No, it’s not ‘crazy’ to regulate emissions in the oil sands

The hit to oil sands development from the most commonly discussed greenhouse gas policies would be surprisingly small

Alberta’s tar sands are currently estimated to contain a crude bitumen resource of 315-billion barrels, with remaining established reserves of almost 174-billion barrels, thus ranking Canada’s oil resources as the second-largest in the world in terms of size. 119,4000 cubic-meters of synthetic crude oil per day were produced in 2006, with projections of that figure doubling within the next five years. The industry has brought wealth and sparked an economic boom in the region, but at a price. A new environmental disaster has been born, with contaminated fish and water filling area lakes. The Native-American tribes of the Mikisew, Cree, Dene and other smaller First Nations are seeing their natural habitat destroyed and are largely powerless to stop or slow down the rapid expansion of the oil sands development. ///

Share

As oil prices tumbled in the latter half of 2014, the Prime Minister and other Conservative Party MPs and cabinet ministers became fond of saying that, in these tough times, it would be crazy to implement meaningful greenhouse-gas policies in the oil sands. Of course, the Prime Minister has promised to regulate greenhouse-gas emissions from the oil sands directly or indirectly since his first term in office, when oil prices were about where they are today. They’ve been higher, lower, higher again, and now are back down, and still no regulations. With this post, the second of three as I prepare for testimony to the House of Commons finance committee on March 10, I’ll look at three questions. (Part one is here.) First, would introducing new, credible greenhouse-gas policies have a material impact on the prospects for oil-sands growth? Second, what properties of new policies are most important? And finally, is there really a magic bullet in using prices versus regulation? The answers, in my opinion, are: no, average cost, and no.

As oil prices tumbled in the latter half of 2014, the Prime Minister and other Conservative Party MPs and cabinet ministers became fond of saying that, in these tough times, it would be crazy to implement meaningful greenhouse-gas policies in the oil sands. Of course, the Prime Minister has promised to regulate greenhouse-gas emissions from the oil sands directly or indirectly since his first term in office, when oil prices were about where they are today. They’ve been higher, lower, higher again, and now are back down, and still no regulations. With this post, the second of three as I prepare for testimony to the House of Commons finance committee on March 10, I’ll look at three questions. (Part one is here.) First, would introducing new, credible greenhouse-gas policies have a material impact on the prospects for oil-sands growth? Second, what properties of new policies are most important? And finally, is there really a magic bullet in using prices versus regulation? The answers, in my opinion, are: no, average cost, and no.

Would new greenhouse-gas policies have a material impact on oil-sands development? They could, if they were extremely stringent and/or designed specifically to harm oil-sands activity. If neither of those is true, then oil sands will likely prove frustratingly resilient, at least to their opponents, to carbon pricing, or other greenhouse-gas policies implemented broadly in the economy. This is largely because the value derived per unit of emissions remains sufficiently high to justify the activity, even if those emissions are priced and, unlike some other industries, the oil-sands resource is not mobile. If firms want to extract the oil sands, they have to do it here. Sure, companies can look elsewhere for oil, but relocation is not as easy as it would be with, say, cement production.

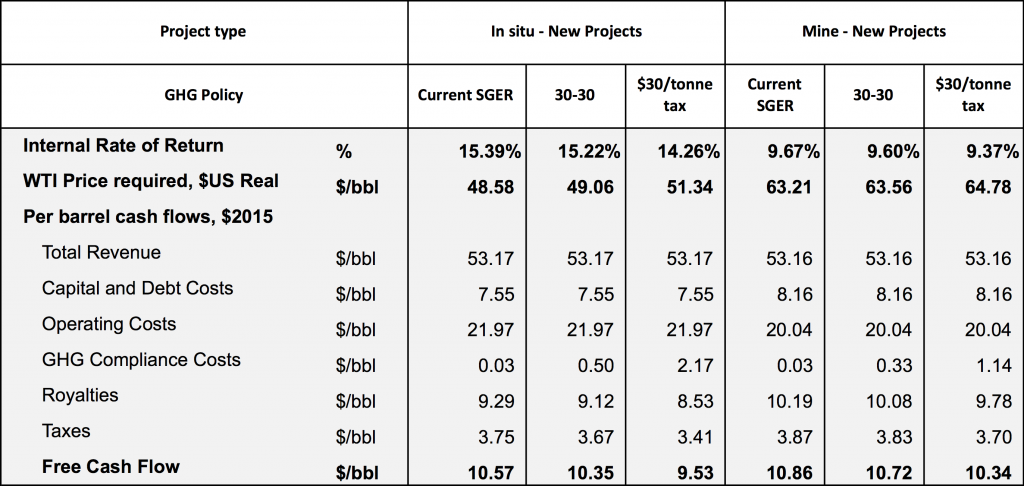

How big a hit would the types of policies most often discussed have on oil-sands-development prospects? You’ll likely be surprised. Consider here two policies: first, a modified version of the current Alberta Specified Gas Emitters Regulation, which would require either a 30 per cent reduction in emissions intensity or a payment of $30/tonne from oil-sands facilities (referred to as a 30-30 policy below). The requirement would be implemented gradually, reaching full stringency in 2020. The second is an application of a B.C.-style carbon tax, starting today, at $30/tonne. In both cases, the prices would be indexed to inflation, unlike the $15/tonne in the current Alberta policy, which has been fixed at that value since 2007. In the table below, I show the impacts of each of these policies on the returns to a new oil-sands project beginning construction today.

As you can see, the impacts are small but material, at least for the $30/tonne tax, relative to the current situation. All these numbers assume that the firms simply pay the tax, so these are worst-case-scenario figures. For an in situ project, the prospect of Alberta moving to a 30-30 approach would see average profits per barrel drop by $0.22, while moving to the tax that charges companies for every tonne of emissions would drop profits by a little over $1 per barrel on average, all in inflation-adjusted dollars. The impact on the project’s rate of return on investment is small, at 0.17 per cent for the 30-30 approach, but over one per cent for the carbon tax; the latter is certainly enough to be noticeable. The impact on the mines is smaller, as they have lower emissions intensity to begin with, but they have lower baseline rates of return, as well, so these smaller impacts could matter more. The B.C.-style carbon tax reduces profits per barrel from the mine by about 50 cents per barrel, while the 30-30 approach lowers profits by about 14 cents.

When the Prime Minister suggested that implementing greenhouse-gas policies in the oil sands would be crazy, the implication was that the policies would have a material impact on the development trajectory. For that to be the case, you have to believe one of two things: Either the resource is so marginal that it’s within a quarter per barrel of disaster, or resource companies are so opposed to ggreenhouse-gas policies, they’ll overreact to the small actual impacts and substantially reduce investment. Of course, there will always be marginal projects, and there will always be projects contemplated that don’t go ahead, and it’s likely these that worry the Prime Minister more than the health of the industry on the whole; he knows that a new greenhouse-gas policy would provide a convenient talking point for companies with projects already facing cancellation or a negative final investment decision.

The results above also show the importance of the design of the policies in understanding the impact on new oil-sands development. A carbon price sets the price at the margin—the cost of increasing or decreasing emissions by a small amount—but it may also determine the cost of introducing a new source of emissions into the economy, and set the average cost of operating an emissions-intensive industry over time. A carbon tax is a simple program: It charges you a fixed price for emissions whether old, new, high- or low-value, and economists like it for that reason, among others. A program such as Alberta’s, along with the EU emissions trading system, use free allocations of emissions rights to drive a wedge between the cost of increasing emissions and the cost of emissions on average. Under the EU’s system, industries must purchase some permits at auction, but many are allocated for free. Under the Alberta system, emissions rights are effectively allocated freely, as well, based on the history of the facility. The impact of a policy on the average costs of operations is what determines its impact on new investment and, in the table above, you can see the difference between the 30-30 program and the $30/tonne tax in this regard.

Finally, the results above are derived using carbon pricing, but that does not mean this is the only means to address greenhouse-gases in the oil sands, nor even the best way to do so. What?!? An economist saying carbon prices aren’t the best? Economics tells us clearly that carbon prices generate the most cost-effective emissions reductions by harnessing the power of the market (i.e., they get the most bang for the buck). What economics also tells you is that stringency matters as much, if not more, than cost-effectiveness in addressing the core problem: that the costs of emissions are not taken account of by those who pollute. The first-order problem for any economic policy is to correct that, and there is nothing in economics that suggests a weak carbon price will be better than a more stringent regulation. More than anything, we need a policy in the oil sands (and over the rest of the country) about which we can say that, if everyone else applied similar policies, we’d meet global greenhouse-gas-reduction goals. Whether this is achieved through carbon pricing or regulation is second order, but to ignore the primary problem would be, in the words of Prime Minister Stephen Harper, crazy.