What is John A. Macdonald’s legacy, 200 years after his birth?

A panel of experts toasts the complicated, visionary Sir John A. Macdonald on the occasion of his 200th birthday

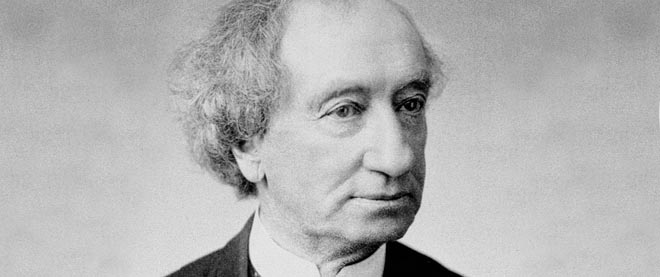

People – Sir John A. Macdonald. (1815-1891) National Archives of Canada/CP

Share

Jan. 11, 2015 will mark the 200th anniversary of the birth of John A. Macdonald, our first and perhaps greatest prime minister.

To mark the occasion and consider Macdonald’s significance, Maclean’s convened a gathering of three John A. aficionados: Richard Gwyn, the journalist and author who wrote The Man Who Made Us and Nation Maker, a two-volume biography of Macdonald; Patrice Dutil, a professor at Ryerson University and co-editor of Macdonald at 200: New Reflections and Legacies, a collection of essays on Macdonald’s influence; and Jane Hilderman, research manager and acting director at Samara, an advocacy group dedicated to improving citizen engagement and public life, and a member of Toronto’s Friends of Sir John A. Macdonald organization.

Reporter Aaron Wherry gathered the group at Sir John’s Public House, the building in Kingston, Ont., that housed Macdonald’s law office from 1849 to 1860 and is now a pub dedicated to his memory. This is an edited transcript of their lively conversation.

Q: So we’re here in Sir John’s Public House, in Kingston, a little bit ahead of Sir John’s 200th birthday. What should we be celebrating?

Gwyn: I think you could compress it into a sentence: No Macdonald, and none of us would be Canadians. There would be no Canada. Everyone took it for granted that Canada wouldn’t last. It made no sense as a nation. We were divided between the French and English, between Catholic and Protestant, between Aboriginal and European, etc. Macdonald got us through that period, when we were very very vulnerable and could have just been lost like that. And that’s a big deal.

Dutil: The thing that strikes me most about Macdonald is his optimism. He had a sense of Canada, he had a sense that something could take shape north of the United States in this behemoth that was being created in the mid-19th century, and he had this idea that something good, something different, could happen here. He’s the guy who’s always asking “Why not?” I think that, on his 200th birthday, that spirit needs to be celebrated.

Hilderman: As a young person in Canada, looking at our nation where we are now, it feels like we have a lot of big challenges ahead of us in terms of managing an aging population, having a generation like mine that feels very squeezed in terms of student debt and housing, and also thinking about future generations, the environment. Macdonald approached those problems without intimidation and asked for a big vision for Canada. Sometimes you can bring a big idea, and with a lot of great hard work, you can build something and overcome seemingly insurmountable odds.

Q: How much of the country we are now is reflected in what Macdonald was aiming for?

Gwyn: I think quite a lot of it is here still. He created the first distinctive Canadian thing. Before that, basically we were guys who lived in North America and didn’t want to be American. That’s pretty weak grain to build anything on. In the west, Macdonald sent out a force that he created out of nothing called the North-West Mounted Police. He gave them two instructions: one was that no liquor is to come from America up to Canada. The second was the rule of law. And because of him, the west in Canada was distinctive from the west in the United States, although topographically of course they were absolutely identical. And the same kind of people—settlers and all that. He created the start of a distinctive way of being North American, and that’s a huge contribution, and we’ve been building on that in different ways ever since.

Dutil: John A. Macdonald turned the prime ministership in this country into a very strong centralizing force. Something else that Macdonald gave us was a national park: Banff, 1886-87, 30 years before the Americans [started their National Park Service]. John A. says: “There’s a place there, it’s not perfect, we can make it better, but there’s a place there that needs to be preserved.” Again, he’s thinking ahead, he’s thinking generations ahead, and he says that using the rule of law, we’re going to set markers and we’re going to place this piece of God’s land away from anything that man can do or waste.

Q: What’s his legacy? Is there something there for people to say, “Well that’s because of John A.”?

Hilderman: The railway immediately comes to mind, whether it’s to move horses from one end of the country to the other or when I took the train here today. There’s a symbol in how we bridge this huge, vast geography and we still echo back to that as a symbol of the railway of the future. Maybe it’s broadband Internet or whatever, but how do we connect our country? John A. was thinking about that 200 years ago.

Q: Concerns get raised about Sir John A., particularly his attitude toward certain races, his drinking. How should we deal with those things? Should we understand them in the context of the time? Should they be a major part of the discussion about who he was?

Gwyn: Well it’s part of him that he did drink more than he should have and that’s a fact of life. By the way, Ulysses S. Grant was a complete drunk but it’s not something that the Americans go on and on about. We do about Macdonald. I will say a couple of things about his drinking: One, he quit, which is damn hard for anybody to do. Today you’ve got all kinds of expertise, and it’s still very hard to quit. The other thing is there was a very good reason for drinking liquor in 19th-century Canada, and that was that ordinary water was so appalling that if it merely gave you diarrhea, you’ve done very well. That was a practical thing and a lot of Canadians got drunk out of their minds so they wouldn’t get a whole lot of diseases. I won’t go into detail, because it’ll shock your readers, but it was awful.

Dutil: But Richard, it’s important to remember that the drinking was so bad in John A.’s society that a whole temperance movement rose out of it. I mean, a social revolt against men drinking beyond what was reasonable. He’s very much a man of his time. I think it’s very important that he overcame that vice; for me that’s one of the themes of John A. that I think is so attractive. Here’s this guy who’s born with a certain mindset in a privileged class, but what’s interesting about him is that his ideas evolve in his life. His ideas toward women evolve, his ideas towards Catholics evolve, his ideas toward Aboriginal Canadians evolve. There’s an evolution to this man, a march toward rethinking his own prejudice, that I think makes him a modern man and a man worth emulating. He was not without fault, we’re all agreed on that. He’s a human being but he made the effort to sit back and say, “Am I really thinking the right thing here? Should we be thinking something different?” For me, I think he’s an exemplar of that.

Q: So if you talk about John A., the first that most people understand about him is that he liked drinking.

Dutil: It’s a terrible thing, a terrible cartoon of the man.

Gwyn: Why do we do that?

Hilderman: I think because you keep telling stories.

Gwyn: I must tell you this anecdote. He could rise above anything. There was a rally in southern Ontario in the open air. His opponent is speaking, Macdonald is seated at the back of the stage and he’s been drinking. He gets to his feet, and I hate to say this, but he vomits. That’s the worst thing a politician can do, that’s the end of his career. You have insulted your audience unspeakably. Macdonald is now dead, politically. What does he do? He says to the audience, “I’m terribly sorry, I don’t know why it is, but whenever my opponent speaks, I lose my stomach.” He had the whole audience [eating] out of his hand. I’m not sure what that proves, but it’s a good story.

Hilderman: I think Sir John A. has other warts that are worth more consideration than his drinking. But history is complicated and it’s good not to brush over those facts. Framing what was a personal struggle for him, what we would call an addiction now, is a reminder of what a challenging role he had and the odds he overcame to be as productive as he was.

Q: Do we need Sir John A.’s vision today?

Dutil: We are in a historic moment where a lot of institutions are being torn down. Where the value of institutions has been diminished because they’re not seen as responsive to these wicked problems of modern-day Western society. Because we are all individually much more informed, we have a much greater sense of power individually and we’re all better connected, there is an onus on the government, on the state, to collaborate and find ways of communicating. So the spirit of John A. can still inspire in the sense that we want to build for the future, we want to build flexibility, we want to be responsive.

Gwyn: In one way Macdonald was lucky: he was treated with a certain deference—prime minsters were, cabinet ministers were. There was a willingness to believe they were doing their best, a willingness to give them space. Today there’s a tendency to say you screwed up and that’s the end of the discussion. The second point is that if you’re trying to build a nation out of a country that wasn’t really a country, which is what the challenge was, the public knows what you’re trying to do instinctively. Today it is much harder to get that sense of vision, or direction. We should recognize that Macdonald was a bit lucky. So was Laurier, in the same way. Nation builders are always given the benefit of the doubt.

Q: If we stuck Sir John A. in a time travel machine, we’d have to explain Twitter.

Dutil: He would get it! I mean, this guy was the master of the quip. With that tool in his hands, he would devastate the rest of the Twitter feed. He’d be fantastic, I have no doubt about that. Plus he had this charm, everybody recognizes that’s an important thing. Especially today, when a lot of politicians feel they must repress their personality for fear that some aspect will be magnified and distorted and misunderstood. John A. had this fantastic personality. He was a friendly man and a humorous man. He made people at ease and I think that was part of his magic.

Q: What would you say is the most under-appreciated fact about John A.? What stands out as the one thing we don’t talk about enough?

Dutil: What impresses me most about him is his dogged work ethic. He worked night and day—at the desk, but also communicating, talking to people. That’s part of the story that’s been completely forgotten or been underemphasized. This guy worked everybody under the table. Never mind drinking them under the table, he worked them under the table.

Hilderman: People are often surprised that he was an advocate for women’s right to vote. If he had his way—Parliament ultimately defeated his proposal to give women the vote—but had that succeeded, we’d have been the first country in the world to do that.

Gwyn: He was highly intelligent. We all think of Pierre Trudeau as the most intelligent prime minister. An expert would say Trudeau kept on making sure that everyone knew he was the smartest man in the room. Macdonald never did that. And what Jane just said about him trying to get the vote for women, that was staggering. There was no suffragette movement in Canada. There was none in Britain until 1885. The only place there was one was in the United States, with a very charismatic woman, Susan B. Anthony, but it was right on the margins of politics then. He not only said women should have the vote, but he said it was inevitable. The MPs must have been shocked out of their minds. He said it was inevitable that sooner or later women will take their positions as equals in society. The only person I know of in the world who thought that way at that time was John Stuart Mill, one of the finest minds in the world of the 19th century.

Q: The idea of John A. and greatness. Is he great to you?

Hilderman: If you’re not uncomfortable with something about your hero, then you probably don’t know them well enough. I think about the Famous Five, who I also hold in great esteem, and Emily Murphy was one of the leading advocates of eugenics in Canada in addition to advancing women’s rights. It’s complicated. This goes to recognizing the whole person and to hold up some vision of perfection for leadership is probably misplaced. I look to Sir John A. as a Canadian worth celebrating.

Q: Sir John A. versus Abraham Lincoln. Should Canadians look to him as Americans look at Lincoln?

Dutil: I think so. Unquestionably, for Canada he is more than Lincoln. He is Washington. His thinking, his vision, his restraint, his force, his bridge-building abilities, all those things we recognize in Washington we should recognize in Macdonald. Not innocently in the respect of accepting this, but as a starting point in terms of a dialogue. We need to talk history. History is a dialogue: you tell me a story, I tell you a story and somewhere along the line we will develop a line of inquiry, a line of debate, and we will think about the past. How does the past shape what we are today? Because it does, it does. Count the number of Washington streets and Lincoln streets and Jefferson streets in Canada, put them against Macdonald, and you’re gonna see a lot more of those streets than Macdonald. Spelled properly, small D not a capital D. It says a lot about how we wilfully forget who we are and the people who shaped our society, for good or bad.

Gwyn: I would regretfully disagree with you. Macdonald was not great in the meaning of the word great. You need circumstances to be great. The best example of this is Winston Churchill. Had there been no Second World War, he would have been a loser of a politician. He is, instead, the single most important person of the 20th century. Macdonald was really running a backward, poor, runty little hole: that’s all we were in 1867. What you are telling the story of, with Macdonald, is the Canadian version. We are not dramatic, we did not kill people. You need blood for it to be dramatic, but the history is ours and it’s very interesting and, lastly, it has succeeded. At the moment, our immigration program is easily the best in the world. When have we done anything that the world would have to recognize as the best?

Dutil: You mentioned immigration, but in fairness, it started badly. Macdonald imposed a head tax on Chinese. He had reasons to do it, but today he is vilified for his gesture and we have to recognize that. We think of ourselves today as progressive, and we can mock and be condescending to Macdonald, but are we really any better? In many ways, we have followed that path and are still establishing limits on how many people come to the country. They have to go through various hoops, there’s a point system, there’s all sorts of quota systems, we still choose the immigrants we want. It is a success, as Richard says; it’s also a legacy of the Macdonald era and an unsavoury one.

Q: While we’re on difficult topics: the English-French divide. How does John A. fit into that story of Canada?

Gwyn: Obviously Macdonald had a certain view on French Canadians—that they were a pain in the ass but they were our ass. You had to come to terms with them, you had to treat them with respect, even if you wish they would all speak English and that would solve the problem. But it wasn’t going to happen, and that’s when he made the beautiful phrase “treat them as a nation and they’ll respond as a free people and usually do generously. Treat them as a faction and they will become factious.” Nothing better has been said in terms of dealing with the fact that we were this curious country where there were two countries. But we have made it work.

Dutil: The reality is Macdonald is completely forgotten in Quebec.

Gwyn: So was George-Etienne Cartier, by the way.

Dutil: Absolutely. Cartier’s bicentennial was in September, and it was completely bypassed. For me, the best most eloquent [evidence] of Macdonald’s success on English-French relations is that Wilfrid Laurier, a francophone and Catholic, would be elected in 1896. The country was so solid after 30 years that people in Ontario will say, yeah, that French-Catholic might be worth a chance because we’re solid enough as a country to take it on. There’s a spirit of generosity, an optimism, that if we set the structures right, men and women will make it work.

Hilderman: The eulogy that Laurier gave after Macdonald’s passing included some of the most revealing words spoken in terms of how much Macdonald had influenced what leadership would mean in this country. It would mean French and English. Macdonald knew instinctively that you would have to build caucuses. He set that model and we’ve lived with it since.

Q: When we celebrate his 200th birthday, is there a lesson that Sir John A. teaches us or an ideal that we should have in mind?

Dutil: Think boldly. Take it on, take a big bite. Move forward. For me, it’s that optimism and the spirit of going further asking, why not? Why not do this or that? Why not try?

Hilderman: I do think the spirit was there to invite people from all over to come to our shores. You talk about him being very happy about the first Jewish immigrants arriving to Canada; that was unique in his period. He recognized that if you came to these shores and were going to be hardworking he’d have tremendous respect for you. He wanted to build a nation that included people like that.

Gwyn: He did. Of course, America set the pattern of vast immigration and we should always accept that as a great achievement. But we have come to match that and our diversity is incredible. In a way, that immigration and multiculturism is Canada’s tribute to Macdonald. He was a man of real ambition, he had a feeling that there was a validity to Canada when legitimately someone could say there’s no validity in this country. He understood that there was something distinctive about Canada.