Adventures in Afghanistan’s ‘Nothing Land’

A show about a fictional ministry of garbage pokes fun at Afghan politics—and shakes up the TV landscape

Ahmad Masood/Reuters

Share

The BBC’s famous mockumentary The Office has inspired numerous copycats since its inception in 2001. America’s NBC adaptation, which is about to start its eighth season, popularized actor Steve Carell’s socially inept character, Michael Scott, a paper company manager with a penchant for political incorrectness, sexual indiscretions and a fascination with Meryl Streep. More recent contemporaries are no different: most versions of comedian Ricky Gervais’s original Office production, from France’s Le Bureau to Quebec’s La Job, come complete with almost interchangeable office antics. Every version, that is, except one: an Afghan TV station, Tolo, aired its own Office-style series this summer called The Ministry, replacing office politics with real ones.

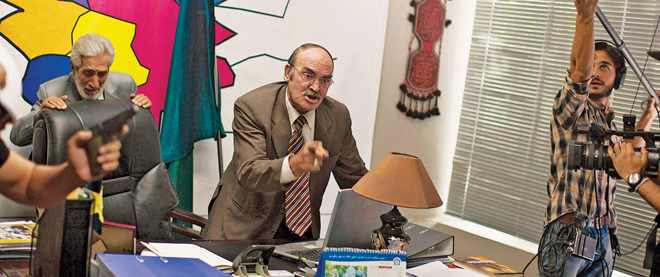

The eight-episode series (season two is set to air in October) takes place in a fictional country mirroring Afghanistan, called “Hechland” (translation from Dari: “Nothing Land”), and follows the shenanigans of Hechland’s Ministry of Garbage and its narcissistic minister, Dawlat—played by Abdul Qadir Farookh of the The Kite Runner. Farookh is one of the only actors with professional experience on the production—a Kabul apartment flat converted to a studio by the show’s producers. “Everyone on set is in training,” says 31-year-old Abazar Khayami, one of the show’s senior producers. “But we took our disadvantage and made it into an advantage.”

There is no official television rating system in Afghanistan, but Khayami says it’s obvious The Ministry is one of the most popular shows in the country, as its actors are frequently recognized on the streets and invited into politicians’ homes for dinner. The series’ plots range from government corruption and nepotism to gender inequality and suicide bombings. In one episode, Dawlat the minister (a former New York cab driver who earned his job through pure nepotism) pays off the wrong warlord, setting off a string of suicide bombings he was supposed to prevent. “Nothing is taboo,” says Khayami, noting that things would probably be very different if the show made fun of the Afghan government in a direct, rather than veiled way. “When they are alone in their homes,” he says of real-life government officials, “I like to think they watch the show and laugh. But if we had gone that extra inch and called it Afghanistan [instead of Hechland] and poked direct fun at the administration, then it might be a different story. We’ll never know.”

What Khayami does know, however, is the volume of problems that comes with filming a television show in a war-ravaged country. “You get there [the studio], sometimes the electricity goes off, jets are flying around, bombs going off, and then there’s the call to prayer three times a day.” But, surprising even himself, he doesn’t regret a single minute of it. A Hawaiian-born American of Iranian descent, Khayami never thought he would end up working and living in Afghanistan. In fact, he was employed by Warner Bros. in L.A. when the CEO of Moby Group (the Afghan media corporation that owns Tolo TV) offered him the job at The Ministry. “He told me to come over [to Afghanistan] and just take a look,” says Khayami, “and eventually I did.” And he hasn’t looked back: Khayami has been busy working on season two of the series to air next month, twice a week on what is arguably Afghanistan’s most popular television station (Tolo TV also runs Fox’s old hit drama Prison Break, along with several original Afghan dramas).

“Tolo” translates to “sunrise” or “dawn” in Afghanistan’s official languages, Pashto and Dari, symbolizing what the The Ministry’s creators hoped would become “a new era for Afghans.” Whether it’s fulfilled, that wish is certainly debatable; at least every injustice made light of on the show still retains its real-life presence in a country reeling from war. And that’s not funny in the least. But Khayami argues that even though his fictional regime hasn’t reformed Afghanistan’s real one, it’s at least opened people’s eyes “to the truths they already know are going on.” What’s more, it’s made them laugh in the process.