John Vaillant’s new big-cat thriller: Book review

Vaillant’s first novel takes its title from the pre-colonial spiritual bond between some of Mexico’s indigenous people and the jaguar.

Share

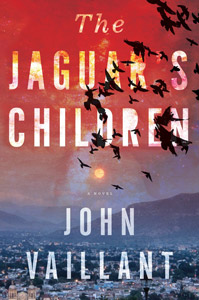

THE JAGUAR’S CHILDREN

John Vaillant

John Vaillant evidently has a thing for big cats. His acclaimed non-fiction book The Tiger—named one of 2010’s best books by Maclean’s—won legions of loyal readers with its true tale of a Siberian tiger first taking revenge and then being hunted. This new book, Vaillant’s first novel, takes its title from the pre-colonial spiritual bond between some of Mexico’s indigenous people and the jaguar. In choosing this central image, Vaillant more than hints at his intention to lead the reader to some deep, old places.

But he draws his material straight out of the news, too. The narrator is Hector, a young Mexican who finds himself trapped in the welded-shut tank of a water truck that’s being used to smuggle would-be migrants over the border into the U.S. The truck breaks down in the desert, and the “coyotes” who were supposed to drive it to El Norte take off, promising to return with help. To fill the terrifying hours and days that follow, Hector records the story we’re reading as sound files on a cellphone, always praying for a strong enough connection to reach the outside world.

The claustrophobic scenario makes Hector’s reflections feel real enough. He’s piecing together how he got into such a fix. He comes from Oaxaca, a poor state in southwestern Mexico, and his family roots are in the small farms where corn, beans and squash grow up against the jungle. Although Hector has been to university and speaks English, he’s closest to his sturdy grandfather. Vaillant paints some genuinely touching scenes between them, but also gives in to the temptation to invest the abuelo with a predictable sort of rural wisdom. Asked by his grandson how a little kernel of corn can grow so big, the old man intones, “It’s the god inside doing this…”

Sometimes Vaillant lets a non-fiction writer’s urge to expound on what he’s learned about Hector’s people overwhelm the story. He gives us doses of the history of Mexicans heading for the U.S., even some statistics. A key plotline delves into the dangers of genetically modified corn mixing with Oaxaca’s native strains. Yet the powerful suspense in Hector’s awful situation, and the compelling mystery of what brought him to the belly of this particular metal beast, are enough to keep this fast-paced novel from feeling merely preachy.