This is how Canada’s housing correction begins

Canadians are finally getting a taste of what a world with rising interest rates will look like, and one thing is painfully clear: we’re not ready for what happens next

Tighter mortgage rules, combined with rising interest rates, means it’s getting harder for people to obtain the large mortgages necessary to get into the market. (Photo Illustration by Ed Freeman/Getty Images)

Share

Kirk Marsh first noticed the mood start to turn in Vancouver’s housing market a year ago. As a real estate investor who buys homes and condos then fixes them up for resale, Marsh has an excellent vantage point on the market. Since giving up his old job in tech three years ago to flip real estate—“Sitting at a desk was killing me,” he says—Marsh has bought and sold six detached homes and condominiums across the B.C. Lower Mainland. “It’s not like TV shows where you see them making $100,000 or more each time, it’s just not like that,” he says. But he’s done well, always able to find buyers and come out ahead.

Or that’s how it used to be. “Today, everything has stalled,” he says.

While visiting open houses over the past year looking for his next flip, Marsh watched the frothing crowds and bidding wars steadily dwindle away. “There’s just nobody showing up at the open houses now,” he says. “Especially downtown. Usually you’d see a group of very aggressive people coming out.” But he’s also keenly aware of the slowdown because he’s trying to unload a renovated two-bedroom condo in New Westminster, just east of Vancouver. The unit, with an asking price of $569,000, had been sitting on the market for two months as of mid-December, with almost no interest.

Marsh is torn when it comes to the health of the market. On one hand, the strong local job market and inflow of new residents to the region lead him to believe the fundamentals remain strong for Vancouver real estate. But he also knows that Ottawa’s tighter mortgage rules, combined with relentlessly rising interest rates, means it’s getting harder for people to obtain the large mortgages necessary to get into the market: “I don’t know where the buyers are going to come from,” he admits. “And that worries me.”

He’s far from alone.

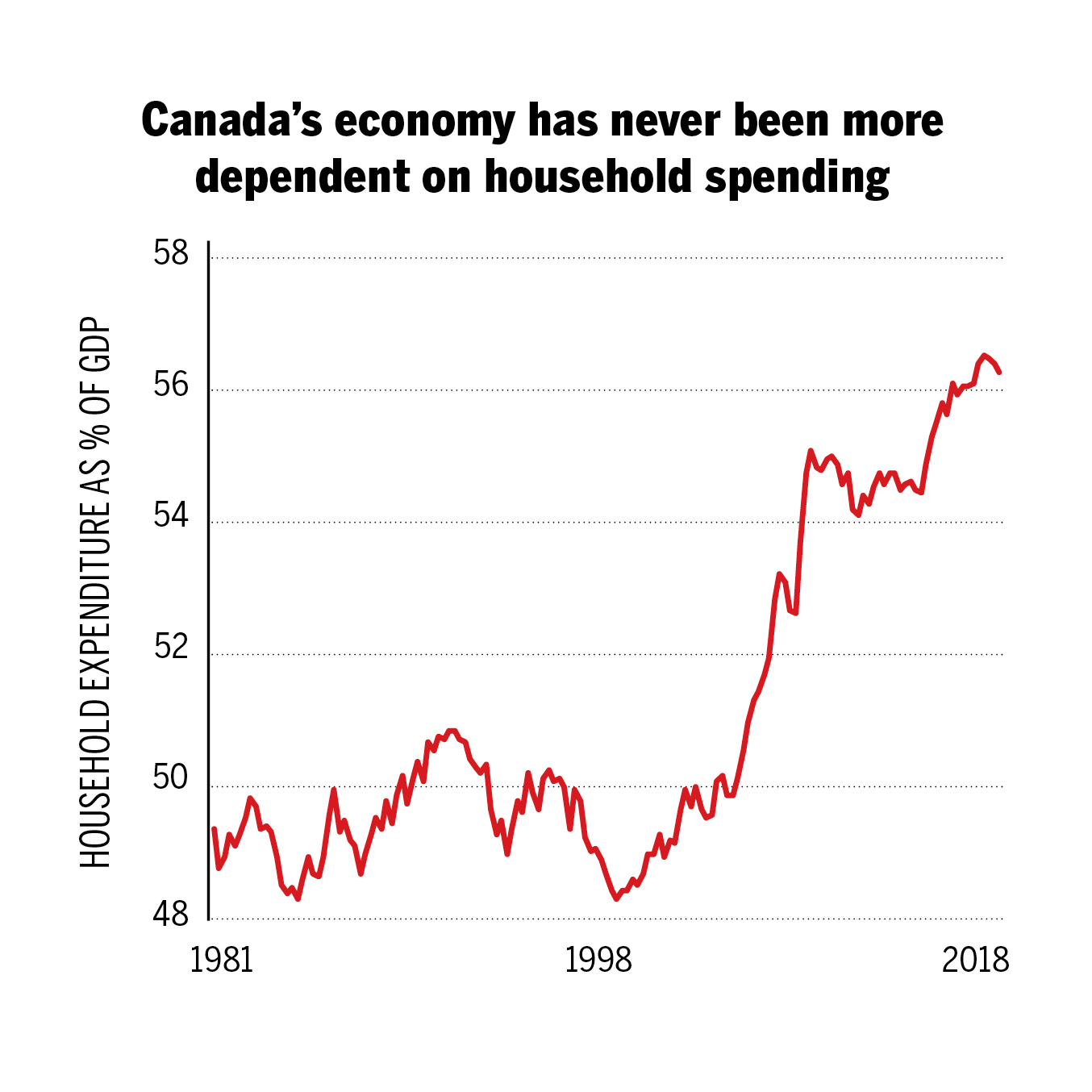

The willingness of consumers to borrow and spend—on houses, cars, furniture, restaurants, you name it—has been Canada’s primary economic engine for more than a decade. After Canada emerged from the Great Recession relatively unscathed, we were the envy of the world. Thank households for that. When turmoil and uncertainty held back business investment and crushed exports, Canada’s economy continued to grow while unemployment fell. Thank households for that, too.

It was plain to see what fuelled this consumption: cheap debt. Interest rates spent most of the past two decades going down and were at or near four-alarm emergency lows since the Great Recession. Canadians took their cue and gorged on debt. We now owe $2.16 trillion in mortgage, credit card and other consumer debt—an 80 per cent jump from 2008, and an amount that now exceeds the value of the entire Canadian economy. Even Americans didn’t go that overboard during their housing bubble.

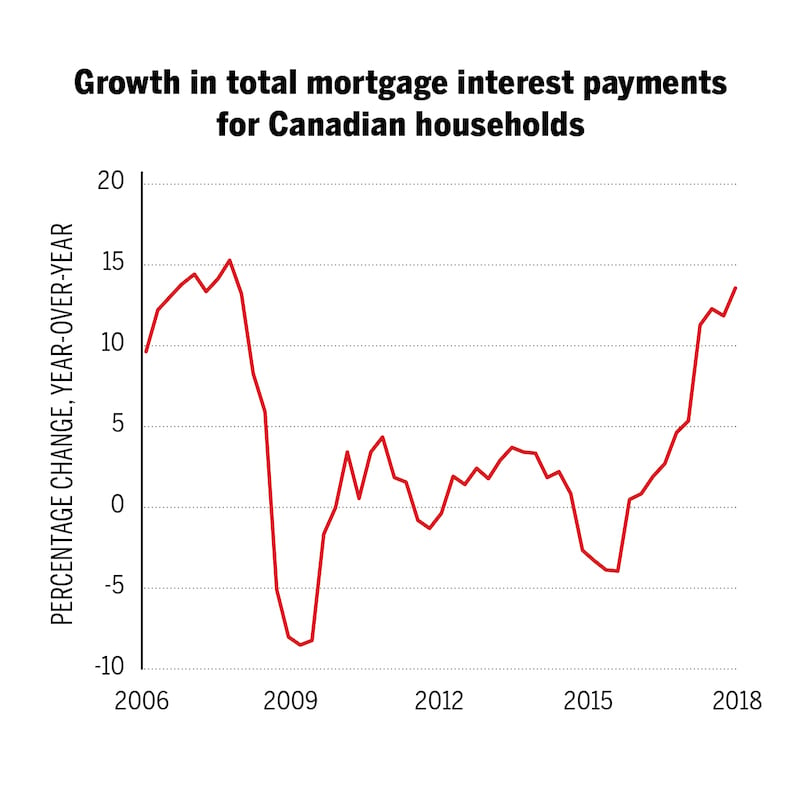

Now rates are rising, and many heavily indebted households are feeling crunched. In 2018, the Bank of Canada increased its benchmark rate three times to 1.75 per cent. Another two or three hikes are expected in 2019. For the first time in a quarter century, households are having to renew their mortgages at rates that are higher than when they first signed.

At the same time, the federal government has steadily tightened mortgage standards. Federally regulated lenders must put potential borrowers through stress tests, whether they’re applying for an insured or uninsured mortgage, to determine their ability to repay. The new mortgage rules have reduced the amount Canadians can afford to borrow by around 20 per cent, sending home sales tumbling across much of the country.

It’s a one-two punch that has shaken the foundations of the housing market, put an immediate dent in consumer spending and left economists and market observers wondering how deep the hit to the economy will be. “Maybe it’s just a moment and the market will rebound again like it has in the past, but maybe this is finally the perfect storm,” says Steve Saretsky, a Vancouver real estate agent. “I think we’re seeing the catalyst for a correction that everyone’s been talking about for 10 years.”

***

When the governor of the Bank of Canada stood to deliver a speech in Edmonton about his latest rate hike, the reception was frosty. While the goal of the hike was to cool an overheated economy, oil prices were sliding and households were already struggling to absorb a series of earlier increases. The governor stood firm: “It is not the bank’s job to be popular.”

While the current governor, Stephen Poloz, may share that conviction, the governor who delivered that speech was Gerald Bouey. The year was 1981, and in the span of just seven weeks, Bouey had cranked up rates seven times. His latest hike put the bank rate at a stunning 18.75 per cent. Yet Bouey wasn’t done. Rates would climb to 21 per cent as the bank strained to tame runaway inflation.

That era looms large in the minds of older Canadians. But a whole generation has grown up and entered the workforce and the house-hunting race never knowing a time when rates were above five per cent. The fact is that rates don’t have to rise to anywhere close to double-digit levels to create havoc with household finances, because households now carry so much more debt than they did then.

Each quarter, when StatsCan releases its closely watched household debt data, the most talked-about metric is always the debt-to-income figure, a measure of the amount of leverage the average Canadian carries relative to their disposable income. It steadily climbed in the post-recession era to 169 per cent—meaning households carried $1.69 in debt for each $1 of income—surpassing the debt-to-income peak reached in the U.S. before that country’s housing crash. Then in December came sobering news. StatsCan acknowledged it had overestimated the available income Canadians had with which to pay their debts. In one fell swoop, the debt-to-income ratio jumped to 173.8 per cent. And that’s just the national average. A recent report by Canada Mortgage and Housing Corp. (CMHC) revealed the debt-to-income ratio in Toronto stands at 208 per cent, and even higher in Vancouver, at 242 per cent.

Burdened with such massive debt loads, each incremental hike carries a heavier punch. And because rates are rising from such a low base, the impact of each hike on consumers is amplified. Canada’s interest rate might still seem low at 1.75 per cent, but households are now paying nearly 15 per cent more in interest payments on mortgages and consumer debt than they were just a year ago, according to StatsCan data. That’s the quickest pace that interest payments have grown since 2006, and it’s nearly 10 times faster than the post-recession average.

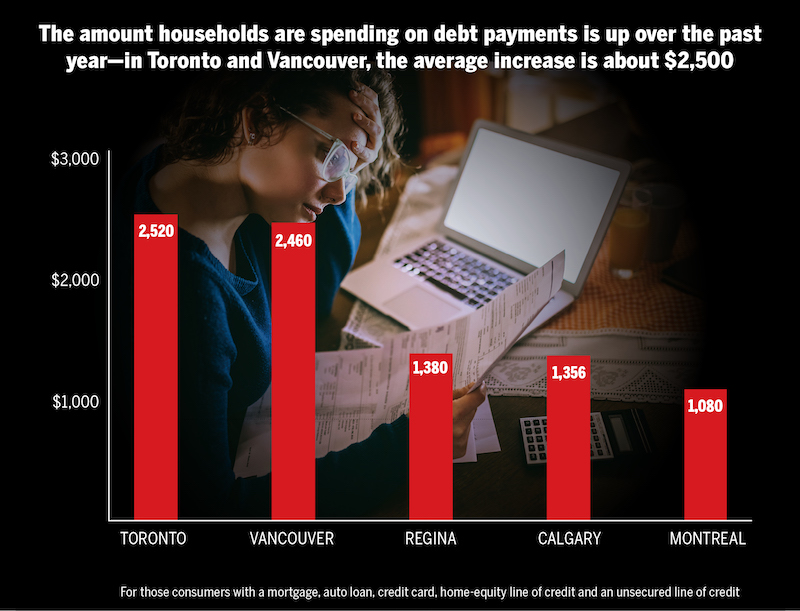

This is already translating into thousands of dollars in extra debt payments each year for households. In Toronto and Vancouver, the average monthly mortgage payment increased by $102 and $113 respectively from 2017 to 2018, according to CMHC data gathered from Equifax, the consumer debt rating agency. Now consider those households that also have auto loans, credit card debt and home-equity lines of credit. Their monthly debt obligations—defined as the minimum payment needed to avoid becoming delinquent—climbed by an average of $211 in Toronto and $214 in Vancouver. On an annual basis, that’s an additional $2,500 going toward debt repayment.

A survey last fall by Ipsos Canada on behalf of insolvency trustee MNP found one in three Canadians worry that rising rates could push them into bankruptcy. Yet so far, delinquency rates in most parts of the country have remained near their all-time lows. That’s because it can take several years for rising rates to be reflected in insolvency figures, says Scott Terrio, a consumer insolvency expert with Hoyes, Michalos & Associates. “When the credit cycle starts to turn, it’s like turning the Titanic,” he says. “Maybe that’s not the best analogy, but maybe it is. Going from the heady days of people getting as much credit as they want to possible recession takes several years.”

Terrio has a front-row seat to the process and says lenders are taking a tougher stance with borrowers than they were a few months ago. He’s started to see more clients come into the office who were rejected for consolidation loans by their banks, even though they’d been loyal customers for 30 years. Banks and other lenders are also going after customers more aggressively when they miss payments. One of Terrio’s recent clients saw the payments on her line of credit climb by $200 a month. It was enough to decimate her finances. “There’s a whole echelon of the Canadian middle class who have precarious incomes and live so close to the edge that $200 is a big deal,” he says. “There are a lot of homeowners in Canada who are asset rich but cash poor.”

***

After national house prices began to skyrocket in 2015—climbing 15 per cent annually and by as much as 30 to 40 per cent in some red-hot markets—regulators and governments scrambled to cool things down.

Poloz tried to jawbone households into coming to their senses, particularly those in Toronto and Vancouver. “In these two areas, we see a rate of price increase that would be very difficult to match up with any definition of fundamentals that you could point to,” he warned in 2016. “When people say, ‘Well, I need to buy a house because I’m worried that prices are going to go up this much again next year and I’ll be priced out of the market’ . . . In our opinion the fundamentals do not justify that kind of extrapolation.” If frantic homebuyers even heard Poloz over the din of bidding wars, they didn’t show it.

READ: The big losers of Toronto’s bursting real estate bubble

Less easy to ignore were a series of government measures brought in across the country. There were stricter capital requirements for mortgage lenders, foreign-buyer taxes in B.C. and Ontario and the city of Vancouver’s vacant-home tax, while the CMHC increased mortgage insurance premiums.

The biggest change, however, are tougher mortgage stress tests introduced in 2016 and 2017 by the federal government and the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions, Canada’s banking regulator, for both insured and uninsured mortgages. Now, regardless of the size of the down payment, borrowers must qualify at a higher rate than they’ll actually pay on their mortgage. In the case of uninsured mortgages, that is either the rate offered by the bank plus two per cent, or the five-year benchmark rate published by the Bank of Canada, whichever is higher.

The goal: to head off a potential financial crisis by making sure households carrying huge debts can keep making their payments when rates rise.

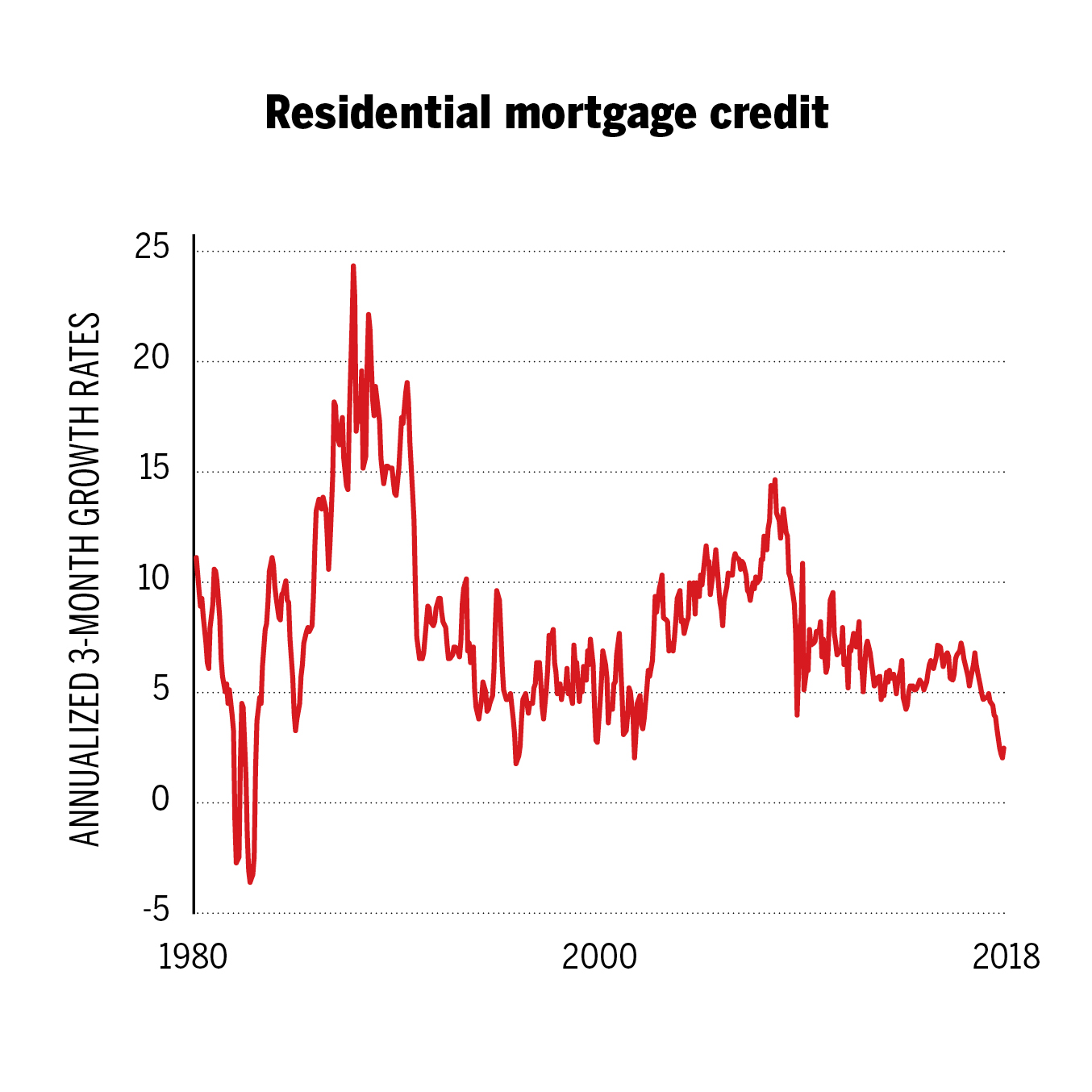

Whether it was the rule changes, rising interest rates or the inevitable demise of unsustainable real estate mania—or a combination of all three—housing markets are cooling. The pace with which Canadians are taking out mortgages has slowed to its lowest level since 2001. Meanwhile, the Canadian Real Estate Association reported in December that “national home sales are projected to post a double-digit decline in 2018, falling to the lowest level in five years despite supportive population and job growth.”

Certain parts of the country are getting hit harder than others. Croft Axsen, a mortgage broker in Calgary, a city still grappling with the fallout of the oil crash, doesn’t hide his frustration with the way tighter lending rules meant to cool Toronto and Vancouver are affecting his city. “We have 100 people a month who we’re telling we can’t get them a mortgage even though at any time in the past 30 years we’d have been able to,” he says.

Axsen lists off recent examples of clients who left empty-handed—a retired couple who rent and have $350,000 in savings but failed to qualify, or the self-employed homebuilder who made payments on a $1-million mortgage for five years but now only qualifies for a mortgage of $300,000. “[The government] is so self-righteously pompous about tapping the brakes on Vancouver and Toronto, yet other housing markets are now in recessions,” he says.

Wherever homeowners are, the new mortgage rules are likely to deliver an unpleasant surprise when it comes time for them to renew, says Ron Butler, a mortgage broker in Toronto. If a household keeps their mortgage with the original lender at renewal, they won’t be subject to a stress test on their finances. That’s not the case if they move their mortgage to another lender with a more favourable rate, even if no additional money is being borrowed. Butler estimates about a fifth of households trying to renew would fail the stress test if they tried to move their mortgage. These are typically younger households with very large mortgages and lower incomes, he says. Feeling trapped, more borrowers are staying put. “If you’re one out of five people, you’re paying more because of the interest rate increases, and you’re paying even more because of these rules,” he says.

As more households fail to qualify for mortgages from traditional lenders, some are turning to private lenders, which is adding a new dimension of risk to Canada’s housing market.

A recent analysis by the Bank of Canada showed that the quality of new federally regulated mortgages has improved since the tighter lending rules were put in place. In 2016, mortgages with a loan-to-income ratio of more than 450 per cent—meaning mortgages that are four and a half times greater than annual income—accounted for 21 per cent of all new mortgages. That share has now fallen to 6.2 per cent. The problem is that unregulated lenders have picked up the slack. The bank’s report found that roughly nine per cent of new mortgages in Toronto are now being signed with private lenders. Meanwhile, 20 per cent of refinancings in Toronto in the second quarter were with private lenders, a 67 per cent jump in just two years, according to research by Realosophy, a Toronto brokerage, and Teranet, which operates Ontario’s land registration system. Similar data isn’t available for other cities.

RELATED: Has ‘fixing’ Canada’s mortgage market made it riskier?

“That’s a huge red flag,” says John Pasalis, president of Realosophy. “Borrowers are going to these significantly more expensive lenders to take on more debt, largely to finance consumption, lifestyles they can’t afford and investment properties.”

Private lenders are considered lenders of last resort because they’re willing to take on riskier loans to homebuyers and homeowners who’ve been rejected by the banks. As such, they also get away with charging far higher rates—from seven to nine per cent for first mortgages and in the double digits for second mortgages. Private or shadow lenders also tend to go after delinquent borrowers more ruthlessly than the banks. And if there’s a slowdown, Pasalis says, private lenders are likely to pull back. “There’s nowhere for people to go after that,” he says. “If you can’t refinance your house, you have to sell.”

These pressures will not only keep a lid on house prices in Canada, but are likely to start dragging the market back down to earth as rate hikes take their full effect. And for an economy so dependent on household spending, that’s going to hurt. “We just went through a three-year period up until the middle of 2017 when every year everybody’s house was worth a lot more, so they felt wealthier and they spent,” says Butler. “Now that’s gone, and that wealth effect is being sucked out of the Canadian economy.”

***

Remember that additional $2,500 some households are now spending on debt payments each year? There’s another way to look at that: as $2,500 they are not spending on other things.

Many economists have been surprised by how quickly the impact from rate hikes has rippled through the economy. In a recent report, CIBC economist Royce Mendes notes it historically takes six quarters for the full effect of a rate hike to show up in slower spending. Yet it hadn’t been that long since Poloz’s first hike in July 2017 before the first pinch was felt. “The fact that the effects are showing up sooner this time around could simply be a sign that the storm will pass quicker,” Mendes writes. “But more likely it’s a reflection that models based on historical evidence will tend to underestimate the effects of rate hikes on the Canadian household sector in its current indebted state.” In other words, we’re in uncharted territory.

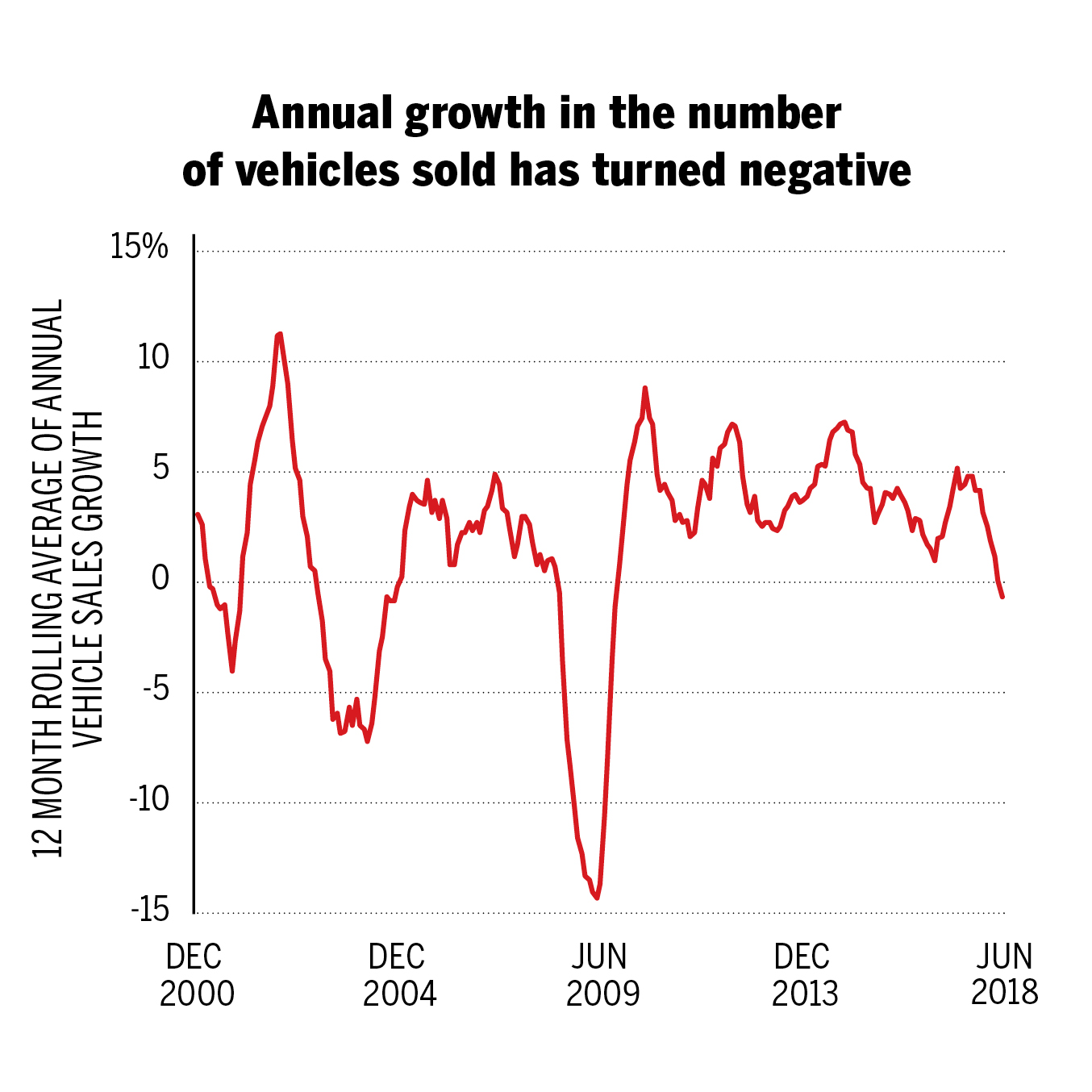

Consider, for example, the auto market. Canadians have always loved their cars and trucks, and thanks to the availability of cheap loans with 84-month terms, our tastes have grown more luxurious in the past few years. Elite brands like BMW, Mercedes and Lexus currently account for about 12 per cent of all vehicle sales. But dealerships are now seeing fewer customers walk through their doors. The number of vehicles sold in Canada outright shrank in October, compared to the year before. It marked the eighth straight month of declines, the longest stretch of negative sales since the Great Recession.

Mendes’s report notes that other retail sectors are also being hit much earlier than expected. Stores selling home electronics, appliances and building materials have all seen sales shrink. In November, Lowe’s said it is closing 31 underperforming stores in Canada, compared with 20 store closures across the entire U.S.

The one area of the economy that continues to hold up strong in the face of rising rates has been jobs. Unemployment in Canada sits at just 5.6 per cent, the lowest level since StatsCan began tracking it on a monthly basis in 1976. But even that looks precarious, given the slowdown in the housing market. Close to eight per cent of jobs in Canada are in the construction sector. In B.C., it’s nearly one in 10. Both are record highs dating back to the 1970s. If the slowdown in the real estate sector continues and the cranes start disappearing from city skylines, Canada’s job market could quickly start to look less rosy.

Well before that happens, we’re likely to see the job market hit as households put their budgets on an extreme diet. Terrio says homeowners will go to extreme lengths to avoid missing mortgage payments. In the past, that meant borrowing more. As that avenue closes, many will have to dramatically cut costs. A sudden pullback in consumer spending would lead to higher unemployment, which in turn takes what might be a managed soft landing for the housing market and turns it into a deeper correction or crash.

Will interest rates keep rising? Poloz warned Canadians in October to get used to the idea of three per cent interest rates. To get to that level, the bank would have to raise rates five more times. But Poloz has also taken a more dovish stance of late. “Getting there is a journey, and we expect over time to get there,” he said in mid-December. “But it can be interrupted, or it could be sped up, depending on how the economic data evolve.”

For his part, Ben Rabidoux, an independent analyst with North Cove Advisors, thinks the Bank of Canada has underestimated the hit to consumption and residential investment that’s coming, and for that reason, the bank is likely to be more cautious in the year ahead than it was even just a few months ago. “Those two things were nearly the entirety of Canada’s growth since the last recession,” he says. The problem for the bank, however, is that if the U.S. Federal Reserve keeps raising rates—as it did in December—and Canada doesn’t follow suit, the loonie could plunge. “You either decimate the currency or your rates rise in line with the U.S.,” he says. “That’s the nightmare scenario for the Bank of Canada.”

As for Butler, the mortgage broker, he offers what he calls his Mr. T prediction for Canada’s mortgage market in 2019. Echoing the mohawked actor playing Clubber Lang in Rocky III when asked his prediction about the upcoming fight, he says: “Pain. I predict pain.”