How Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale became a vivid graphic novel

While creating her version of the story, Vancouver artist Renee Nault had a series of conversations with the renowned author

The Handmaid’s Tale (Graphic Novel) Illustrated by Renee Nault

Share

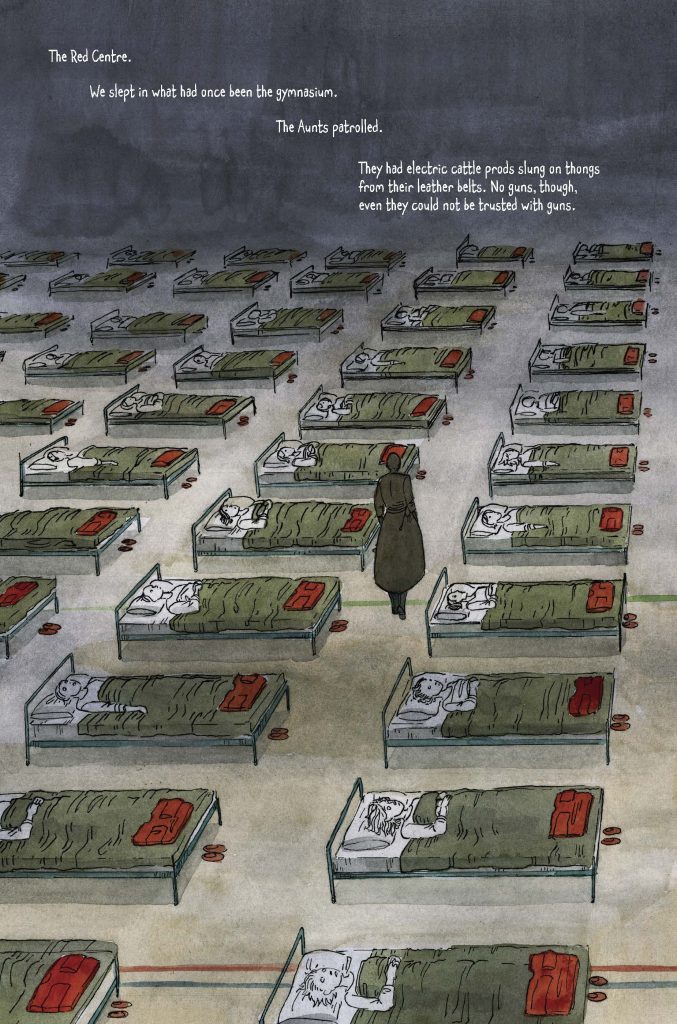

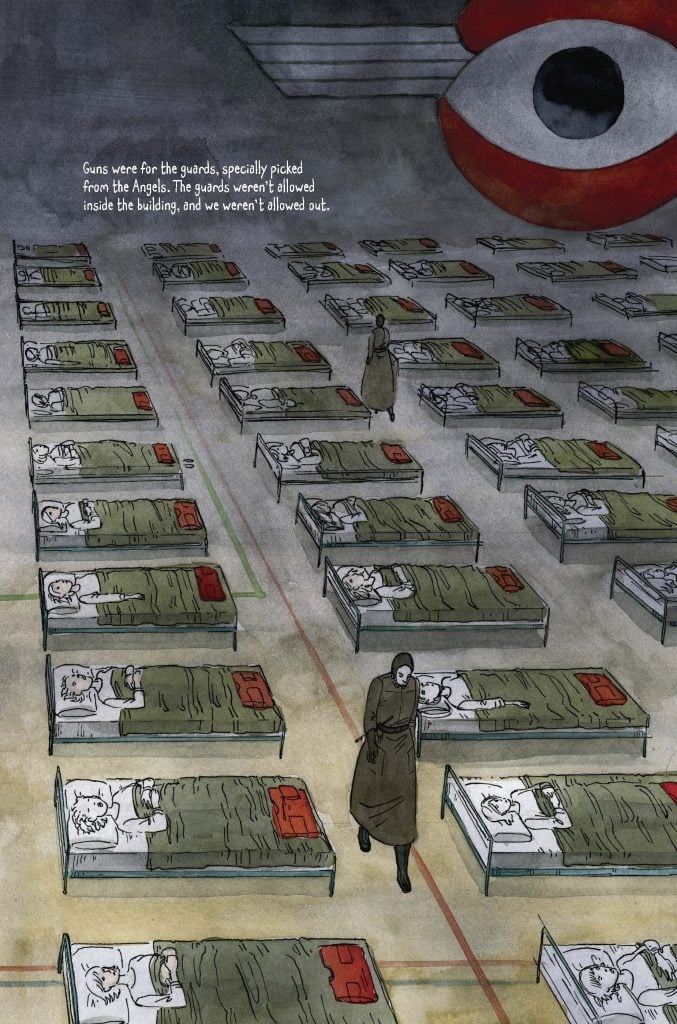

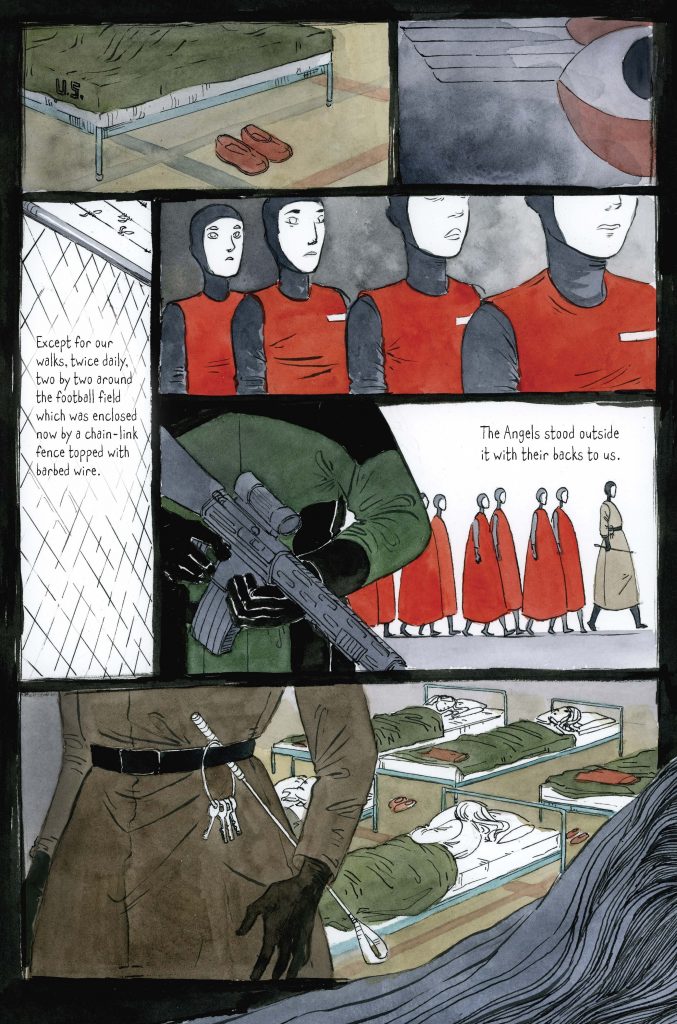

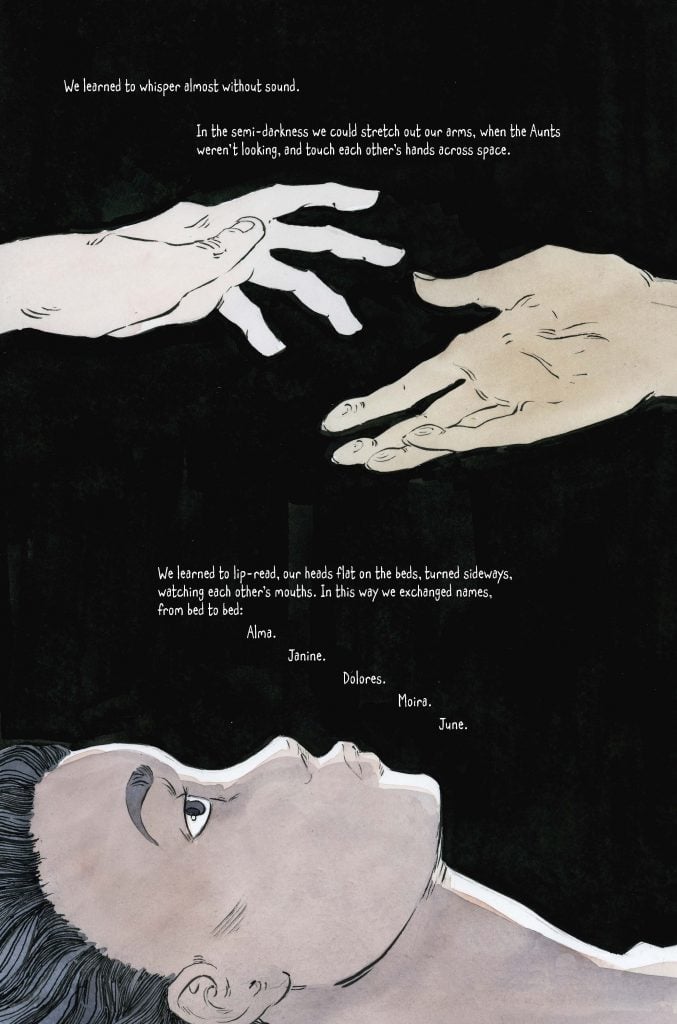

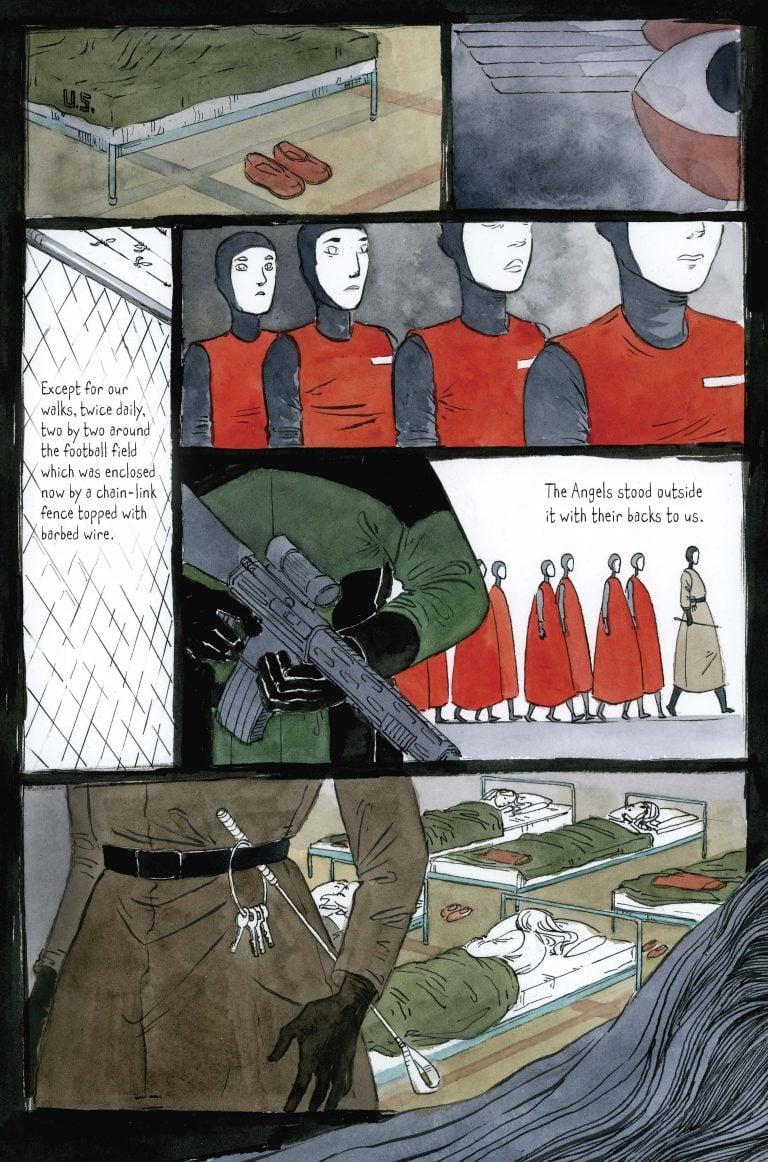

It’s hard to imagine a more colourful, more ironically vivid, dystopia than the Republic of Gilead in the hands of Renee Nault. The 38-year-old Vancouver artist has turned The Handmaid’s Tale, the most protean of Margaret Atwood’s novels—already refashioned as a feature film, opera, radio drama, stage play and ongoing TV series—into a strikingly beautiful graphic novel. Dystopias, places of ash and toxicity both physically and mentally, tend to be illustrated in shades of grey, Nault allows in an interview, “and that works, obviously—I used those tones a lot for the background. But I really wanted to pare down to the colours assigned to people’s social positions. Gilead is such a rigid, role-based society, and the novel has so much to say about gender roles as seen through women’s perspectives, that the first thing anyone notices about anyone else is what colour they’re wearing. Often, it’s the only thing, because those limited roles are all that matters in that society.”

The Handmaid’s Tale, the first of Atwood’s numerous near-future dystopias, was published in 1985, as conservative Christianity surged in political influence in the U.S. In the novel, a fundamentalist organization known as the Sons of Jacob launches a coup, killing the president and overthrowing the American constitution. In the new Republic of Gilead, organized as a militarized Old Testament society, the regime oppresses everyone who is not a white male believer. People of colour are ejected from society—and hence from The Handmaid’s Tale, set in a lily-white New England (outside its brothels, that is)—while women, valued only as breeders in a world where radioactive war debris and environmental pollution are wreaking havoc on human fertility, are virtual slaves, forbidden to own property or even to read or write.

READ MORE: For black women, The Handmaid’s Tale’s dystopia is real—and telling

The title character and narrator is so completely the possession of Fred, the local Commander who needs her womb to acquire an heir for his childless marriage, that her own name is erased. She is known as Offred, after her owner (“of Fred”), a very Atwoodian pun on both “offered,” in the sense of a sacrifice, and “off-red,” as Nault’s eye-popping palette makes clear. Like the other handmaids, Offred is dressed head-to-toe in sumptuous red; “wives,” the married women of the ruling class, are in blue and their unmarried daughters in white; the “aunts,” the disciplinarians who keep the handmaids in line and true believers in their own repression, wear brown; the “Marthas,” infertile women who cook and clean, are clad in green; “econowives,” poor women who perform all the respectable female tasks for their families, from child-bearing to housekeeping, have uniforms striped with the other caste’s colours. And then there are the Jezebels, who were a relief to draw for Nault.

The artist “really liked” doing the wild scenes at the ruling elite’s private bordello, “because I got to draw these crazy costumes and colours,” including old cheerleader uniforms, ragged underwear and swimsuits, and an on-its-last-legs Playboy Bunny outfit, complete with busted right ear. “They weren’t set out in the novel,” laughs Nault. “All it says is that the costumes were old or scavenged from other things.” Those scenes were a closer fit with Nault’s natural style, as displayed in her ongoing webcomic, Witchling. “My temptation is always to make everything really lush and beautiful because that’s what I like to draw. But Handmaid’s Tale is definitely a lot more minimalist. It just isn’t a happy book so it wouldn’t make sense for everything to have that really lovely look all the time. I had to use lushness and detail really sparingly, as when I wanted to imply wealth or power, like in the living room of [Fred’s bitter wife] Serena Joy.”

RELATED: Margaret Atwood: How technology is reviving old styles of storytelling

Or, even more strikingly, when Nault depicted Offred’s nighttime memories and the weight of her fears. As she wanders a garden during the story’s climax, terrified at the imminent prospect of becoming “a wingless angel”—hanged, like other enemies of the state, from a hook on the high wall that surrounds the commanders’ enclave—drooping red flowers in one panel become tiny, hanged handmaids in the next.

Questions about meshing her style with the Handmaid project never entered Nault’s mind, though, when Atwood’s publisher McClelland & Stewart sent out inquiries to a few graphic artists in 2015, seeking pitches and samples. Nault, who was in kindergarten when The Handmaid’s Tale was first published, has admired the novel since she studied it in high school. “It’s always seemed very contemporary to me. It’s really eerie how it seems to fit whatever times in which you’re reading it, always something that makes you think, ‘That’s just like now.’ That is one reason I was very generic with any technology pictured, like computers or phones or cars, trying to keep away from an ’80s period piece.”

So Nault was thrilled when “Margaret chose mine out of all of them,” and author and artist began a series of conversations “about her intentions when she wrote the book and which details to emphasize or change a little bit or could be cut out, because a graphic novel has a lot less space for words.” Nault made what she calls a “movie-style” script, which described each page and what it would look like, “because a comic-style script is not very evocative for people who don’t read them all the time.” It was a long-term, emotionally draining commitment, given her antipathy for Gilead—“I know some artists can maintain a little more distance between themselves and their work but I really can’t”—made all the longer when, halfway through, Nault hurt her wrist. “That’s about the worst injury you can get as a comic artist,” she wryly comments. “Why didn’t I just break my leg?”

READ MORE: An explosive gender revolution is under way. So why isn’t it changing anything?

Nault finished her work almost a year ago, and now that publishing’s slow-turning wheel has finally arrived at its March 26 release day, she’s poised between impatience and caution. “I’m bracing myself. I know there’s going to be some disagreement with how I interpreted things because there always is with such a beloved book, and because there’s also the TV show.” She has avoided the television version “because I definitely would have been influenced by its ideas—I couldn’t have helped it.” But Nault is well aware that “people love that show, and I think a lot of them are going to be expecting to see an adaptation of it rather than of the novel.”

Besides finally being able to binge-watch the TV episodes, Nault has something else to look forward to. In September, two months before her 80th birthday and 35 years after The Handmaid’s Tale first appeared, Atwood will release a sequel, The Testaments. Nothing is publicly known about the new novel other than it is set 15 years after Offred literally steps into the unknown—into a van driven either by saviours or executioners—and that the woman on its cover is dressed in green. Like millions of other fans, Nault has hope for Offred’s future, but she has little faith in a happy ending. “There are definitely things I want to see have happened, but really, knowing Margaret, it’s just going to go off in a totally different direction.”