Cannabis is legal. Now about those pardons for pot possession?

There is still no timeline for Canada’s plan to pardon people for simple pot possession. And even when it happens it won’t wipe records clean.

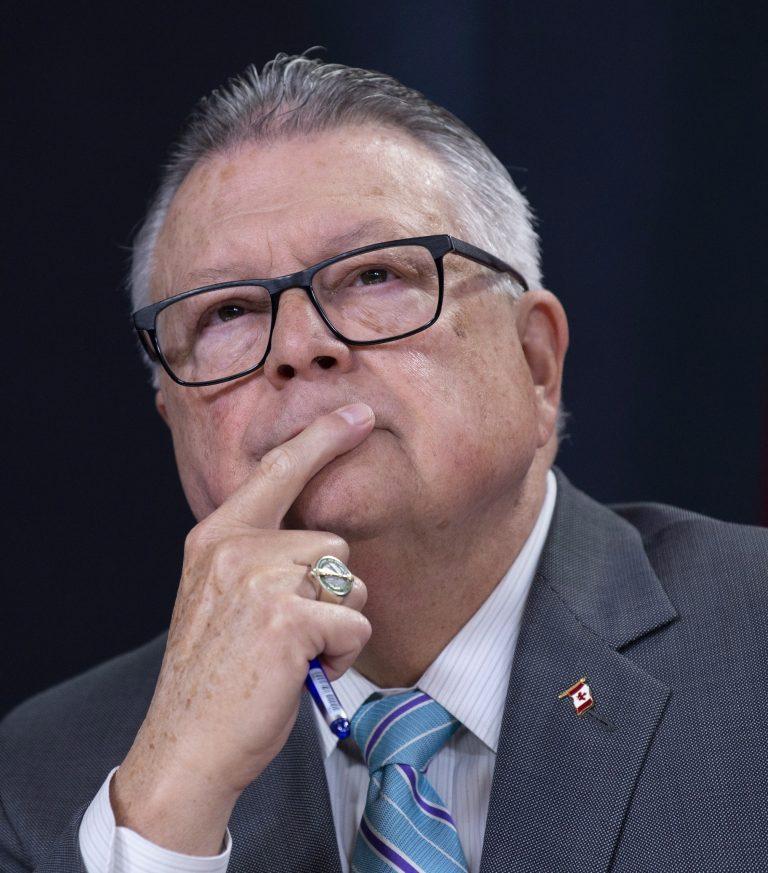

Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness Minister Ralph Goodale listens to a speaker during a news conference on the Cannabis Act in Ottawa, Oct. 17, 2018. (Adrian Wyld/CP

Share

There has been something profoundly bewildering—surreal even—about the “Wait. Wait. Wait…okay, now it’s fine” nature of Canada’s shift to legalized marijuana. It was more than three years after Justin Trudeau—then leader of the Liberal Party campaigning to become prime minister—committed to doing so that his government passed C-45, the Cannabis Act, legalizing the drug in Canada as of today.

Literally overnight, pot went from being a verboten substance to being widely available from slick, fully licensed private retail outlets and government-run websites promising delivery by Canada Post carriers.

But an estimated 500,000 Canadians already have a criminal record for possessing this now-perfectly legal substance. And now, the message from the government on dealing with that issue is once again, “We’re getting to it.”

“As we go about changing a legal regime that has existed for nearly a century, there are many steps that must be taken in proper sequence. It is not a singular event, like flipping a switch,” Public Safety Minister Ralph Goodale said in a press conference on Wednesday morning. “It is a process. Part of that process will involve at least one more piece of legislation.”

That legislation, Goodale said, would enable Canadians with a record for simple pot possession to apply for a pardon with no waiting period or fee, both of which are currently required. But there is no timeline for enacting that legislation or even tabling it in the House of Commons; Goodale said only that he expects the bill to be presented before the end of this year.

“What we said was as soon as the law changed that we would be in a position to move forward on this important part of the equation, and that’s what we’re doing as of today,” he said, when asked why the government didn’t already have something ready to go. “The law changed at midnight last night, and we are announcing this morning the first steps toward implementing the appropriate pardon process for those with previous charges of simple possession.”

READ MORE: How will marijuana legalization change the U.S. border for Canadians?

It was less of an announcement, really, than a save-the-date card for future action.

Once legalization became a fait accompli, a network of criminal defence attorneys, marijuana advocates and opposition politicians took up the cause of convincing the government to implement comprehensive amnesty on past pot possession charges.

With no timeline and most details of the pardon regime yet to be laid out, the core argument of those advocates remains unchanged, and it is this. Lots of Canadians smoke weed and have done so for years; at least half a million of them have been caught and acquired a criminal record for their personal use of a substance the government has now decreed perfectly safe and legal. Last year alone, although the numbers have been steadily declining, 13,800 Canadians were charged.

What’s more, statistics suggest marijuana use doesn’t vary much across racial groups, but these charges have been laid in wildly unequal ways that target people of colour and vulnerable communities much more than other Canadians.

A Vice News investigation earlier this year, for example, found that Indigenous people in Regina were almost nine times more likely to be arrested for pot possession than whites, and blacks in Halifax were five times more likely. A 2017 Toronto Star analysis found that black people in that city were three times more likely to be arrested for marijuana possession than their white counterparts.

“Police aren’t running around Forest Hill in Toronto, the richest neighbourhood, trying to see if anyone is smoking marijuana in the basement. And let me tell you, many of them are,” Annamaria Enenajor, a lawyer with the Toronto firm Ruby, Shiller & Enenajor, and director of the Campaign for Cannabis Amnesty, said a few weeks before legalization. “What that tells me is this is not simply about cannabis, this is about equality. It’s about the promise of being equal before the law, and the fact that there are certain Canadians who cannot rely on that promise.”

And Enenajor and others working on this argue that the consequences of having a record for doing something so common are real and long-lasting. Job applications, background checks for volunteer positions, applications to rent an apartment or customs questions when travelling abroad can all be torpedoed by the admission or discovery of a record for pot possession.

“It’s really low-hanging fruit, in the sense that there’s no principled opposition to this,” says Enenajor. “It doesn’t make sense for anybody to continue having these records, and it has such an impact on people’s lives.”

Prior to the announcement Wednesday, NDP justice critic Murray Rankin had tried to goad the government into action by introducing C-415, a private member’s bill aimed at mitigating the fallout of a now-extinct crime. He lives in Victoria, “where you really have to work to get charged,” and was shocked to discover how much it was happening elsewhere. “If middle-class white kids in downtown Victoria were being harassed, I know I’d hear a lot about it,” he says. “But if it’s Indigenous kids hanging around Regina or blacks in Toronto or Halifax, they’re the ones that are disproportionately affected, and I don’t think we hear as much about it because they don’t have the political clout that some of the others that are less affected would have.”

Rankin modelled his bill on C-66, a bill passed in June which automatically expunged and destroyed the records for a range of historical offences revolving around same-sex relationships. An expungement means the offence is deemed never to have occurred; the difference between that and a pardon is roughly analogous to the distinction between an annulment and a divorce. “That means you could truthfully say on that form, to the landlord or to the employer, ‘No, I don’t have a criminal record,'” Rankin says. “It makes all the difference. It’s not like I was pardoned for it; it never happened.”

Goodale said Wednesday that the government will offer pardons and not expungements because of the nature of the offence. “The laws with respect to cannabis that have existed historically, we believe are out of step with current mores and views in Canada,” he said. “We are drawing the distinction with expungement, which is reserved for cases of profound historical injustice where a Charter rights violation was involved.”

The government also believes pardons can be enacted more quickly and cheaply than expungements.

However, John Conroy, a criminal attorney in Abbotsford B.C. who spent years at the forefront of the battle to legalize medical marijuana, believes any solution must comprehensively erase people’s records, or it will be useless. Conroy likens a pardon to the government simply tracking down your file and moving it to a different filing cabinet—the detritus left behind can still cause trouble for people, especially given the interconnected nature of digital record-keeping. “What has become the biggest problem is not the criminal record so much—although it will be important to eliminate them somehow—but anything in a digital database,” he says.

Conroy recently had a client who ran into problems obtaining a security clearance because his record check turned up four absurdly vague weed-adjacent interactions with police, such as simply being seen near a car that someone complained smelled of marijuana, even though no charges were laid.

To really solve this problem, he argues the government will have to broaden its approach to eliminate everything related to pot possession, including stays of proceedings, withdrawal of charges and so on, and it will have to nuke the records entirely—not simply shuffle them into a different category. “These people have been involved in conduct that is of no harm whatsoever to anyone in society,” he says. “And they are prejudiced in their future in all kinds of ways.”

Criminal defence attorneys and advocates in the field say that weed has often been used as a reason for police to get involved with certain people they happen upon in public, and plenty of statistics demonstrate that bias plays a role in those decisions and racialized people are disproportionately targeted. Leo Russomanno, a criminal defence attorney and co-director of the Ottawa chapter of the Criminal Lawyers’ Association, describes the “classic example” like this: a police officer would smell marijuana and have grounds to arrest someone, at which point they’re entitled to a full search of the person and vehicle. That could yield evidence of other offences, or they could run the person’s name through a database and discover they’re on bail or out past curfew.

“One of the reasons why we continue to see enforcement of the law is because marijuana is—and pardon the pun or whatever you want to call it—but it’s a gateway offence,” he said a few weeks before legalization. “Like many drugs, but I think with marijuana in particular, it does serve that function of opening the door to many police powers.”

In California, a provision for people to apply to have their records wiped clean was wrapped into the state’s marijuana law after citizens voted in 2016 to legalize pot; this fall, it passed a new bill that puts the onus on the state to identify people and clear their records. The city of Oakland went even further, reserving half of its cannabis permits for people with low income or living in high-crime neighbourhoods, or who had been convicted of a pot-related offence, in a bid to help those most affected by enforcement benefit from legalization.

The cities of San Diego, San Francisco and Seattle (marijuana has been legal in Washington State since 2012) also recently announced that they would clear previous pot convictions from people’s records.

Being locked out of a market that’s now proving lucrative for plenty of others—including former cops and politicians—is one of the things that most bothers Jeff (who only wished to be identified by his middle name) about the pot charges on his record.

The Ottawa resident is now in his late 30s, and when he was 18, he was on a road trip out west with a couple of friends when police found some weed that belonged to Jeff in the car. That same year, he was busted for possession for the purpose of trafficking, and for trafficking again a decade later. A lawyer eventually got the simple possession charge tossed, but Jeff was convicted of trafficking and spent a few years under house arrest.

“The thing that bothers me is I can’t work in the cannabis industry. I used to be a grower, and I can’t pass the security clearances to even work at an LP,” he says, referring to a licensed producer.

His broader employment prospects are severely limited by his record, too; it’s easy to get a construction job, he says, but employment with an oil patch company, for example, is a no-go because he can’t pass the security clearance. “It annoys me that people are profiting from it and I’m still sitting here with a record,” he says. “I feel like I’m just being punished forever.”

One of those licensed producers, Aurora Cannabis, recently gave a pragmatic boost to advocacy efforts, in the form of a $50,000 donation to Enenajor’s Campaign for Cannabis Amnesty. Cam Battley, Aurora’s chief corporate officer, is full of praise for the “courageous and correct” decision the federal government made to legalize pot, but now says it’s crucial to keep the pressure on them to tackle the rest of it. “Now we have the opportunity to lead on the next step, which is to look back,” he says. “Not just look forward—that’s great—but look back and see what we’ve done in the past and fix it.”

For Enenajor, the government’s wait-and-see response would be more reassuring if they hadn’t spent the last three years failing to deal with other low-hanging judicial fruit like their pledge to get rid of mandatory minimum sentences.

When the government moved ahead with marijuana legalization, the first question she heard from clients with records for pot possession was, “What’s this going to do for me?” Enenajor did not have encouraging news for them, and she’s troubled by the stark differences in how various players from the old regime have fared under the new one. “I have to tell them, ‘Actually, remember the guy who was the Toronto police chief a couple of years ago, Julian Fantino, who was so against cannabis, he likened it to murder? Well, guess what, he now is going to run a multi-million-dollar cannabis company he’s invested in,'” she says. “And sorry, but there’s no benefit to you.”

Now, clients like hers may have some relief coming their way. But it’s anyone’s guess how long that will take or how effective it will be when it lands.