The man who shook Quebec

Jacques Duchesneau was hired to investigate corruption in the construction industry. No one liked what he found.

Jacques Duchesneau, leader of the Unite Permanante Anticorruption (UPAC), waits to testify during a parliamentary hearing at the National Assembly in Quebec City September 27, 2011. Duchesneau, also a former Montreal’s chief of police, investigated allegations of collusion to fix prices in government construction contracts. REUTERS/Mathieu Belanger (CANADA – Tags: POLITICS CRIME LAW BUSINESS)

Share

Montrealers can be forgiven for having been a tad restive during the sweltering first days of summer. There were the nightly student protests against Quebec Premier Jean Charest’s government and clashes with police. About a month ago, a six-metre-deep sinkhole opened up on Sherbrooke Street just hours after tens of thousands of protesters had walked past. In late June, a sewage pipe burst at rue Ste-Catherine and McGill College, revealing that one of the city’s busiest intersections was being largely held up by old tramway rails embedded in the asphalt. More sections of pipe promptly burst under Peel Street.

And then there were the perp walks by public officials. In May, Montreal’s former executive committee chairman, Frank Zampino, was hauled out of bed and arrested for his alleged part in the sale of city land to developer Frank Catania for a fraction of its value. Last week, Luigi Coretti, a close friend of former provincial Liberal cabinet minister Tony Tomassi, who himself faces fraud and breach-of-trust charges, was charged with fraud and fabricating false documents.

Protests. Crumbling infrastructure. Public officials in handcuffs. How much can one city be expected to take?

Quebec’s most powerful whistleblower

Yet if there’s any comfort for beleaguered Montrealers—and most Quebecers in general—it stems from work that took place in an unassuming, slate-gray skyscraper in downtown Montreal. It was in an office on the 16th floor of the 26-storey building that former Montreal police chief Jacques Duchesneau, as head of a government-appointed investigation unit, conducted an 18-month probe into the province’s construction industry and prepared what came to be known as the Duchesneau report. And it was in the same building that, over six days last month, Duchesneau testified in front of a commission into Quebec’s construction industry—best known as the Charbonneau commission, after its presiding judge, France Charbonneau—that was arguably created as a result of his own findings.

Duchesneau’s report and subsequent testimony threw open the door on the secretive and wildly lucrative world of Quebec’s construction sector. But while the revelations sent shock waves through Quebec, until now, few outside the province have heard much about Duchesneau and his stunning findings. As Duchesneau spoke with Maclean’s about his work, he shed light on the troubling signs of corruption in the industry, and what he sees as the Charest government’s efforts to stymie his investigation.

Related:

The report’s findings, first leaked to Radio-Canada’s investigative show Enquête last September, were jaw-dropping. Duchesneau detailed what he called “an entrenched, clandestine universe of an unheard-of size that is harmful to society in terms of security and the economy, as well as justice and democracy.” His report described how a tiny group of construction and engineering firms—“an oligarchy,” as Duchesneau put it to Maclean’s—managed to hoard the lion’s share of the province’s road construction projects just as the government, through a five-year plan launched in 2007, was committing $37.7 billion to the “modernization, repair and preservation of public infrastructures.”

The report further described how these firms have colluded with one another to rig the bidding system so that each gets a turn—with the others often hired as subcontractors. Another tactic is to drastically underbid on a job, then immediately ask for the maximum contingency funds allowed for in the contract. A haven for organized crime, Quebec’s construction industry is so rife with dirty money, the report said, that key parts of its supply chain were identified with the names of the gangs that controlled them. “A Hells Angels associate made it known that ‘everything that is asphalt in and around Montreal is ours,’ ” Duchesneau wrote. “[The associate] says how he recently acquired an asphalt company: a year after getting beaten, the owner decided to sell.”

Immense and awash in government money, Transports Québec has become the cash-generating and laundering outfit of choice for Quebec’s formidable organized crime network. “There are groups of general contractors who work as cartels, organizing to collude the tenders process to protect their members, eliminate competition and to get contracts at the price they want. Though they are legal themselves, some of these firms are have silent partners, thus increasing organized crime’s presence in the legal economy.”

As damning as it was, the report was eclipsed by Duchesneau’s testimony at the government corruption inquiry, which quickly established him as one of the most powerful whistle-blowers the province has ever seen. Imposing in presence and brutally forthright in his delivery, the former head of Montreal’s police service named names and told in exacting detail how billions of dollars of government money make their way into the pockets of a few individuals. He spoke of how many firms, by way of strategic (and, in Quebec, illegal) donations, helped run the election campaigns of certain municipal and provincial political parties. Nothing substantial in his testimony was challenged by government lawyers.

But perhaps most damning of all, Duchesneau said in his notes, recently presented as evidence during the Charbonneau commission, that at times he felt he was a pawn in the Charest government’s plan to obfuscate and stall the corruption dossier, and that members of the government were so bent on stifling his progress and smothering his report that he himself leaked it to the media so that it would see the light of day.

Jean Charest, it is safe to say, never wanted an inquiry into Quebec’s construction industry. Trouble was, just about everyone else did. The opposition Parti Québécois had been demanding an inquiry since September 2009, and according to a fall 2010 Leger Marketing poll, nearly 80 per cent of Quebecers wanted one. They were joined by a chorus of unions, Quebec’s Municipal Federation, legal and law enforcement groups and citizens’ organizations. The premier’s usual answer to the clamour was that the best way to tackle the problem was to leave it to investigators.

So, the government went to the police—or, in Duchesneau’s case, retired police. By the time Charest reversed his position in October 2011 to call an inquiry, the Liberal government had created Unité Anticollusion (UAC) and, later, the much larger Unité Permanente Anticorruption (UPAC), to root out corruption in the construction industry. Former public security minister Jacques Dupuis tapped Duchesneau to head up the UAC in early 2010. He was given a three-year mandate, after which he was to produce a report on his findings.

It’s not difficult to see why Duchesneau was chosen. A 30-year veteran of the Montreal police force, Duchesneau served as police chief from 1994 to 1998. In 1983, he arrested Henri Marchessault, his direct superior and a well-respected police officer, for stealing drugs from an evidence room. The arrest and fallout—many of his fellow officers were angered that he would do such a thing—has become Duchesneau’s “Serpico moment” and cemented his reputation for honesty and integrity. A recipient of the Order of Canada, the Order of Quebec and France’s Ordre national du Mérite, he was shortlisted to be secretary general of Interpol in 1999. “When I was a cop, I arrested all sorts of people, people who were doing things that ranged from stealing a bicycle to murder,” Duchesneau says. “ But people still had their story, and they knew that they had committed something wrong. The problem now is that these people think they are business people, but they are stealing our money. And no one is watching what they are doing. The ones who are supposed to be watching turn a blind eye.”

To some, at the time, his bona fides weren’t as important as his politics. “He’s a federalist, part of the gang,” says Stéphane Bédard, the Parti Québécois parliamentary leader. “He was associated with this government, and Charest was happy to name him?.?.?.?at first.”

Deconstructing the Quebec construction industry

During his testimony at the Charbonneau commission, Duchesneau illustrated publicly for the first time how specific companies would flout the bidding system to milk Quebec’s Transport Ministry. For example, Laval-based Doncar Construction was the lowest bidder on a construction contract with the Ministry of Transport. Once awarded the contract, Doncar promptly dropped out, and the contract then went to the second-lowest bidder, Les Constructions CJRB—which in turn subcontracted the work back to Doncar. The result: CJRB gets a higher price for the contract, and Doncar gets the work regardless.

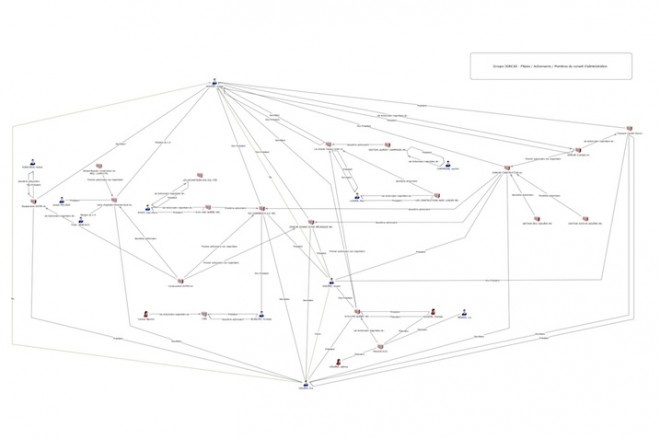

And, though the two companies are seemingly unrelated, Duchesneau’s team used a labyrinthine line chart to reveal that Doncar president Joseph Giguère and CJRB president Christian Blanchet are both vice-presidents in Les Carrières BGR, a quarry operating company that, as it turns out, shares the same address as Doncar Construction. (Giguère and Blanchet didn’t respond to interview requests. Duchesneau’s findings have not been proven in court.)

Click on the image below to see an enlarged version of the chart (opens a PDF):

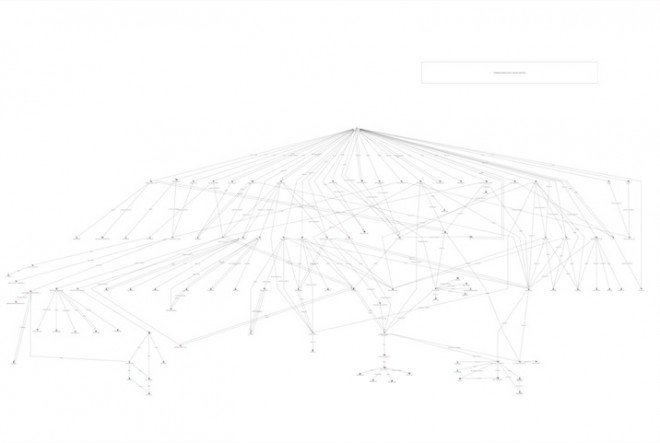

A second scheme uncovered by Duchesneau involved a company owned by Tony Accurso, arguably the most powerful and infamous figure in Quebec’s construction industry. Recently indicted on multiple fraud, conspiracy, influence peddling and breach of trust charges, Accurso oversees a construction and real estate empire. The Duchesneau team’s diagram of Accurso’s business interests, which bears a resemblance to the roof of Montreal’s Olympic Stadium, shows how the Laval-based businessman is president or majority shareholder in some 35 companies. In total, according to UAC numbers, Accurso and his children, Lisa and Jimmy, control 63 construction and real estate companies.

Click on the image below to see an enlarged version of the chart (opens a PDF):

“Someone in the [construction] field tried to have us believe that it was vertical integration,” Duchesneau testified, “But when we looked at it closely, you see [the structure] removes any chance of competition from anyone else. For example, if you and I are friends, I’ll sell you asphalt for $100 a ton. But if I don’t know you, I’ll sell for $110 a ton.”

Accurso certainly has friends in the industry. Through Simard Beaudry Construction Inc., the Laval-based businessman co-owns the asphalt company Usine Ashphalte Montréal Nord Inc. along with Construction Soter Inc., owned by Joseph and Eric Giguère of the Doncar fame. The relation speaks to a peculiarity of the Quebec construction industry: seven people are behind roughly 140 construction companies in the province, with ownership of certain companies shared amongst them. (Accurso also had friends in government: the recently-arrested former Montreal executive chairman Zampino had vacationed on Touch, Accurso’s Bahamas-based yacht.)

By virtue of the size and breadth, Accurso has essentially made himself indispensible. Even when Louisbourg and Simard-Beaudry pled guilty to tax evasion in 2010 and had their licenses suspended for four months as a result, Accurso was still able to put his fingerprints on work sites across the province. He simply bid for contracts through Louisbourg SBC, an ostensibly separate company with its own license with Quebec’s construction authority. The suspensions didn’t seem to hurt Accurso’ bottom line: according to an investigation by the Montreal Gazette, Accurso-owned companies accounted for some $270 million in city contracts between 2006 and 2011.

Duchesneau’s team also uncovered how Quebec’s ministry of transport was itself wholly unprepared to oversee the contracts it was handing out. A key part of the Charest government’s economic recovery plan, the MTQ will spend some $16 billion on roadwork construction between 2007 and 2012. The workload increase was seemingly at odds with another the Charest government ‘s plan to shrink the size of the province’s civil service: since 2003, the government has hired one civil servant for every two retirees. Though often applauded for lightening Quebec’s sizeable bureaucratic machine, the initiative limited the MTQ’s ability to oversee the worksites blooming across the province. (The MTQ stopped the ‘one-for-two’ program in March 2009.)

What’s more, Duchesneau says, many senior managers at the ministry have left to work for the engineering firms, and junior MTQ staff would often be charged with overseeing the work of their former bosses. “The guy that just left for the private sector wants to show that he has contacts and that he’ll do a good job, and the junior guy at the MTQ is so afraid of his former boss that he just lets things go,” Duchesneau says.

Like Accurso, these engineering firms have seemingly made themselves indispensible. As Sylvie Roy, an MNA with the right-leaning Coalition Avenir Québec, recently noted, the firms whose work was deemed “inappropriate” in a report following the crash of the 25-ton concrete slab onto the Ville Marie expressway last year recently secured a multi-million dollar government contract. SNC-Lavalin, Dessau and CIMA+, three of the province’s biggest engineering firms, will together share a $30-million contract to repair part of Montreal’s aging Turcot interchange, a major thoroughfare for truck and commuter traffic that at points is higher than the Ville-Marie is deep.

How things got political

As explosive as these allegations were, Duchesneau’s findings might never have come to light. Duchesneau testified that the government stymied his team. Within days of announcing his appointment, a deputy minister asked him to sign a paper swearing that he had no friends in organized crime. “I nearly fell on the floor,” he says. “When I saw that, I said, ‘Yeah, I have lots of friends in organized crime?.?.?.?So many, in fact, that many of them wanted to kill me.’ ”

It wasn’t just professional slights. Duchesneau said he had no budgetary control and no offices. “We had to squat in the deputy minister’s office,” he said during his testimony, recalling how he felt slighted by the very government that had appointed him. Duchesneau’s team of investigators had to use their own vehicles when visiting construction sites, creating a potential security risk. “In taking down the licence plate, well, obviously people could have figured out who we were,” he says. In May 2010, two months after he began work, Duchesneau aired his grievances in a 13-page letter to the Transportation Ministry, in which he asked: “Is the UAC but a facade to create a diversion to calm the 80 per cent of the population and 83 per cent of [Quebec’s] engineers who want a public inquiry into the construction industry?”

According to Duchesneau, then-transportation minister Sam Hamad had no interest in seeing the report when Duchesneau handed it to him last September. He recalls Hamad saying: “ ‘I don’t want to see it. My associates will take care of it.’ It was pretty disappointing, thank you very much.” For his part, Hamad, now minister of economic development, says he doesn’t remember the exchange.

Not long after he tabled his report to Hamad, Duchesneau gave a copy to Radio-Canada journalist Marie-Maude Denis. “Our team didn’t do the work so [the report] would go on a shelf, and after my meeting with minister Hamad, I was convinced that it was going to end up on a shelf,” Duchesneau testified later, admitting he broke his confidentiality agreement with the province.

On Sept. 6, five days after Duchesneau gave his report to Hamad, his team was essentially swallowed up by a much larger investigative body. Roughly a month later, after publicly criticizing the head of that squad, Robert Lafrenière, Duchesneau was dismissed—though it has hardly kept him quiet. He subsequently wrote a “volunteer report” about how the very structure of Quebec’s political system depends almost entirely on “dirty” money. And then came his explosive testimony last month.

During his cross-examination of Duchesneau, government lawyer Benoît Boucher didn’t challenge any substantial points of the former police chief’s testimony, concentrating instead on seemingly insignificant details. Boucher asked about his contract and his government benefits during his time as head of the investigative unit. “The only benefit I got was life insurance,” Duchesneau answered, locking his eyes on Boucher without blinking. “It could well have been beneficial.”

Later on, Boucher questioned Duchesneau on his use of the term “squatting” when referring to the UAC offices at René Lévesque and Beaver Hall Hill. It led to this odd exchange:

Boucher: And you had a bathroom?

Duchesneau: No, no…

Boucher: In the [deputy minister’s] suite?

Duchesneau: No, no, now…

Boucher: There was no bathroom in the suite?

Duchesneau: Yes, there was a bathroom in the deputy minister’s suite that I didn’t use.

Boucher: In the suite, there was a bathroom.

Duchesneau: Now we’re getting into details, don’t you think?

Duchesneau suggests the government had something to hide—and questions if he was set up to fail. “Why is it that we were given a three-year mandate? If we had accepted to abide by their rules, we would have given the report in late 2013, way past the election. They never saw us coming with a report after 18 months.” Yet because he produced (and subsequently leaked) the September 2011 report, the genie is out of the bottle; the Charbonneau commission, on hiatus for the summer, is scheduled to start again in mid-September, with testimony from key people in the industry.

The stakes are high for Jean Charest, who is seeking his fourth term in office. As it is, one of the companies targeted by Duchesneau’s team is Neilson-EBC, owned by the Fava family. Franco Fava, the family patriarch, is a long-time fundraiser for the Liberal Party of Quebec. Shaken by corruption allegations within his government, the premier faced an unyielding student protest over plans to increase tuition fees, as well as the law he put in place to stifle the protest itself.

For its part, the government says it supported Duchesneau throughout his time at UAC. Charest spokesperson Hugo D’Amours points out (rightly) that Duchesneau himself praised both Hamad’s predecessor Julie Boulet and successor Pierre Moreau. “We can’t pretend that the government put a stick in Mr. Duchesneau’s wheels,” D’Amours says, noting how Moreau has acted on Duchesneau’s recommendations.

Duchesneau wasn’t targeted by the government lawyer alone. At one point during her cross-examination, the lawyer for the Parti Québécois suggested Duchesneau chief had “hurt his credibility” by producing, after he was dismissed, what Duchesneau called “a volunteer report” into the illegal financing of political parties in Quebec.

“With no authorization, Mr. Duchesneau, pretended to be an investigator, gathered files on people and compromised the impartiality of his function as a representative of the state when he was head of the UAC,” said PQ lawyer Estelle Tremblay, who demanded to see a copy of the report. (It remains sealed.)

It was a surprising attack, given how PQ leader Pauline Marois has over the last nine months essentially used Duchesneau’s (official) report to hack away at the Charest government’s credibility. Duchesneau wonders whether the allegations contained in his report—among them, that as much as 70 per cent of the money used to fund political parties is “dirty”—might hurt the PQ as much as the Liberals. In an interview with Maclean’s, PQ MNA Stéphane Bédard dismissed Duchesneau’s suggestion along with his “volunteer report”—which Bédard called “that thing he did over a weekend.” “We have nothing to hide,” Bédard said, adding that he was “surprised” to hear Duchesneau attack the PQ. “If the PQ had something to hide we wouldn’t have been asking for a public inquiry for two and a half years.”

For all the attention, Duchesneau says he doesn’t plan to attend the hearings when they start up again in September. “I’m going on vacation, maybe to an iceberg somewhere in the North Atlantic,” he says. He thinks Quebec has heard enough from him, and he just might be right. Maybe his legacy speaks loudly enough already.