Are bed-bug bylaws a good idea?

Pest infestations are driving renters around the bend, but Toronto’s response might be harder on tenants’ finances than it is on the vermin

Christian Cadieux (R), owner of Bed Bugs Bite , and employee Jeff Lake fumigates a matress as part of their process to get rid of bedbugs. (Andrew Francis Wallace/Toronto Star/Getty Images)

Share

The two-bedroom apartment in the North York area of Toronto appears to have been ransacked. Cupboards are thrown open and emptied, dresser drawers are overturned on the floor, the mattress is stripped and flipped against the wall. “This is good prep,” says Ed Bandurka, a branch manager with Orkin Pest Control. “If she hadn’t done this, we wouldn’t be able to do our job today.”

The job he’s referring to is bed bug extermination, a multi-step process of vacuuming every nook and cranny of a resident’s furniture, hosing it with piping-hot steam to kill all bugs and eggs, and spraying a pesticide for good measure. It’s the biggest service Orkin provides in the GTA, mostly tending to calls from landlords of multi-residential buildings. Today, Bandurka and pest control technician Jamey Osmond will be treating three units the building—all repeat visits.

“Let’s have a look,” Osmond says, flicking on his flashlight to examine the corners of the wardrobe drawers, their light wood speckled with tiny black stains of digested blood. “Let’s see if we can find you something.”

“Bingo,” Bandurka declares from the other room where he’s studying the underside of the box spring. A cluster of what looks like tiny apple seeds is stuck together under a flap of fabric. The brownish black mass shows every life stage of bed bugs, from egg to nymph to the slightly larger adult. As we scan the apartment, it’s clear the bugs are thriving—on the bed, in the dressers, on the couch, and probably elsewhere. The tenant says she’s had them for close to a year. Leaving the bedroom, the unmistakable scuttle of a cockroach catches my eye. “They must have roaches too,” Bandurka says, nonchalant. A cursory glance at the kitchen confirms the hunch. Their droppings, pepper-like specs, are all over the counters and appliance, and a half dozen nymphs are feeding on grease on top of the oven. “Watch yourself,” Bandurka says, gesturing me to move aside as I stare, both disgusted and compelled, at the bugs. “You don’t want that guy falling on your head,” he says pointing to the roach crawling on the ceiling directly above me. “Is this a bad infestation?” I ask, assuming it’s an unusually unfortunate scenario. “Nah,” Osmond says. “On a scale of one to ten, I’d say it’s a three.”

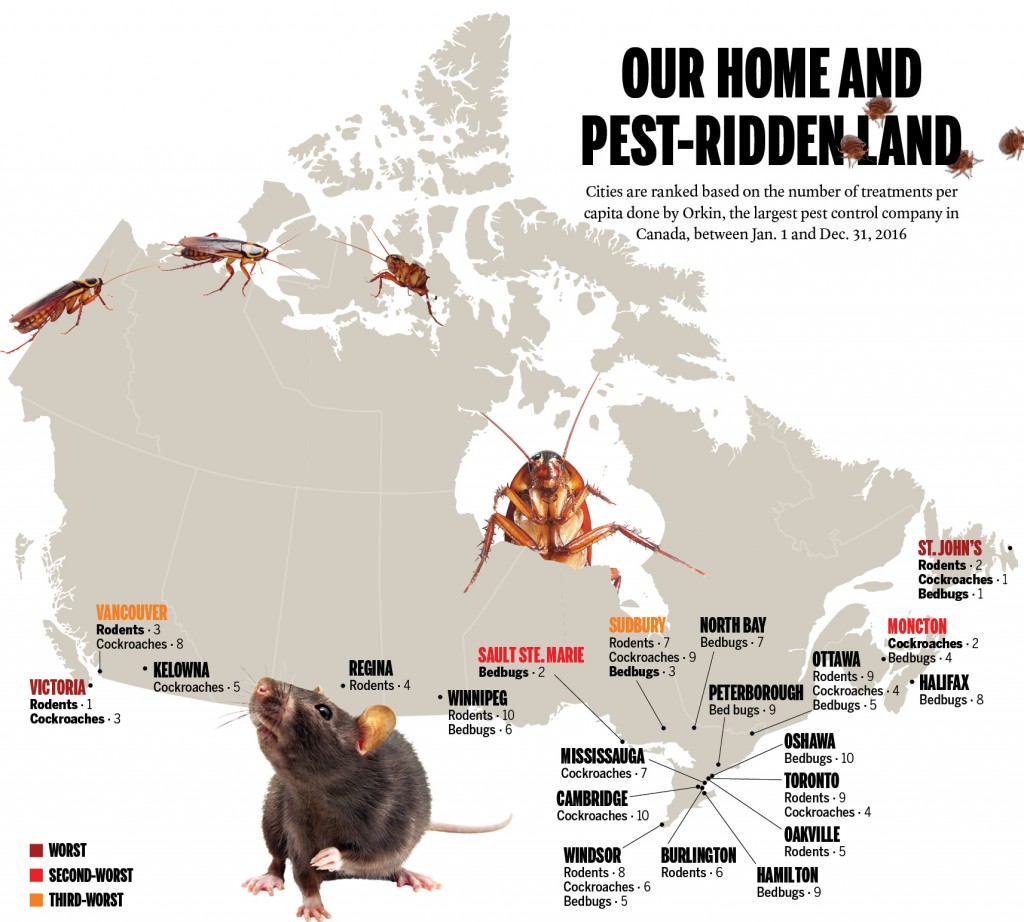

Pest problems across Canada are severe and widespread, particularly in urban rental stock. No matter how clean and careful you are, they’re not always avoidable. In Toronto, the city is about to implement a bylaw to help get the problem under control by proactively requiring landlords to implement pest control programs and prohibiting them from renting any unit that has pests, namely cockroaches, bedbugs and rodents.

The news comes as a victory to tenants unable to escape bugs and other vermin. The problem is, with the majority of rental units showing signs of infestations, cracking down on resilient pests in densifying metropolitan areas presents a dilemma. If the city is serious about withholding units showing any signs of pests, it means eliminating rental stock from a market that’s already tightly pinched. In Toronto for example, where the vacancy rate is about 1.3 per cent, the waitlist for affordable housing is pushing 100,000 units. Meanwhile, some estimates show that close to 83 per cent of low and middle-income tenants in the city have had cockroaches in their apartment, and 30 per cent have had bedbugs. Fully enforcing the sort of bylaw Toronto has passed would trigger a supply crisis in an oversubscribed market, while saddling landlords with extermination costs they’d likely pass on to tenants. In Toronto, rents are already sky-high. Temporarily condemning rental units that have pests would mean added strain on an already undersupplied market. On the other hand, any leniency with the bylaw, and pests will persist.

“Pest infestations are exceptionally common,” says Michael Thiele, an Ottawa-based lawyer who works extensively on residential landlord and tenant disputes. Thiele recalls representing a client at the Ontario Rental Housing Tribunal in the early 2000s when an adjudicator said during the hearing that “‘he would be shocked if every rental building in Ottawa didn’t have a pest problem,’ says Thiele. “I think that is the reality all over the province.”

Bandurka generally agrees, conceding that in cities across Canada, one can find apartment buildings where every unit has “something in some way, shape or form.” But he emphasizes that there’s a spectrum of severity and not every building deals with the big three—roaches, rodents, and bed bugs—we fear most. Some may have ants or spiders, which are unpleasant, but relatively easy to exterminate.

“The bylaw is a start,” Bandurka says of Toronto’s plan, adding, as you might expect from someone in his industry, that buildings should have “dedicated pest control programs in place with certified professionals.”

The bylaw, Rent Safe TO, will require every apartment building that’s three or more storeys with 10 or more units be inspected by a bylaw enforcement officer. If the city finds health or safety hazards, including pest problems, they’ll ask the landlord to deal with them. If they find on re-inspection the landlord hasn’t complied, they can levy fines as high as $100,000.

RELATED: How the bed bug took over the world

“It’s not just a slap on the wrist,” says Toronto City Councillor Josh Matlow, who introduced the bylaw. “It’s a big, six-figure number to send a message that if you are going to be willfully negligent, then we’re going to hammer you.”

The trouble is that not everyone with pests has a negligent landlord. Certainly foot-dragging owners and building superintendents exist in abundance across Canada, but others are trying to eliminate pests, to no avail.

From this writer’s own experience with cockroaches, I know it requires a militant discipline to eliminate food sources and administer treatments at the right times in the pest’s life cycle. If you wait too long between treatments, they’re back with a vengeance. It’s a surprisingly involved process, and many landlords simply don’t have the time to stay on top of the problem. Even if they and tenants take extra care, cockroaches can live for a week without water and a month without food—plenty of time to reproduce. Plus, they eat the carcasses of their kin if there’s no other food available, making their annihilation potentially impossible. One tenant I spoke with, who lives in a 1970s era high rise in Toronto’s west end, has had cockroaches for all eight years he’s lived there, despite having pest control treatments every Thursday. I moved out of my own roach-infested apartment after a year of failed treatments, leaving most of my furniture behind so as not to bring the pests with me.

Folks who’ve had bedbugs will tell you those pests are no better. Back in 2014, Ray Noyes, a tenants’ rights advocate based in Ottawa, wound up in the hospital after needing four months of weekly blood transfusions because of an acute bout of anemia. “I could only walk for about two minutes before sitting down and resting for five minutes to catch my breath,” says Noyes. Though the doctors knew Noyes had bed bugs at home, they didn’t piece it together that the pests were draining his blood. It wasn’t until his apartment was treated for the seventh time that Noyes started regaining his energy and connected the dots himself. Noyes can’t count how many times his apartment has been treated since, but says, while the problem is being managed, “to this day, I have the great-great-great-great-grandchildren of those vampires still hanging out in my unit.”

Noyes is a member of the Ottawa branch of Acorn, a non-profit that advocates for, among other things, tenants’ rights, particularly those of people who are low-income. The organization is lobbying for landlord registries in the capital with the same objective of Toronto’s new bylaw: to hold landlords accountable for maintaining safe and clean rental stock, and doing so in a proactive, rather than complaint-based, way.

While Noyes considers Rent Safe TO a step in the right direction, he says there’s potential it won’t fix the problem. “If they’re going to prevent people from renting out units where there’s a pest issue that’s not being dealt with, and then they “deal” with it in some sense, it’s just going to be more of the same,” he says. “It’s going to be bandaid solutions.” Part of the problem is the nature of the worst pests—they’re resilient and they reproduce at alarming rates. The other factor, says Noyes, is the for-profit pest control industry that he doesn’t believe is getting the job done. “To me, in a dream world, pest control would be like the paramedic service,” he says. “It would be a public health service instituted by the municipality or province.”

Toronto’s new bylaw comes into effect on July 1, but it will be years before the City knows whether it reduced the burgeoning pest problem. If it does, other cities may follow, with either bylaws or licensing programs similar to the one to which restaurants are subject. “The status quo is unacceptable,” says Councillor Matlow. “Based on every nightmare story I’ve heard, I’m confident that the city needs stronger tools than to just say ‘pretty please do it.’ But if you have the rules and you don’t have anyone to enforce them,” he adds, “they have no weight.”