Kallisha Hoyes: The grocery worker on the pandemic’s front lines

Kallisha Hoyes found her job transformed into a suddenly essential, risky role: ‘Without us, no one’s eating’

Kallisha Hoyes. This portrait was taken in accordance with public health recommendations, taking all necessary steps to protect participants from COVID-19. (Photograph by Lucy Lu)

Share

Kallisha Hoyes gets up early. Really early. On a good day, the drive from her home in Shelburne, Ont., to Marc’s No Frills in Mississauga, Ont., takes an hour. And Hoyes, a front-end manager, likes to arrive before the grocery store opens at 8 a.m.

Wearing a mask she will keep on all day, she signs in to a system that now requires employees to log symptoms. While the aisles are quiet, she replenishes hand sanitizer and spray bottles full of disinfectant. She starts gathering items for customers’ online grocery orders. When the doors open, she supports customers and cashiers, sometimes running two lines at a time, using gloves to handle change.

When the gloves are off, Hoyes sanitizes her hands after touching just about anything. Door handles. Coffee cups. “My hands are cracking because I sanitize so often,” she says. “Everything I do, I’m overthinking it.”

The No Frills used to be quiet during weekdays, with so many customers chained to their desks. Not anymore. Now, the store is busy all the time. People seem to treat errands as an escape, a change of scenery. Hoyes gets it. While on maternity leave through the first couple of months of the pandemic, she’d often find an excuse to hit the grocery store after her husband got home. “I wanted to get out of the house.”

Hoyes prioritizes mental health, and is open about recovering from a period of depression. Still, the workplace is a stressful, risky environment from which she almost never takes a day off. Many colleagues quit, fearing the virus. The $2-an-hour “hero pay” top-up employees of Loblaw Companies (which owns No Frills) received during the first wave is a distant memory. There’s no word on vaccines. And Hoyes feels for non-unionized workers, whose jobs are even more precarious.

“Literally, we’ve been thrown into frontline work,” she says. “I don’t think it’s being acknowledged fully by the community, or even appreciated. Without us, no one’s eating, you know what I mean?”

Some customers won’t wear masks for medical reasons. Others, especially folks from a retirement residence next door, don’t wear them properly. Though Hoyes will occasionally get a heartfelt “thank you” as shoppers pass by, she and her co-workers more often bear the brunt of pandemic anxieties. A customer recently accused a cashier of racism for enforcing a limit on the amount of toilet paper they could buy. (The cashier was a person of colour.)

After her commute, Hoyes returns to her 19-month-old and 10-year-old sons exhausted. When she spoke to Maclean’s after getting home one day, she checked: “I’m at 17,000 steps.”

She showers right away and throws her clothes in the wash. When she has the energy, she takes the kids outside, has a glass of wine with her husband, sews masks for her side business or tries culinary trends from TikTok (she highly recommends the feta pasta recipe that recently went viral). But sometimes she just sleeps—“I’m telling myself it’s okay”—and rests up for the next early morning.

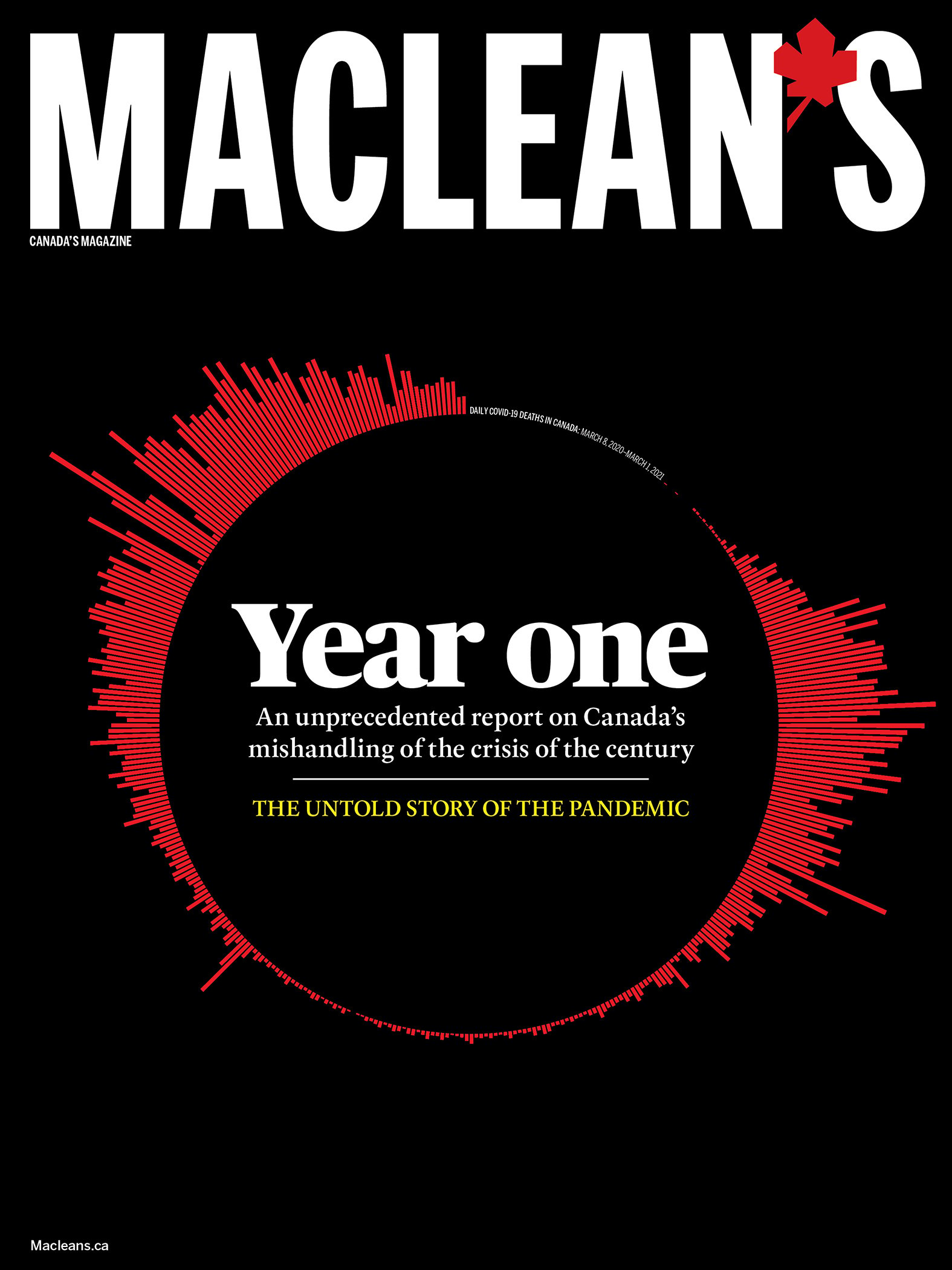

This profile appeared in the April 2021 issue of Maclean’s, where we gave our magazine over to a 22,000-word special report, “Year One: The untold story of the pandemic in Canada.” Sign up to read that whole story, and learn why we did it.