‘I think that my father murdered my mother.’

Jeff Blackstock unravels the story of his mother’s death in the 1950s and lays it in the hands of his father, who at the time was a Canadian diplomat

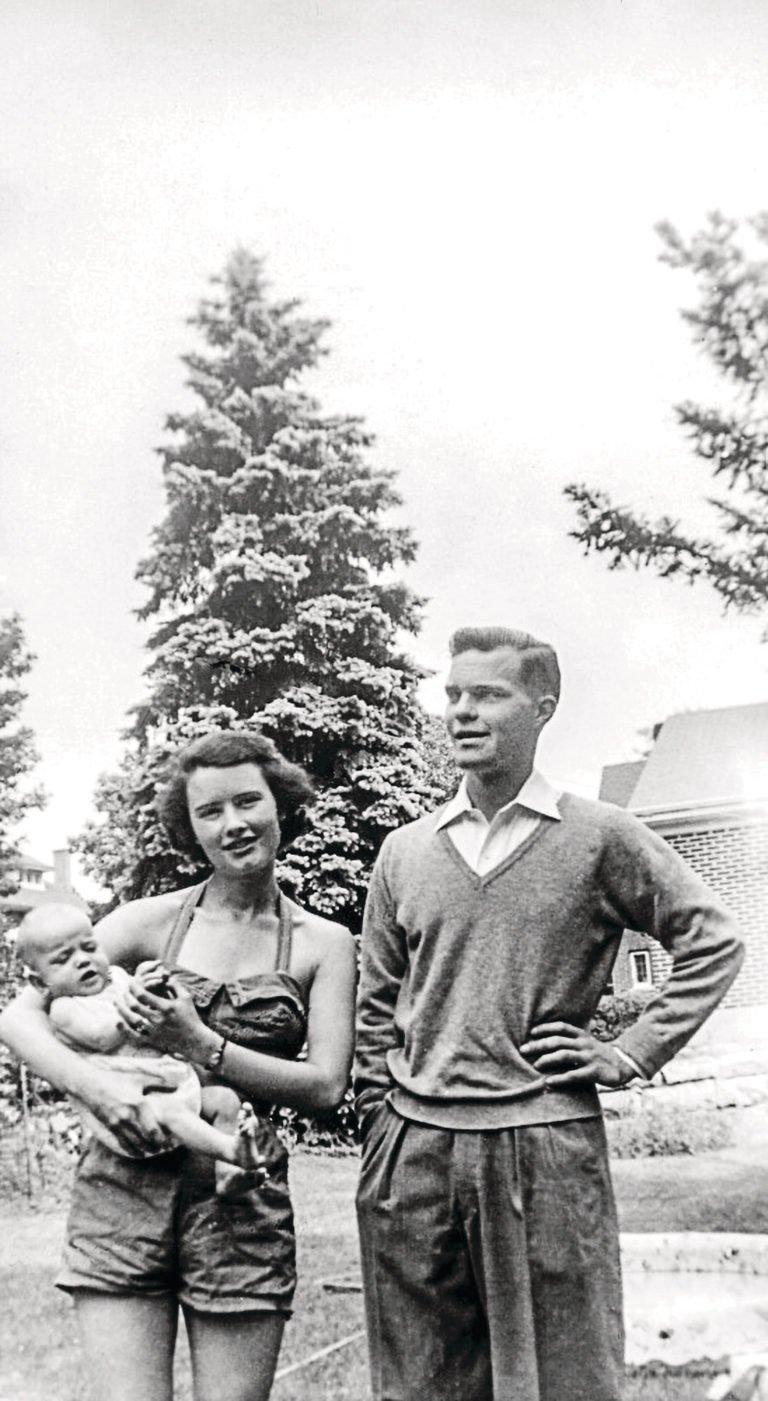

Carol and George with baby Jeff in 1951 (Courtesy of Penguin Random House Canada)

Share

It came as a profound shock yet no real surprise, Jeff Blackstock allows, when he learned in 1979 how his mother had died 20 years earlier. He was in London, Ont., and in his first year of law school when his sister, Julia, called from her home in Kingston, Ont. She told him about the autopsy report she had found among papers belonging to their recently deceased relative: Carol Blackstock had died of arsenic poisoning. “I ran from the telephone to throw up in the washroom,” he says in an interview, “and when I got back on the line, we both, at the same time, said, ‘Dad.’ We both already knew.”

So does anyone who reads the upcoming book Murder in the Family, which begins, “I think that my father murdered my mother.” In it, Blackstock, a 69-year-old retired Canadian diplomat, presents—in the meticulous language of his profession—a convincing account of how and why his mother died, who was responsible for the murder and who acted as “my father’s enablers” in keeping the crime buried. “I knew following this through could have consumed my life, I knew my mother would have wanted us to have carried on with our lives,” says Blackstock. “And I still knew I would have to write about it someday.”

The roots of Carol’s horrible death run deep. Jeff’s parents, Carol Gray and George Blackstock, came from very different worlds. The Grays, his beloved maternal grandparents and their only child, were comfortable by the end of the Second World War. They were happily ensconced in a Toronto apartment while father Howard, a Great War veteran and a working-class night-school graduate, worked as an accountant. The Blackstocks, for their part, were Upper Canada elite, descended from immigrants to Ontario in the 1830s who grew rich from becoming professionals, and from the liquor trade. One, after whom the town of Blackstock, Ont., is named, was counsel to the Canadian Pacific Railway and a close ally of Sir John A. Macdonald. Later, Jeff’s great-grandfather married into the Gooderham distillery family, and then went into business with his father-in-law as a partner in the Bank of Toronto, a forerunner of TD Bank. His son, Jeff’s grandfather, was a graduate of Upper Canada College (UCC) and the Royal Military College, and a highly decorated officer during the First World War.

The Blackstocks continued to flourish in the 1920s, a good decade for any family that derived its income from mining investments and alcohol. Times were harder once the Great Depression hit, and after Lt.-Col. Blackstock died young of a heart attack in 1945. Still, his widow could afford to live in a six-bedroom house in one of Toronto’s wealthier neighbourhoods, there was a family trust fund and summer estate north of Toronto, and Jeff’s father, George (born in 1933), was still able to attend UCC. There he made lifelong connections, including Ted Rogers, founder of Rogers Communications and godfather to Jeff’s younger brother, Doug.

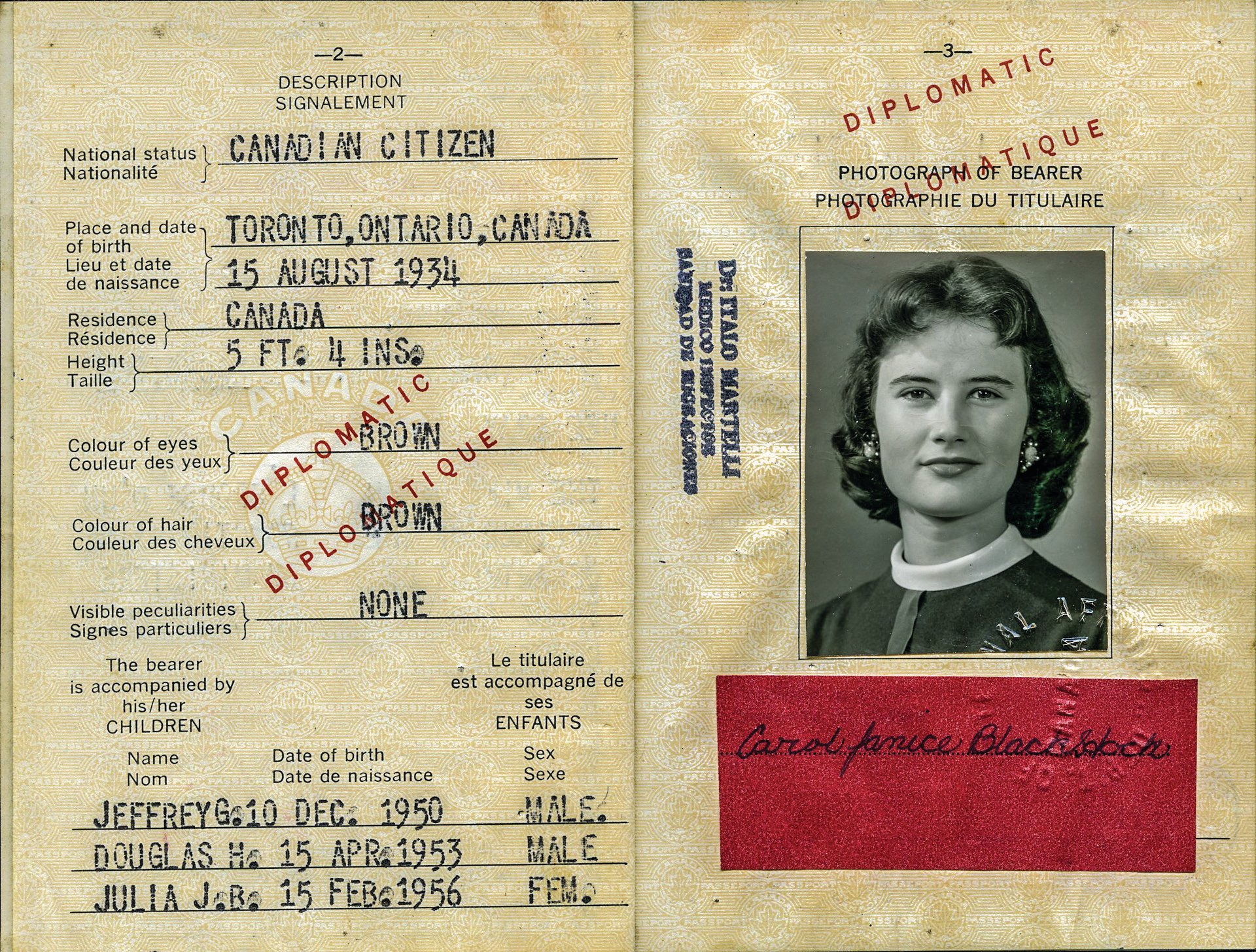

Then George met Carol, and by the spring of 1950, the highly intelligent, pretty, vivacious 15-year-old was pregnant with Jeff. She and 17-year-old George had their shotgun wedding before a justice of the peace in a Toronto suburb, far from the bridesmaids, bouquets and midtown Anglican ceremony that graced other Blackstock nuptials. A few hard years followed, marked by tense relations with in-laws George despised for their lower social status, and testy correspondence from great-uncle Brooke Bell, a high-powered Bay Street lawyer who doled out money from the Blackstock family trust. Things began to look up after George secured a job with the expanding postwar federal government, and more so in 1957, when he aced the foreign service exam and was assigned to the Canadian embassy in Argentina. In April 1958, the family arrived in Buenos Aires. The following April, days before George’s 26th birthday, Carol fell ill.

It was mysterious from the beginning, and became terrifying. There was endless vomiting and loss of feeling in her extremities, classic poisoning symptoms. Carol was admitted to a clinic where the attending physician, a devotee of mid-20th-century Freudian thinking, was convinced her ailment was psychosomatic and never checked her for toxins. As her symptoms waned at the clinic and—after a pause—waxed at home, she was in and out of the clinic, slowly shrinking from 115 lb. to an emaciated 90 lb. By July, Carol’s doctor suggested she return to Canada for treatment—pressure from an alarmed Ottawa bureaucracy roused into action by her parents probably contributed to that decision (George had never reported her illness to his superiors).

Her husband insisted Ottawa not tell the Grays he was bringing his wife to Montreal for treatment, and then took her on a 36-hour flight, which included a 90-minute stop in Toronto. Carol lay on her stretcher at the airport while her parents, who had no idea she was a short drive away, continued their frantic preparations for a flight to Argentina they could barely afford. On July 25, 1959, less than three days after she arrived in Montreal, 24-year-old Carol Blackstock died. Her baffled doctors performed an autopsy, but George nonetheless moved quickly: Carol died on a Saturday, was autopsied on Monday, was transported to Toronto on Tuesday and was laid in her grave on Wednesday. And then George ground to a halt, remaining in Canada for seven weeks before returning to Buenos Aires in late September to tell his children—Jeff, Doug and Julia, who were then ages eight, six and three, respectively—that their mother wasn’t coming back.

READ: Barry and Honey Sherman murder’s newest twist: family and police join forces

Less than eight months later, he was engaged to his second wife—Jeff Blackstock calls her Ingrid. George ever after claimed not to have met her during Carol’s lifetime, just as he claimed for the next two decades that no cause had ever been established for his first wife’s death, changing that story after the 1979 revelation to a claim no one had ever told him.

Jeff demolishes his father’s lies. There is correspondence from Ingrid that indicates George knew her long before Carol’s death. And while the official toxicology report—which found “significantly large doses” of arsenic in Carol’s liver, kidneys, brain, small intestine and even her toenails—wasn’t issued until the day after George returned to Argentina, the preliminary autopsy findings were enough to keep him in Canada for those seven weeks. The police had warned him not to leave. “He was interrogated more than once, and quite aggressively, according to an older cousin who was present,” says Jeff. “My sister and I have been trying to get the police records for years and are continuing to do so.”

Throughout the children’s confrontations with their father between 1979 and George’s death in 2007, they never raised the question of motive. It’s the same in Murder in the Family , even as Blackstock’s relentless presentation of facts points to two really good motives. Asked why he took that approach, Jeff replies, “I wanted to let my father speak for himself in those notes we found after his death.” In them, George is evidently crafting a defence against all charges. “He raises the issue of motive himself,” Jeff continues, “and writes in effect: Why would I have done this? The only reason that J and J—that would be Jeff and Julia, my sister and I—could possibly think of would be Ingrid. But we never spoke about that with my father at all. That came out of his mind.”

Clearing the path to marrying Ingrid, in an era when divorce could have been a crippling social, career and financial blow to him, made for an obvious motive. Far more subtly, Jeff’s account offers a motive for that motive, a deeper reason for taking up with Ingrid at all: George’s festering resentment of Carol. The shotgun wedding and the reality of her modest socio-economic status grated on him. Then George met Ingrid: the right age, the right social standing, the right family wealth—her father was a German industrialist and postwar immigrant to Argentina. “That conclusion is in the eye of the beholder,” Jeff says. “I leave that to readers.”

Something else he leaves to readers is almost as appalling as the crime—the silence from authorities, both Canadian and Argentinian, that followed it. “We are getting into speculation here,” says a cautious Jeff about his and his father’s former employer. “We’ve tried to get records from the government. Julia made multiple access-to-information requests back in the ’90s, which always came back empty, no records to be found . . . [Yet] we also know, from my sister’s interview with the pathologist who conducted the autopsy on our mother, that he was preparing for a criminal case, before it all of a sudden went away.”

Blackstock writes at length about how an investigation of a transjurisdictional crime would have required requesting the co-operation of the Argentinian government and the involvement of the Buenos Aires police, and could not have avoided scandalous publicity. Once again, Murder in the Family lays out facts but leaves the conclusion unspoken.

The federal government’s silence reminds Jeff Blackstock of his extended family’s, and his own. “My mom’s father was torn between loyalty to his daughter and burdening me with the knowledge. He did try to tell me when I was a teenager, but I wasn’t ready to listen. So he left us his papers. I think Blackstock family members, in their collective denial that something was very wrong, were conflicted as well.” In the end, as his grandfather came to believe, it would be up to Carol’s children to bear witness to her fate. And her oldest son has met that call.

This article appears in print in the August 2020 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “Father. Diplomat. Murderer?” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.