Few Canadians ever set foot on a First Nations reserve, and that’s a problem

An in-depth survey finds the vast majority of non-Indigenous Canadians live sealed away from First Nations people and their communities. Is it any wonder we’re so divided?

A family unloads their boat after a day of relaxing on the Grand River at Chiefswood Park next to the Chiefswood National Historic Site. The park contains 20 acres of lush nature. The Grand River has been given a Heritage River designation by the Canadian Heritage Rivers System that encourages the long-term management to conserve the natural, cultural and recreational values of rivers in Canada. (Photograph by Andrew Lahodynskyj)

Share

With her family back home in London, Ont. and her suitcase of belongings in the northern Ontario reserve of the Kitchenuhmaykoosib Inninuwug First Nation, Monique Castonguay was on a day trip to Bearskin Lake First Nation in 2016 when she was asked to stay.

Her visit was supposed to last a few days as part of a program called Reconciliation Trips, which seeks to connect non-Indigenous Canadians with First Nations peoples. But when Castonguay, an educator in southwestern Ontario, learned that Bearskin Lake’s schoolteacher was days away from a two-week leave for her honeymoon, Castonguay suggested a few strategies the locals could use to keep the children focused on school during their teacher’s absence. Instead, one of their leaders asked: “Why don’t you just stay for two weeks?”

So she did. And on her first morning in class, zero kids showed up.

But over the next fortnight, Castonguay gradually won them over—playing cards; jumping in the lake with them on a rare 30-degree day. By the end of her stay, they were all showing up for class, and Castonguay was headed home with a message of reconciliation—and exposure to the challenges of life on First Nations reserves of which the vast majority of Canadians are simply unaware.

Castonguay’s trip puts her among the minority in Canada, not because she spent a few weeks on a First Nations reserve, but because she spent any time at all.

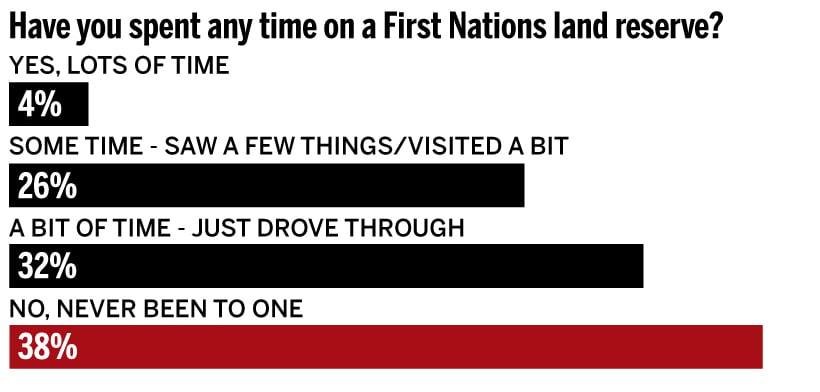

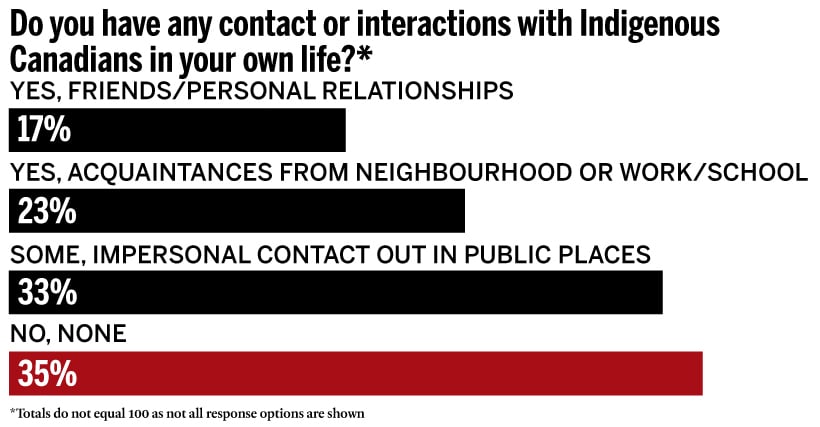

The most in-depth public opinion poll since Trudeau’s Liberals took office in 2015 suggests that, despite the Prime Minister’s reassurances the country is working towards reconciliation, about two-thirds of Canadians have either no contact with Indigenous Canadians or, at most, some impersonal contact in public spaces. Nearly 40 per cent of respondents said they have never been to a First Nations reserve; another 32 per cent said they’d merely driven through without staying to visit or see a few things.

As Maclean’s reported on Thursday, the results of the nationwide survey from the non-profit Angus Reid Institute highlight a divided nation when it comes to both symbolic and existential questions on Indigenous matters. Yet it invites the question whether the lack of exposure most Canadians have might underlie some of those attitudes.

The extensive survey polled more than 2,400 Canadians and purposely oversampled in areas with higher Indigenous populations. It found that, despite that lack of direct contact, the top three descriptors for life on First Nations reserves from both Indigenous and non-Indigenous people are social problems such as substance abuse, a dearth of job opportunities stemming from a poor economy, and a lack of social services like education and health care. It’s a media-filtered perception, and not the sort that inspires casual visits from outsiders keen to learn more.

“Media coverage of Aboriginal people generally focuses on negative outcomes,” says Ken Coates, a senior fellow in Aboriginal and northern Canadian issues at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute. “We have a suicide epidemic and we pay attention to it, as we should. We have excruciating poverty so we pay attention to it, as we should. We have a housing crisis in Nunavut and we talk about it, as we should. But we don’t talk about the substantial increase in Aboriginal employment in the resource sector. We don’t talk about the success of Aboriginal development corporations. We’ve got a one-sided public image of what’s going on, so we get this image that we’re not making much progress, so why are we trying?”

If Canadians were to drive around Six Nations of the Grand River—Canada’s largest First Nations reserve by population, with about 13,000 people—they’d see a Tim Hortons, locals on ride-on lawnmowers trimming the grass, a popular burger restaurant once featured on Food Network Canada, crafts stores and a handful of educational tourist sites. Yet, despite its location within 100 km of Toronto and Hamilton, the town is hardly bustling with tourists. Not counting organized school groups bused in for field trips, Six Nations’ Woodland Cultural Centre received approximately 1,500 visitors during last year’s summer tourist season.

That’s about 10 people a day. Fewer than half came from Canada. “I’ve had [non-Indigenous] tour guides ask, ‘Can we come here without you?’ Yeah, we’re just a community. You can come stop in,” says Alysha Longboat, a cultural coordinator at Six Nations. “I think there are stereotypes and lingering myths.”

Six Nations hasn’t gotten glowing media coverage in recent years, in large part due to a clash between them and the nearby town of Caledonia, where Six Nations locals blocked off a main road into the town to protest a proposed housing development along the boundary of the reserve—land for which Six Nations had claim under the 1784 Haldimand Proclamation. “My father did land claims for this community, so he was constantly going to the courts, as per the western legal route of how to settle these things, and it didn’t go anywhere,” says Janis Monture, director of tourism and cultural initiatives at Six Nations. “Before that, we had a chief who went to the United Nations in New York on our behalf to talk about our land and our rights.” Nothing was resolved; ergo the protests.

It’s a history distinct from other First Nations communities’, and one too complex to understand in a single visit. “This history of protest is generation upon generation of people trying to get our rights,” Monture says. And while other Indigenous communities might look up to Six Nations from an economic standpoint, it has its problems: as in so many First Nations, parts of the community remain under boil-water advisories.

“Most of the people in Canada who are non-Indigenous have immigrated from somewhere else, so the understanding is if things are hard, you can go somewhere else,” says Sheryl Lightfoot, Canada Research Chair in global Indigenous rights and politics at the University of British Columbia. “That’s a different base assumption than for Indigenous people, who have been living here since time immemorial. That’s not their history.”

And it’s a history most Canadians have yet to learn. Only eight per cent of Canadians said they have “a good understanding” of Indigenous issues, according to the survey, compared to 17 per cent who said they “don’t know much at all about these issues.” Nearly half the country said they know “a bit—the basics.”

Lightfoot warns that giving non-Indigenous Canadians some limited exposure to life on reserves will not, on its own, change hearts and minds. “If you’re starting from the assumption that Indigenous people just need to integrate, then you go see their living conditions, that just reinforces the starting assumption,” she says.

That could explain why, in one of the survey’s most surprising findings, Canadians with more exposure to life on reserves were those most likely to take a hardline stance on Indigenous issues—such as saying the country spends too much time apologizing for residential schools and that Indigenous Canadians would be better off if they integrated more into broader Canadian society.

These hardliners are disproportionately located in Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta, where the greatest proportion of respondents—nearly nine out of 10—said they they do have interactions with Indigenous people, and where respondents were much more likely to say they’d been to First Nations reserve compared to other the rest of the country.

“We have to get to the idea that there can be two nations living side by side. There can be ways of rethinking this so people can maintain their own nationhood, and ways of being, within our system,” Lightfoot says.

Last year, after Grand Chief Sheila North of the Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak called Manitoba Premier Brian Pallister’s government the “most racist provincial government in Canada,” she invited the premier to visit an Indigenous community—for a few days or a week or a month—to see what it’s like to live there. “He didn’t take up my offer,” North says. “We need to promote and provide exchange opportunities so people understand each other’s culture.”

Former Northwest Territories premier Stephen Kakfwi recalls meeting a politician about a decade ago who said he had never been outside the city boundaries of Yellowknife. “Never been to an Indigenous community—and yet he was elected to represent over 30 other communities in the Northwest Territories and pass legislation,” Kakfwi says, adding that ignorance is “not only a southern problem. Sometimes we have it up here too.”

READ MORE: Want common ground on First Nations issues? Start by fixing the water supply

Certainly some in the south have made heartfelt gestures by visiting First Nations communities. Two years ago, as part of a the same Reconciliation Trips program as Castonguay’s, a group of Torontonians including the mayor, John Tory, visited the Kitchenuhmaykoosib Inninuwug and Bearskin Lake First Nations communities over a four-day span. The locals welcomed the visitors to sleep in their homes.

“Some of those people didn’t have proper running water, toilets and other facilities,” says Gary Kaminawatamin, a band councillor on the Bearskin Lake First Nation. “They don’t have much, but it shows they’re generous.” Tory later wrote about the lessons he learned on his visit, including the lasting impact of residential schools. The trip made him a better leader and a more informed citizen, he said.

This year, the Reconciliation Trips were indefinitely suspended due to a recent spate of suicides in the region.

Castonguay hasn’t been back to Bearskin Lake since her two-week teaching tenure. She has, however, remained in regular contact with many in the region, while organizing fundraising drives to deliver them goods—flour, coats, hockey sticks toys, coffee—at Christmas.

But she is also making strides as Indigenous education lead for her school board, including arranging for students from her daughter’s school to visit the Woodland Cultural Centre in Brantford, Ont. to learn about the Southwestern Ontario’s First Nations history.

“She was 13 at the time, and when my husband picked her up [after the visit] they were on their way to a hockey game in Goderich,” Castonguay says. “In two hours, she taught my husband more about residential schools than he had learned in his entire schooling.”

With files from Kyle Edwards