What the slumping economy is doing to Ottawa’s bottom line

With no federal budget we don’t know what the changes in the economic situation are doing to the government’s bottom line, but we can guess

Share

The 2014-15 fiscal year ends on March 31, and we still haven’t heard the government’s budget plan for 2015-16. Having a late budget is rare, but not unprecedented. Still, many Canadians might be getting curious about how the budget outlook has changed since the fall fiscal update from November showed budgetary surpluses for 2015-16 and into the future.

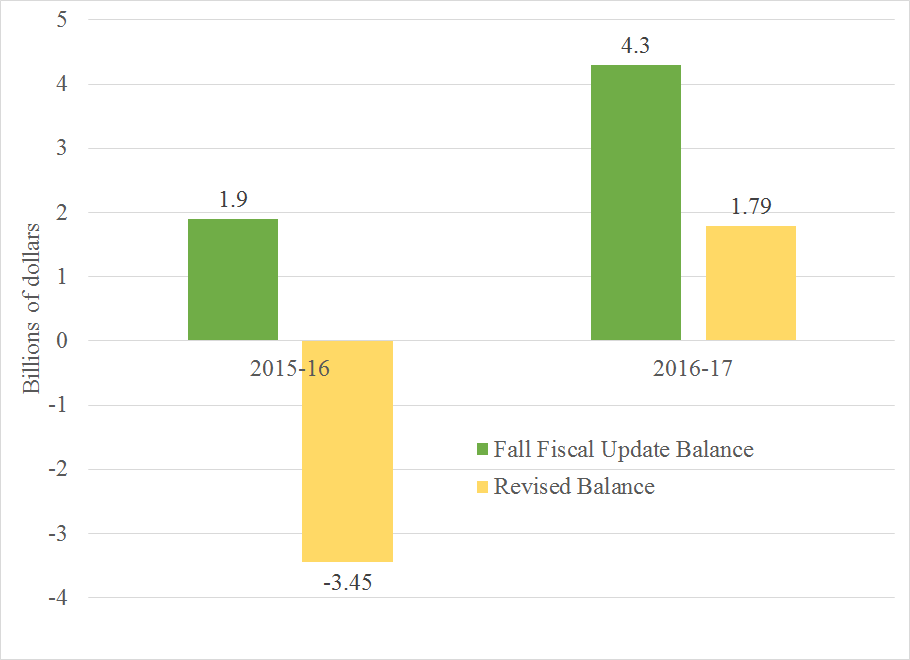

On Tuesday, TD Economics released its quarterly economic forecast containing projections for the economy over the next two years. If we take TD’s new economic forecasts and apply them to the data from the fall fiscal update, we can figure out how the federal budget position has changed over the last four months since Finance Minister Joe Oliver last provided some estimates.

We can do these calculations because the fall fiscal update provides a handy set of tables that tell us the sensitivity of the federal-budget bottom line to changes in the economic situation. If real inflation-adjusted economic growth comes in lower than forecast, Employment Insurance spending goes up, and tax revenue goes down. If inflation comes in lower than expected, revenues go down because the tax system’s thresholds and amounts have already been fixed for the year and lower inflation means less income in the higher tax brackets. For changes in interest rates, the impact takes longer to hit the budget, because it takes years for outstanding debt to be rolled over and start reflecting the new interest rates.

I’ve put together an analysis of the budget situation in light of TD’s forecasts, with links and notes about the assumptions I made. Four main lessons come out of the analysis.

First, if TD is right about the magnitude of the growth slowdown we’re experiencing, the net impact on the federal budget for 2015-16 is not huge—around $5 billion. While that’s manageable with some small adjustments for a federal government that collects and spends about $300 billion per year, it does push the balance slightly into deficit territory, unless Oliver takes action in his budget when he presents it.

Second, it’s the inflation numbers that are driving the bottom-line changes to the budget. TD is projecting GDP inflation to come in for 2015 at -0.6 per cent. This changes the budget balance, because the tax threshold and credit levels have already been set for 2015, and lower inflation means that fewer dollars “creep” over these fixed thresholds. The inflation change accounts for about 80 per cent of the $5-billion overall change in budget balance.

Third, the lower interest rates don’t matter much. It is true that the government will save money on its outstanding debt if lower interest rates stick around, but only about 18 per cent of federal debt turns over in a given year, so lower interest rates will take time to be felt. Moreover, the government actually holds a significant amount of interest-bearing assets and lower interest rates end up decreasing the revenue from those assets.

Fourth, if TD is right in its forecasts, the impact on the budget should be confined mostly to 2015. TD projects a rebound in real GDP growth and inflation in 2016, which would return the federal budget close to its originally forecast path.

Of course, if the economic outlook changes (either to the upside or downside), then these fiscal projections will change, as well. Next week, we begin spending money for the 2015-16 fiscal year. As those dollars are spent, it will become more challenging for Minister Oliver to adjust course for 2015-16, if there should be further shocks to the economic forecast.

(My disclosure statement is here.)