Canada’s audacious plan to beat an unbeatable enemy on this day in 1918

It took the combined efforts of infantry, artillery, armour and air power to overcome the formidable obstacle that was Canal du Nord

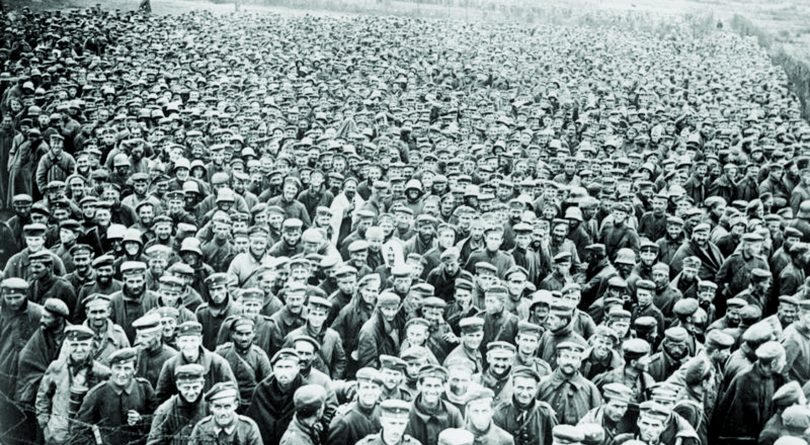

Battle of the Canal du Nord, 1918. (Chronicle/Alamy)

Share

The First World War concluded on Nov. 11, 1918. In commemoration of its 100th anniversary, Maclean’s asked renowned historian J.L. Granatstein to tell the story of Canada’s renowned final push to the end of the war, known as the Hundred Days. Read those dispatches here.

After the Canadians broke the Drocourt-Quéant Line, the Germans retreated eastward, taking up prepared positions on the far side of the uncompleted Canal du Nord. They had to keep the city of Cambrai, the road and rail junction, and the key supply centre for their armies in northern France. The canal had been under construction before the war, the northern section passing through marshy ground and, flooded by the enemy, almost impassable. To the south was a 2.3-km dry portion, and it was here that the Canadian Corps would attack.

The canal itself posed a formidable obstacle. The bed was wide, the walls high. The eastern bank was lower but still an obstacle; so, too, were the defences the Germans had in place. Their trench system and wire entanglements were strong, their machine guns numerous. At Bourlon Wood, the height of land dominating the area, the enemy had massed guns and men. In all, seven divisions protected the way to Cambrai.

RELATED: The forgotten Chinese labourers of the First World War

Lt.-Gen. Sir Arthur Currie had some time to make his plans, his troops resting and integrating reinforcements after the heavy casualties at Amiens and the D-Q Line. His intentions were audacious. He decided to funnel two divisions, or some 40,000 men, through the dry canal bed and then have them fan out onto a 13-km frontage, all the while under fire. The Germans knew an attack was coming, the only surprise possible being the exact moment the assault would commence. The difficulty for Currie was that by concentrating the assaulting divisions in a small area, he risked the real possibility of heavy German bombardment with shrapnel and poison gas, which could cause terrible casualties and destroy the chance of success. His British superiors advised against his plan, but Currie insisted that his Corps could do it.

Currie did have many tools at hand. His artillery support was huge and, while there would be no preliminary bombardment, the barrage supporting the crossing would be devastating. The Canadians had also perfected the art of locating the enemy guns with aerial spotting and sound detection, finding 113 guns before the operation, and the artillery was poised to eliminate them. The Canadian engineers, easily the best in the British Expeditionary Force, were also ready to throw 17 bridges across the canal as soon as the infantry had crossed. That would allow the guns, tanks, supplies and reinforcements to support the leading waves.

The attack went in at 5:20 a.m. on Sept. 27 behind the barrage. The defences on the edge of the canal collapsed quickly, but Bourlon Wood was a tougher nut, and casualties in the three attacking battalions were heavy. The Wood was nonetheless in Canadian hands by dusk, and by nightfall the attackers had broken the main enemy trench system. Currie wrote that the fighting “was quite severe,” but he had to chuckle when he learned that a count commanding a German cavalry brigade had been taken prisoner, complaining bitterly that his captors had taken “his buttons, his shoulder straps, his Iron Cross, his ring, his money, and made him carry a stretcher about six kilometres.” All the Canucks cheerfully looted prisoners for souvenirs even in the midst of battle.

READ MORE: The lifespan of a Canadian First World War pilot was ten weeks

Above the battlefield, the Royal Air Force had its fighters strafing enemy anti-tank gun positions and trying to shoot up reinforcements moving forward. “Countless instances,” Capt. W.H. Hubbard, a pilot from Toronto, wrote, “could be recounted of German gunners being chased away from their guns and then prevented from working them until captured by the tanks.” This was combined warfare, the use of infantry, artillery, armour and the air force working together.

The German resistance continued to be strong, the enemy fighting desperately to hang on to Cambrai. In the six weeks of fighting since the Amiens battle, however, the Corps had absorbed 31,000 casualties, and the supply of reinforcements was running out. Some Canadians had begun to grumble: “In heaven’s name, surely we handful of men (and so few officers),” one soldier wrote of his battalion, “are not to be put thro’ the mill without more reinforcements. We need 400-500 men at once.” The butcher’s bill was high, and soldiers blamed Currie for continuing to send them into combat.

Still, Currie followed his orders, and all four of his divisions attacked on Oct. 1. The 32-year-old Brig.-Gen. J.A. Clark later wrote that “It seemed impossible to break the morale and fighting spirit of the German troops. We felt that this Boche could not be beaten . . . ” Even so, Cambrai was ready to fall.

J.L. Granatstein is a former Director and CEO of the Canadian War Museum and author of many books, including Canada’s Army: Waging War and Keeping the Peace.