Vladimir Putin considers this Newfoundland man a ‘friend’

John Stuart Durrant, Russia’s east-coast honorary consul, will soon accept one of Moscow’s highest honours. In tense bilateral times, the longtime academic steers clear of politics

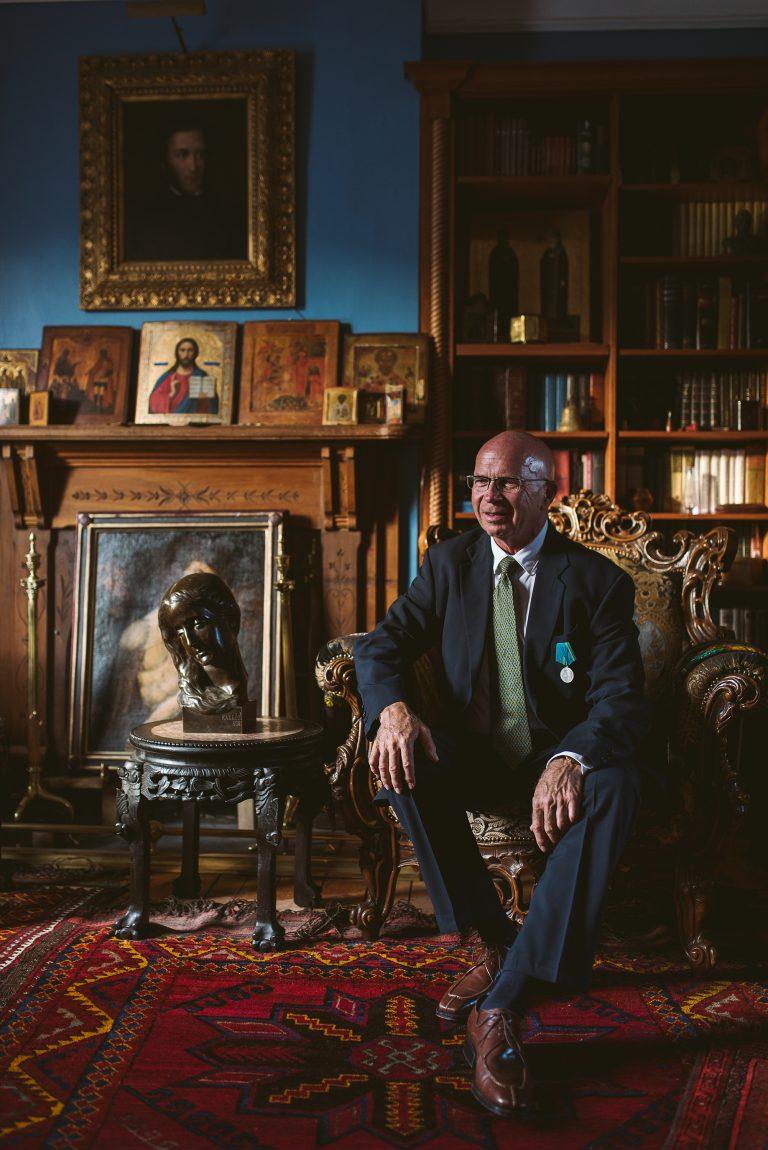

Durrant in his study at his home in St. John’s, Nfld. (Photograph by Alex Stead)

Share

It’s no small feat for John Stuart Durrant, a Canadian living in St. John’s, to be declared a friend of Russia by none other than President Vladimir Putin. After all, Canada’s foreign minister, a staunch ally of Ukraine, is banned from visiting Canada’s erstwhile Cold War foe. But Durrant is no Chrystia Freeland. As honorary consul to Russia, the academic has, for more than a decade, helped any Russian citizen who encounters trouble in Newfoundland and Labrador.

Durrant’s recent achievement of state-sanctioned kinship with Russia, in the form of the Order of Friendship Medal, caps decades of devotion to Canada’s northern neighbour. He was born and raised in southwestern Ontario, and was in high school when he first felt what he describes as “the gravitation.” He’d picked up a textbook at a library and was fascinated by the language within. Durrant wound his way through an undergrad at Western—in Russian and Spanish—before studying at the University of Warsaw in Poland, the University of London in the United Kingdom and, eventually, Lomonosov State University in Moscow. He came back to Canada with a Ph.D. in Russian literature and settled into academic life. He learned to speak seven languages and read another six.

A few years after completing his doctorate, Durrant applied for a job at Memorial University in St. John’s. He vividly remembers his flight to the interview in 1987. His father had recently died, he was late leaving for the East Coast and, when he reached Halifax, a blizzard had engulfed the Maritimes. He snagged a spot on a tiny plane with Brian Peckford, then Newfoundland’s premier. They flew to Corner Brook and lunched with a relative of a Peckford staffer along the way. “That was my introduction to the wonderful province of Newfoundland,” he says.

READ MORE: Parliament’s secret briefing from CSIS: Beware of Russian spies

In 2008, the Russians came calling. They asked Durrant if he’d serve as honorary consul, an apolitical role that involved promoting cultural exchanges and helping wayward Russians in need. He was soon accompanying Russian delegations on fact-finding missions around the Atlantic provinces as they researched institutional reform and queried Canadians on how their governments tick.

In 2011, for his “great contributions to the study and preservation of the Russian cultural heritage,” Russian president Dmitry Medvedev awarded Durrant the Pushkin medal, a high honour in arts and culture. This November, Durrant will likely visit Moscow—details are still being worked out—to receive an even higher state honour. The Order of Friendship medal is rarely bestowed on Canadians, reserved for the likes of former prime minister Jean Chrétien, a longtime promoter of Russian interests and a friend to Putin. Adrienne Clarkson and former senator Marcel Prud’homme have also received the award, which dates to 1994.

Chrétien’s ceremony was in Ottawa in 2014. Not long after, Canada-Russia relations cooled when Russia invaded and annexed Crimea, which for decades belonged to Ukraine. Ottawa has since slapped sanctions on dozens of Russian people and companies. Russia banned several Canadians, including Freeland, from setting foot on its soil. Stephen Harper famously told Putin to “get out of Ukraine” at a summit of world leaders, and early in his mandate Prime Minister Justin Trudeau reiterated to Putin that Canada stood firmly with the Ukrainians.

RELATED: Donald Trump made an offer that Ukraine couldn’t refuse

Durrant watched these events unfold from his perch on the Avalon Peninsula. Cultural exchanges have dried up. Fewer ships from Murmansk, a port in northern Russia, sail into St. John’s harbour. Durrant stays out of the politics, emphasizing the narrowness of his role as a consular official. But the chill is a shame, he says. “We share problems that are identical,” given our similar climates and terrain, he says. “Even our polar bears could have a conference on their problems.”

As Canada feuds with Russia about its expansionist policy, Durrant leans on the “larger cultural context” at the core of his expertise. “Politicians come and go. Political issues tend to fade as history evolves. Things lose their sharp colour sometimes, and their sharp edges,” he says. “It’s the lessons of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky which persist. They’re universal.”

Durrant politely scoffs at the Canada-Russia hockey rivalry as somehow binding the two nations. (He jokes that it’s the “lowest common denominator” of shared interests.) He points to St. John’s and Murmansk as strikingly similar port cities. He remarks on a student exchange trip where he witnessed Newfoundlanders and their Russian hosts, equally unpretentious, get along famously as American and British students struggled to bridge the culture. He ponders our shared riches in natural resources, our struggles with melting Arctic ice, and the cultural resemblance between Indigenous peoples in the north of both nations, and he sees only common ground.

“There’s all these strange connections between Canada and Russia that transcend hockey and that would help us if we knew more about each other,” he says. For Durrant, it all starts with friendship. And, of course, the medal to prove it.

This article appears in print in the October 2019 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “Moscow’s man in St. John’s.” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.

MORE ABOUT RUSSIA:

- The world has turned on Syrian refugees

- Can the world recover from Trump, Putin and the collapse of optimism?

- The Putin regime would love for Canada to hand over this dissident Russian scientist. Ottawa can’t let that happen

- When Trump phones a pal on an unsecured cell, won’t someone think of the spies?