The number of soldiers citing medical reasons for leaving the military is soaring

Politics around veterans can get bitter fast, and beneath that tension lies a huge increase in disability claims

Canadian Forces members drive a LAV onto Parliament Hill during the National Day of Honour in Ottawa on Friday, May 9, 2014. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Sean Kilpatrick

Share

During his national town-hall tour in the first few weeks of 2018, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau fielded more than a few dicey questions. Easily the biggest political risk Trudeau took, though, had to be his exchange with an irate veteran in Edmonton. Brock Blaszczyk, 27, who lost his left leg to an improvised explosive device in Afghanistan in 2010, was wearing his medals and not hiding his frustration. He demanded to know why the federal government was fighting some veterans in court over disability pensions. “Because,” Trudeau said, “they are asking for more than we are able to give right now.”

That candid answer prompted howls of outrage from veterans’ advocates and opposition politicians. But, in a recent interview, Blaszczyk expressed mixed feelings on whether or not Trudeau was out of line. “I don’t know,” he said. “It’s the first time we actually had a straight answer from the government, to tell you the truth. At the end of the day, it’s about money.” Indeed, it’s about a lot of money, as some fine print on military disability costs buried in last month’s federal budget made even clearer, and additional data and details provided to Maclean’s help explain more fully.

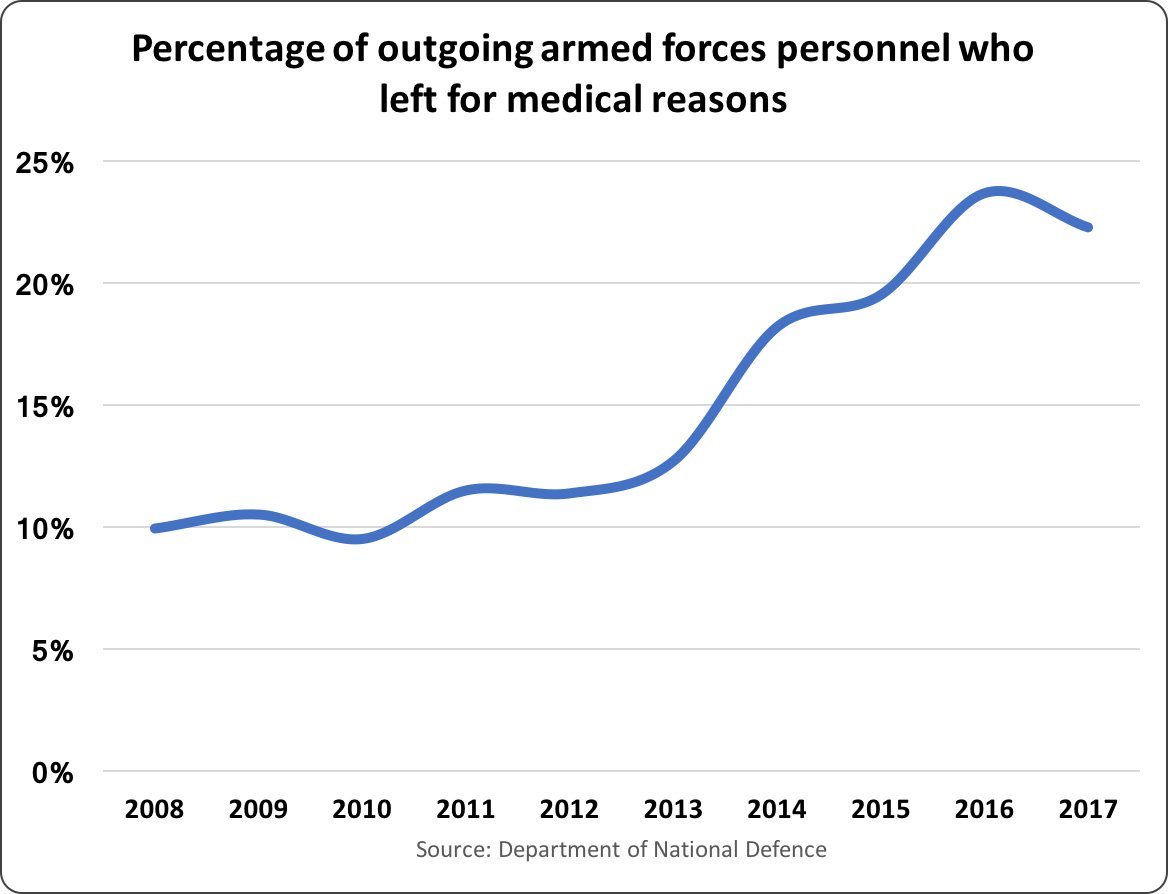

Near the back of Budget 2018, and without much explanation, the government plunked down $623 million in 2017-18 to replenish what’s called the Service Income Security Insurance Plan, an insurance fund for Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) members, plus another $177 million for 2018-19 to keep the plan financially sustainable. The reason for the combined $800-million cash injection: the soaring number of troops exiting the CAF under what’s called “medical release,” rather than just voluntarily leaving, which means many more of them are making disability claims.

The key figures from the Department of National Defence (DND) show that a decade ago, in 2008, fewer than one in 10 members leaving military did so through medical release. By last year, the number doing so had risen to more than one in five, or 2,214 of the 9,941 members who left the military in 2017. If you consider only regular forces, and leave out reservists, more than one in three who left the CAF last year officially did so for medical reasons, or 1,869 out of 5,163.

That means far more disability claims overall, and within that total, the number of stress-related mental health cases has soared. About 40 per cent of medical releases last year were for mental health, DND estimates, and about half of those included a post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) diagnosis. Nobody disputes that these claims are often far trickier to assess than physical injuries.

That means far more disability claims overall, and within that total, the number of stress-related mental health cases has soared. About 40 per cent of medical releases last year were for mental health, DND estimates, and about half of those included a post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) diagnosis. Nobody disputes that these claims are often far trickier to assess than physical injuries.

“When you have a specific back injury, there’s a pretty formulaic medical approach to it,” says Sayward Montague, advocacy director with the National Association of Federal Retirees, which counts about 60,000 veterans among its 180,000 members. “With mental health, and PTSD specifically, there are so many variables that are hard to control.”

Veterans who qualify for disability benefits receive up to 75 per cent of the salary they were earning when they left the Forces. They are guaranteed benefits for 24 months initially, or until age 65 for those completely disabled. That doesn’t come close, though, to telling the whole complicated story. A lot of the current controversy stems from an unpopular 2006 reform that moved to lump-sum payments, rather than ongoing pensions, for wounded ex-soldiers.

READ: Service dogs help veterans with PTSD. Why won’t Ottawa?

In his 2015 election campaign, Trudeau responded to their discontent by promising to bring in a choice between the two options. Late last year, his government unveiled a $3.6-billion package designed to fulfill that pledge, and, at the same time, streamline a range of other Veterans Affairs programs. Critics complained, however, that the pension on offer is still less generous than the pre-2006 plan.

Six disabled Afghanistan vets lost a B.C. Court of Appeal case over Ottawa’s pension obligation to them—the dispute Trudeau alluded to in Edmonton. Their group, called the Equitas Society, has asked the Supreme Court of Canada to hear an appeal of that ruling. Whatever the top court decides, bitterness over the legal clash is bound to remain a sore point. And the possibility of Ottawa facing off again against ex-CAF members in court exacerbates tensions over how Veterans Affairs treats ex-soldiers seeking benefits.

That fraught relationship came up a lot in a series of town-hall style meetings with veterans held last fall by the federal retirees association. “Some interactions with Veterans Affairs staff were extremely positive,” Montague said. “There were other cases where veterans and families felt disrespected.”

Blaszczyk sees it much the same way. “They have great systems in place right now,” he said. “The problem is that Veterans Affairs acts more like an insurance group than like an advocacy support group for veterans.” But Veterans Affairs Minister Seamus O’Regan says his department has recently turned a corner, declaring early this month that there’s been a “shift in focus away from our own internal processes, in favour of the veteran.”

Still, the sheer volume of disability cases will keep the system under stress. The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBCS), which oversees administration of federal employees, gave Maclean’s a written summary of the three main factors it says are pushing up military disability claims: the average age of men and women in uniform has climbed; CAF members are more aware of mental illness than in the past; and “a greater awareness of benefits has prompted a larger number of people to seek medical release.”

The rise of mental health claims is often chalked up to Canada’s difficult 2002-11 combat mission in Afghanistan. But TBCS says dangerous deployments— like Blaszcyk’s tough tour in Kandahar—are far from the only source of mental health risks. Even at home in Canada, military service means moving often and spending time on duty far from family. “CAF members may be exposed to numerous stressful events and be at risk of experiencing job stress at home as well,” TBCS said.

And then there’s that “greater awareness of benefits” factor. Listing programs from indexed annuities and vocational rehabilitation, to priority hiring into federal jobs and disability pensions, TBCS said the fact that military personnel know more about all these potential benefits has “increased the number of people who are identifying their medical issues, and releasing medically rather than voluntarily or at the compulsory retirement age.”

It’s ironic that navigating the proliferation of benefits meant to help veterans seems to have emerged as a prime source of their frustration. “The supports and information have been inconsistent,” Montague said. “It’s kind of confusing for people who are leaving that closed ecosystem of the military, and going out into the civilian world, where you’re looking for your own family doctor, for example, when nobody can find one.”

Even with billions of new dollars on the table, Blaczcyk said the Liberals must end the feeling among former CAF members that when they seek benefits, a battle with bureaucracy awaits them. “I get that the government is trying to do something better,” he said. “But when you have them denying people—saying, “no, no, no’—what good is it?”