and certainly did not object specifically to the naming of Judge Nadon.

What precisely is the “long-standing” aspect of this?

Previously, the Prime Minister has said it was long-standing practice that Federal Court judges were appointed to the Supreme Court. (I’ve asked the PMO if they’d like to further clarify the Prime Minister’s adjective and will post a response if one is offered.)

In a paper prepared after Mr. Nadon’s nomination, Carissima Mathen and Michael Plaxton explored the relevant history here. The two academics note no objection to the appointment of Federal Court judges in general, but specify a distinction between the appointment of a Federal Court judge and the appointment of a Federal Court judge to fill one of Quebec’s three seats on the Court: seemingly the crux of Mr. Nadon’s situation.

It is worth taking a moment to consider what we have not argued. First, we have not claimed that judges from the Federal Court or Federal Court of Appeal can never be appointed to the Supreme Court of Canada. As we noted above, Binnie’s reading of section 5 of the Supreme Court Act is entirely reasonable. Indeed, when we read that provision in light of section 30(1) of the Act, his argument appears even stronger. This means that there is no question of the legality of the appointments of, for example, Mr. Justice Iacobucci, Mr. Justice Rothstein, or Madam Justice Arbour. The difficulty with appointing judges directly from the Federal Court or Federal Court of Appeal arises only when they are being appointed to fulfill the requirements of section 6.

Mr. Nadon would seem to be the first attempt to appoint a Federal Court judge to one of Quebec’s seats on the Supreme Court.

I traded emails with Mathen last night—note: I did not specifically put this “long-standing” notion to her—and she argued further as follows.

If you just look at past practice, you will come to the inevitable conclusion that every Prime Minister until this one was operating on the understanding that any persons appointed under s.6 from prior judicial positions, had to be sitting on Quebec courts. This was the practice since the enactment of the Federal Courts in the 1970s. The conclusion is especially powerful when you consider that Fed Ct judges were being appointed under s.5 (the general appointment formula for the other 6 seats). Gerald LeDain is the best example: a Quebec trained civilist who was nonetheless appointed under an Ontario seat. I would point out, as well, that amendments to the Supreme Court Act as late as 2002 confirmed different treatment for Federal Court judges who may be appointed on an “ad hoc basis” to fill temporary vacancies. They are expressly mentioned as eligible for such appointments, EXCEPT in relation to section 6.

In his own paper, University of Montreal professor Paul Daly has pointed to a precedent from 1918.

On the other hand, Peter MacKay has asserted that other Federal Court judges from Quebec applied to fill the most recent vacancy.

However understood, it is the section 6 distinction—relating to the requirements of Supreme Court justices representing Quebec—that ultimately scuttled Mr. Nadon’s appointment.

Perhaps someday we’ll get a full airing of why the government proceeded as it did here and what all occurred behind closed doors—from the appointment of Mr. Nadon, to the selection panel’s work, to the government’s challenge of the Chief Justice and subsequent retreat from that challenge—but for now you can merely pile up questions. (For those scoring at home, that’s Mr. Mulcair pulling at loose threads, as Mr. Harper dances around a mess, and questions pile up.)

Meanwhile, of course, the Court is still short a judge. Though the Globe reports this morning that the government at least has something of a plan for filling that spot.