‘Don’t you see yourself in us?’: What it means to be Gen Z

Jenniffer Meng: When other generations see students expressing discontent with budget cuts to education or raising awareness about rising temperatures, I wonder, do they not see what we are fighting for?

Jenniffer Meng (Photograph by May Truong)

Share

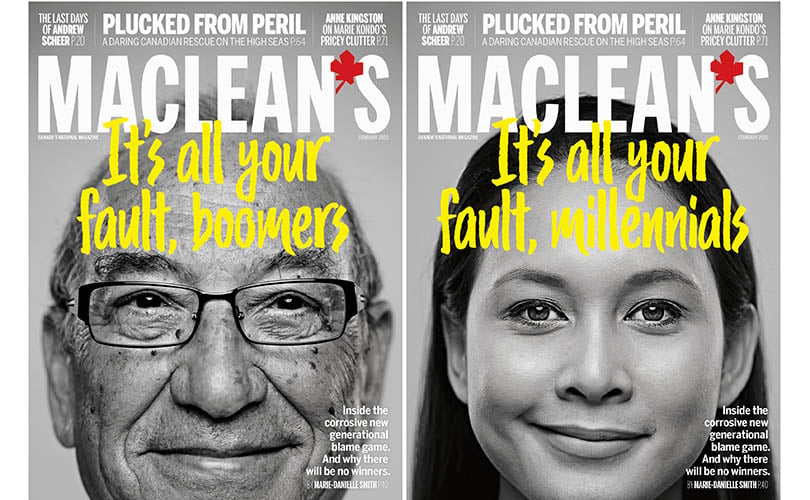

This essay is from the February 2020 issue of Maclean’s magazine, which charts the current conflict between boomers and millennials—one of the defining struggles of our age. The issue has two different covers. Here’s why.

When you think of Gen Z, perhaps the image that comes to mind is a tween hovering over a computer, online shopping, scrolling, posting and commenting. It’s difficult to look at Gen Z and not confine us to these stereotypes. We are the first generation to not know a world without the internet. I remember my first introduction to it—I was around six, I played Barbie.com games to pass the time and watched pirated episodes of Sailor Moon (thanks sis). Today, I’m on my laptop 24/7, and I cannot remember a life without screens or technology.

To older generations, we are slaves to this blue light. When our elders see us on our phones, they accuse us of being obsessed with our Snapchat stories and K-pop idols, of being pornography addicts and gaming junkies. They say we’ve destroyed the nature of relationships and traditions outside of the internet. I can’t say this is entirely false. In reality, some of us do lurk in forums occupied by Neo-Nazis or flat-earthers, and some of us do place inherent value on the number of followers we have or the likes we get on Instagram.

COVER STORY: Inside the corrosive new generational blame game

But this stereotypical image of Gen Z is incompatible with the majority of us. In many ways, technology has become a mascot for Gen Z. In truth, we use technology as a source to keep us informed and to connect with the rest of the world.

The internet has provided us channels to express our creative identities; platforms like Medium allow us to publish our work without the need for an editor or the months-long acceptance or rejection process associated with conventional media. There’s a global audience on Medium, and if your piece goes viral, it could be a career tipping point. We’ve also used the internet to advance our causes: when students held strikes against climate change, they Instagrammed it, tweeted it and made sure to use the respective hashtags. The climate strikes trended on social media and quickly became headlines in newspapers. Soon, our mandate became impossible to ignore.

For older generations who must feel left behind in the golden age of tech advancement, the motives that drive tech use are often unseen. Only clichéd ideas of technology-obsessed teens are perpetuated, and the assumption that technology is being frivolously used becomes all-pervasive.

ANNE KINGSTON: Why intergenerational warfare is a mug’s game

When you focus on such stereotypes, it’s easy to presume that we are not engaged in significant struggles or sacrifices of our own. But the similarities between generations extend far beyond issues of technology, and it may be more meaningful to consider the ways that the generations are similar.

I am 17 and the second child of a family of Chinese immigrants. I come from parents who’ve travelled from Asia to Europe to North America. They hopped from apartment building to concrete basement to bungalow in search of a better life–one where their children could be educated, healthy and happy. I am fortunate not to be facing political or financial instability. From this context, it appears as though any challenge I may experience is incomparable to my parents’ and is temporary. I’ve come to learn that this is far from the case.

When I am not out solving issues with friends and family, I am expected to be academically accomplished. And when I am done being a perfect student and daughter, I am expected to fight. I am expected to fight for rights and freedoms—a future for us and generations that will follow. And when such possibilities are unattainable, I am expected to accept that we’ve done all we could. It is here where feelings of betrayal begin to form, and where generations begin to blame each other.

MORE ESSAYS:

‘We had good intentions but we fell short’: What it means to be a baby boomer

‘Self-sufficient and unassuming’: What it means to be Gen X

‘Directionless and lost’: What it means to be a millennial

When Greta Thunberg is lecturing the world on the dangers of climate change, it’s often the members of the older generations who accuse her of being unintelligent and uninformed. When students gather in Washington D.C. to protest gun laws, the same members call them puppets of the liberal state. They say we have no concept of reality or hard work. They think our lack of experience is tied to our competency. But these comments should feel familiar to older generations—they were told the same things during the Civil Rights Movement, protests against the Vietnam War, the AIDS pandemic, and the list goes on.

I am sometimes confused about why other generations do not see themselves in us. When they see students expressing discontent with budget cuts to education or raising awareness about rising temperatures, I wonder, do they not see what we are fighting for?

At the same time, I am confused about why Gen Z considers older generations to be so alien. We should not forget that boomers were also champions of freedom and social, racial, sexual, economic and political change. Gen Xers, who are now our parents, are products of large-scale social changes due to the rise of MTV and crippling student debt. Millennials are our siblings, who also adapted to the internet early in its inception—they face the same fear of the unknown we do.

But it is a different kind of fear that overwhelms me—the fear that when we are older, we will become these same people we accuse of passivity. We will vote conservative. We will become tiger and helicopter parents. We will have our own prejudices.

The way forward is not to focus on the rivalry between generations. It has to do with understanding and moving beyond the stereotypes which divide and demonize us. Moving past such views can allow us to see each other as resources and move towards improvement and resolution of our shared concerns—to create an economically, socially and environmentally sustainable future that is equitable, inclusive and committed to the integrity of all.

This essay appears in print in the February 2020 issue of Maclean’s magazine with the headline, “Don’t you see yourself in us?” Subscribe to the monthly print magazine here.