What the turmoil in oil markets means for Canada’s economy

Negative oil prices are a warning sign that the economic fallout from COVID-19 could be even worse than a lot of people are expecting

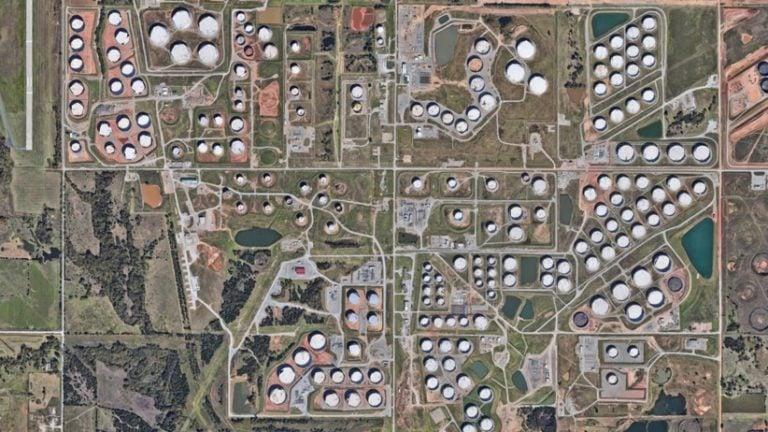

Oil storage tanks near Cushing, Oklahoma (Google Earth)

Share

You don’t have to be a commodities trader to know that something extremely unusual is happening to oil prices. For the first time ever, the price of West Texas Intermediate crude dropped below zero on Monday, ending the day at negative $37. The decline seemed to have come out of nowhere, too, with prices plummeting by 302 per cent over the course of a few hours. (Prices “rebounded” on Tuesday to $9 at the time of writing.)

With Canada still very much an oil economy, it’s likely that a lot of Canadians took notice of this unprecedented price decline, but what does it really mean and what might be the impact on this country’s already struggling finances?

Too much oil supply, not enough demand

There are a couple parts to this price plummeting story, but we’ll start with supply and demand. In some ways, commodity pricing is easy to understand. The more of something people want to buy, the higher the price goes. If that item is overproduced and therefore readily available anywhere and from anyone, sellers will make the price more attractive so that buyers will take it off their hands. Ideally, supply and demand would be in balance—companies would produce about as much oil as people want to buy—but that’s not what tends to happen.

Over the last several years, oil production has ramped up significantly, particularly in the U.S. America is now producing 140 per cent more barrels of oil per day than they were in January 2010. With energy economies like Canada, Saudi Arabia and Russia still pumping out the Texas tea, you’ve got a lot more oil now than you did a decade ago.

READ: A different type of crisis demands a different type of data

While supply and demand has, more or less, been in balance for a few years—partly because Russia, Saudi Arabia and other Middle East nations have cut production to keep oil prices stable—there have been times when supply has outpaced demand, which has then caused prices to fall.

Since mid-March, when people started staying indoors, demand for oil has fallen off a cliff. People don’t need gas anymore, which is the main end-product of oil, as they’re not driving or flying anywhere. At the same time, production continues, with U.S. oil and gas producers still pumping out about 12 million barrels of oil per day.

Nowhere to store excess oil

What happens to U.S. oil that doesn’t get purchased? It gets stored in large crude oil tanks, mainly in Cushing, Oklahoma, but also in other areas across the country. Oil companies can store up to 76 million barrels of oil in Cushing, but those storage facilities are nearing capacity. Amrita Sen, chief oil analyst at Energy Aspects, told the Financial Times that Cushing’s storage tanks will be entirely full at some point in May.

Therein lies the problem: There’s too much supply, too little demand and nowhere to store all the stuff that’s still getting produced. If you can’t convince someone to pay you for something you’re selling, and if they won’t even take it off your hands for free, then you might consider paying someone to take possession of an item you want to get rid of. (There’s more to it than that—prices fell when they did in part because of how oil trading works, but it’s complicated.)

What does the oil price crash mean for the economy?

Not surprisingly, negative or ultra-low oil prices aren’t good for oil companies or oil-producing countries like Canada, says Martin Pelletier, a Calgary-based portfolio manager with Wellington-Altus Private Counsel Inc. If no one’s buying what you’re selling then you’ll have no choice but to go out of business. It’s no different than the restaurant down the street having to permanently close up shop during COVID-19 because of a lack of customers.

According to Natural Resources Canada, the oil and gas sector accounts for 5.6 per cent of the country’s gross domestic product and between 11 per cent and 20 per cent of total exports, depending on the year. If more companies close and more layoffs happen, then it’s pretty clear that Canada’s economy will be even more compromised. “The impact will be even more profound in Canada and it will work its way into other areas,” says Pelletier.

The rapid price decline is also a sign that the economic devastation from COVID-19 may be worse than many people, including stock market investors, think. (The S&P/TSX Composite Index was down three per cent on Tuesday, which is a lot in normal times, but not so much today.) “The energy market is telling you that broader economies are in awful shape,” says Pelletier. “It’s going to be terrible. The average person is underestimating COVID’s economic impact.”

What about gas prices?

The only silver lining for cash-conscious Canadians is that gas prices will fall even further, though this only really matters if you’re still commuting to work. Unfortunately, you won’t get paid to fill up your car, but prices could fall by another 10 cents a litre if oil stays low for a while, says Patrick De Haan, head of Petroleum Analysis at Gas Buddy. As well, you’ll still have to pay taxes on gas, which in Ontario adds 37 cents on every litre pumped.

The other thing to keep in mind is that oil prices won’t be down forever. When you look at the futures market and what traders are willing to pay in the summer and fall for a barrel of oil, it’s back into the $20 range. That could drop if demand doesn’t pick up, but there is at least some hope that when the social distancing restrictions end people will start driving again.

Even so, prices may not rise enough to help Canada’s energy sector—Pelletier says the right price level for oil is around $45 a barrel—but negative oil won’t become the norm.