The Chateau Laurier fiasco exposes the idiocy of city amalgamations

Stephen Maher: The politicians who voted to let this happen represent people who have as much to do with the Laurier as people in Nova Scotia

A rendering of the proposed Château Laurier addition (LARCO)

Share

I live a five-minute walk from the Chateau Laurier, in Lowertown, a historic, charming, partially gentrified Ottawa neighbourhood with some rough edges.

One of the reasons I live here—where people are occasionally gunned down, and there are grim homelessness and addiction problems—is that I want to be able to walk to get where I am going.

When I walk to Parliament Hill, I can head through Major’s Hill Park, with the Chateau Laurier on one side of me and the Rideau Canal on the other, which I love.

My city government is going to wreck that.

Larco Investments, a British Columbia firm, has received municipal approval for an addition to the back of the Chateau that will destroy that beautiful space, putting a seven-storey brutalist wall at the end of the park, blocking the view of the romantic spires of the Chateau.

RELATED: The Chateau Laurier battle, and the risk of marring Ottawa’s historic core

When I think about what that addition will do to the Chateau, the park and the city, it gives me a queasy feeling in the pit of my stomach.

Nothing else the city government could do will ever have more impact on me than this decision, because it hits so close to home.

A lot of people feel the same way. Since it became clear last month that the city’s planning committee was going to let the project go ahead, people in Ottawa have been pressing their representatives on council to withdraw Larco’s planning permit. Councillors have been besieged by public input, the vast majority opposed to the addition as planned.

There is something mysterious about the council’s refusal to bend in the face of the biggest public outcry over a municipal issue in living memory.

When my councillor, Mathieu Fleury, managed to force a vote on Wednesday, Mayor Jim Watson and his supporters on council said that there is nothing to be done, because, after all, the developer owns the hotel, and if the city withdraws the planning permit, Larco could challenge the city in court, and then get to build the thing anyway, which, as Joanne Chianello explained, is nonsense.

I don’t know why Watson and his supporters won’t bend, but I know it is not for the reasons they say. I don’t even care. I only want to see their political careers end in ignominy when they next face the voters.

RELATED: Why Ottawa can’t have nice things

The problem that I have, and other voters who live near the Chateau have, is that I can’t vote against the people who made this happen.

The 10 councillors who voted against the addition live nearest to it, among people who are most likely to be affected by it because, for example, they might see it from time to time.

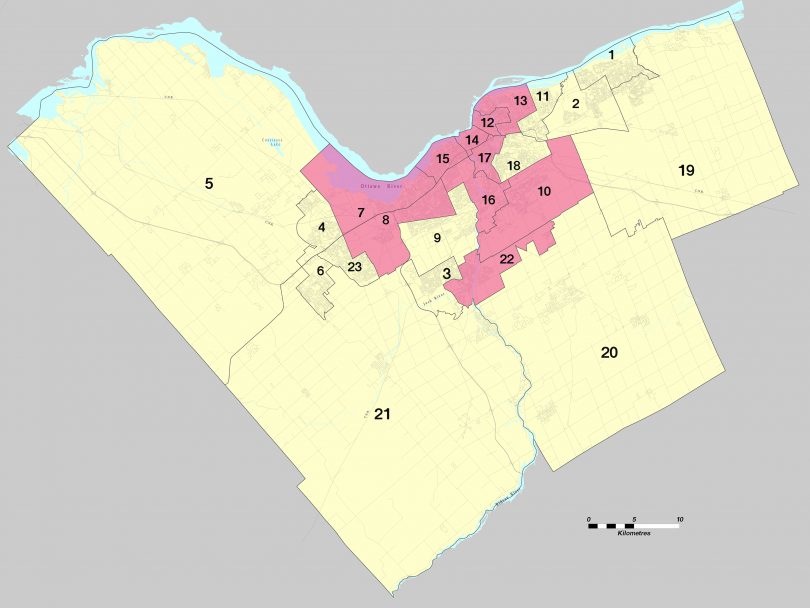

The 13 who lined up behind Watson represent rural and suburban voters who likely have other things on their mind (one councillor was absent). Nothing tells the story more clearly than a map of the city showing the wards of councillors who wanted to reconsider the project.

Thanks to former premier Mike Harris, who amalgamated Ottawa with nearby municipalities in 1999, Ottawa is huge, more than 2,790 square kilometres. From my home, it would take me about an hour to drive to the western, eastern or southern boundary, where I would find myself in fields and woods, where the people live in single-family detached homes and drive to work and the grocery store.

The councillors who gave earnest but misleading speeches about how their hands were tied—poor devils—represent people who have as much to do with the Chateau Laurier as people in Nova Scotia.

It’s maddening.

I don’t have any desire to play a role in the governance of Stittsville, for example, a suburban town of 33,870 on the outskirts of the city. Neither do I want the councillor from there deciding what should happen to the Chateau Laurier, in my backyard, but that councillor voted for the addition.

By forcing the amalgamation of Ottawa, Hamilton and Toronto as he did back in 1999, Harris gave the whip hand to suburban voters, which was likely his goal.

RELATED: Architect Peter Clewes on the Château Laurier expansion

Harris said that he wanted to do it to cut down on the number of municipal politicians, which is the same justification Doug Ford used to muck around with Toronto’s ward system before that city’s recent elections.

But amalgamation did not produce the promised cost savings, and we are left with unwieldy municipal governments, where suburban voters exercise power over the denser areas where most of the taxes are collected and where demands for services are higher.

In municipal power struggles, suburban voters have different priorities than people who live close to downtown. They tend to be more interested in highways than in transit, more pro-development and less inclined to take measures against the kind of sprawl that produces short-term profits but ends up imposing tax burdens on people who live in denser areas. They are less inclined to support the kind of social spending that seems sensible to people who live in urban areas, where we live daily with homelessness and street crime.

Suburban Toronto voters made Rob Ford mayor of Toronto. Suburban Ottawa voters elected councillors who are letting a developer destroy an Ottawa landmark.

This is not how our cities should be organized.

Suburban voters should run their own affairs and let city people do the same.